What planet do our politicians live on? Labour’s video memorialising George Floyd, and pledging radical change to education and justice policies to combat the sort of ‘structural racism’ that led to his death, suggests which country. All this time I’ve believed I live in Britain, when in fact we’re all living in America.

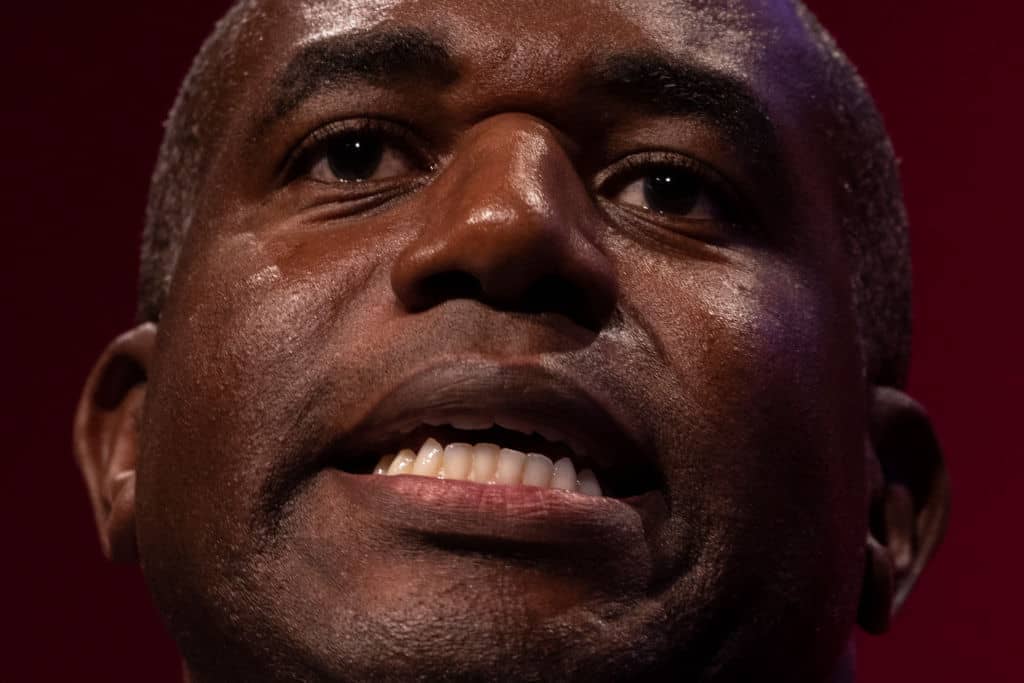

What other explanation could there be for a party pledging to radically reshape the nation based on events in Minneapolis two years ago? Why else would British politicians like David Lammy line up to say ‘he could have been me’? If we didn’t live in America, comparing a Harvard-educated London lawyer to a man living in a city on the other side of an ocean based on little more than the colour of their skin seems facile.

Why do protests leap from city to city? Because people identify with those protesting elsewhere. Why do they leap from country to country? Because we’re all Americans. Why else would trust among black British people in the police plummet when police in New York kill a man? British people watch American films and listen to American music. We use social media where Americans are by far the largest group of native English speakers. Is it any wonder we’re steeped in American political thought?

Why else would British politicians like David Lammy line up to say ‘he could have been me’?

This affliction is bipartisan: from Nick Timothy’s claim that ”being offensive’ is not an offence’’ to Ben Bradley’s belief that ‘we separated the church from the state a long time ago’, Conservatives are just as prone to spouting Washington cliches as their Labour opponents.

The big difference is that Labour’s theology means it tends to follow these cliches with action. If we live in America, we live in a racist society. And if we live in a racist society, we need to tear down structures until people are liberated. As always, this starts at school; people must be taught about black history, colonialism, and the slave trade until we ‘finally put an end to the structural racism’ that plagues Britain.

How exactly primary school history lessons help create this utopia is left unsaid by Labour. Cynics might note, however, that an education system which tells pupils their national wealth is the result of exploitation is likely to be one which produces voters more inclined towards the holy trinity of redistribution, foreign aid, and open borders.

Does this sound like a weak theory of change? If so, remember the most fundamental belief of modern progressives is that evidence of disparities is evidence of prejudice. If one group does poorly and another group does well, there must be something in the very DNA of the state that is oppressing the former.

The problem is that this doesn’t leave much room for nuanced explanations. It would be a curious sort of racism which causes Black African children to slightly outperform their White British peers, while Black Caribbean pupils lag far behind. Even this obscures detail; Francophone Africans perform significantly worse than Black Caribbean students. Is ‘structural racism’ really to blame for this?

You may at this point be tempted to conclude that importing American discourse on structural racism is unhelpful. You may believe that a country where the majority of the Black population consists of African families who arrived in the last 40 years seeking prosperity and opportunity differs from one where most Black people have family histories tracing back through centuries of slavery and segregation.

You may even be tempted to conclude that blaming ‘structural racism’ is a cop out that pretends to ask hard questions but leads to known and comfortable answers – more legislation, more education – rather than doing the hard work of providing the help communities need. If you are, stop. That’s hardly thinking in the spirit of Biden-Harris.

Comments