Death’s great paradox is its inconstant constancy. Its forms and rituals change from generation to generation. In our own era, antibiotics have reduced the chance of a fatal infection, and average life expectancy has risen to our eighties. Direct cremation means we can even ship Auntie Maudie, when her time comes, to the crematorium sight unseen and have her ashes returned via DHL. Our existential encounter with death in society is muted to a murmur.

Unlike the Irish and their open-coffin wakes, the English almost never now see a corpse. So it is hard to imagine how our great-great-grandparents lived in a world where fatal fevers struck at random and the infant mortality rate was 50 per cent. Or how the most minor accident – an undressed wound or a broken arm – could swiftly turn fatally gangrenous.

It is hard to imagine living in a world where the infant mortality rate is 50 per cent

For the Victorians, as Judith Flanders sometimes stomach-churningly shows in her splendid Rites of Passage, death was all around. Rivers stank with sewage; churchyards were stuffed with rotting corpses (it wasn’t until the middle of the 19th century that legislation sought to limit overcrowding burial sites) and streets were thronged with the spluttering, infectious poor. In the 1820s, a Revd Howse, intent on collecting burial fees, opened the cellar of his Baptist chapel near the Royal Courts of Justice in London’s Strand and, in the space of seven years, managed to cram 12,000 bodies into a plot the size of a small garden. The stench rose through the floorboards, mingling with hymns of resurrectional glory.

Above ground, typhus, cholera and tuberculosis raged, without their causes being understood. These diseases were still attributed to mysterious miasmas and ill balances of bodily humours. Laudanum was doled out as a pain suppressant. No one was immune, typhoid reputedly claiming Prince Albert in 1861 and very nearly his eldest son, the future Edward VII, ten years later.

But the Victorians readily embraced all this. The Rule and Exercises of Holy Dying, a sort of manual on the best deathbed routines, ran to 50 editions. The dying, surrounded by their loving kin, were expected to utter profound last words and be certain of their coming ascension into heaven. ‘A good death’ was deemed a vindication, or signifier, of a proper world order, albeit one built on vast economic inequality.

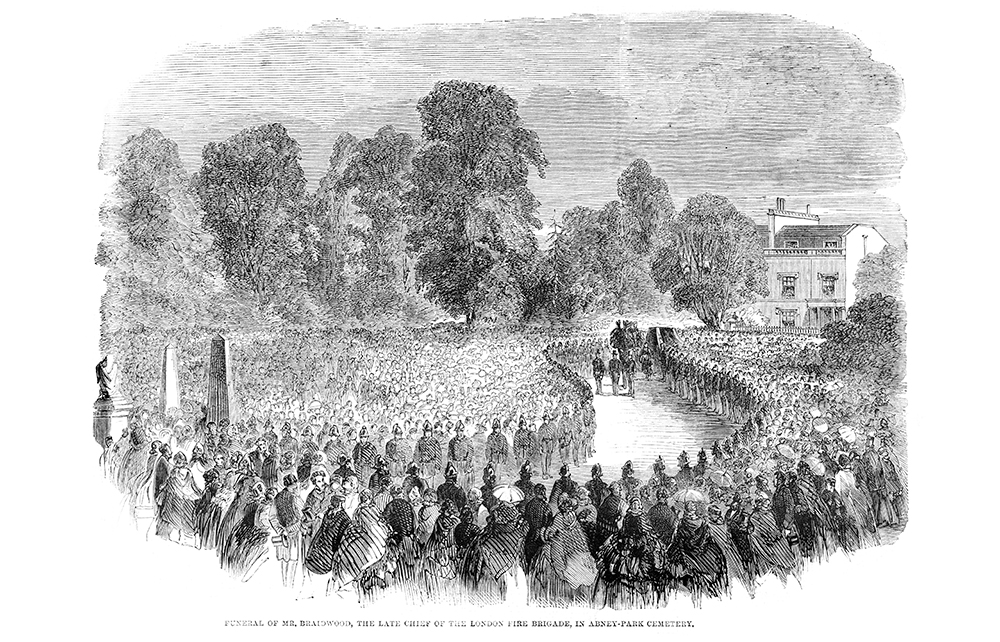

Victorian funerals were often extremely grand social events, with commemorative medals struck and the bereaved expected to wear elaborately codified mourning regalia for (in the case of widows) years afterwards. London’s Regent Street department stores even opened special ‘mitigated affliction’ sub-branches for those in half-mourning. Flanders paints a vivid picture of a society obsessed with the outward trappings of death and sorrow. To wear black crape on hats and dresses for an extended period became a mark of status.

What, in the end, did the Victorians do for death, and us? With their public health acts, fever hospitals, municipal cemeteries and Bazelgette’s sewers, they did eventually change the nature of death. The dying were removed out of the sight of the living and the dead were decently buried in what were then the leafy suburbs of Highgate and West Norwood.

Unknowingly, the Victorians also started to instigate the very process of separation between the dying and the living that now afflicts our own death anxieties – a neurotic avoidance of all talk of death and dying in polite conversation.

Random death from infection has diminished, and we are now shocked by infant mortality. But we no longer expect others to join with us in a long period of grieving. We have made sorrow private rather than public. Who now wears mourning aside from the day of the funeral?

Left unanswered in Flanders’s mesmerising work is whether the Victorians, despite their terrifying everyday mortal losses, were any better at negotiating death than us. Implicitly, it seems, we create the death etiquette we deserve and will receive. The Victorians made a big show, dressing in plain black for full mourning, followed by half- mourning in purple, mauve and grey. We remain kitted out in our casual daywear as if nothing of any significance has happened – and are then surprised when no one pays us much attention.

Comments