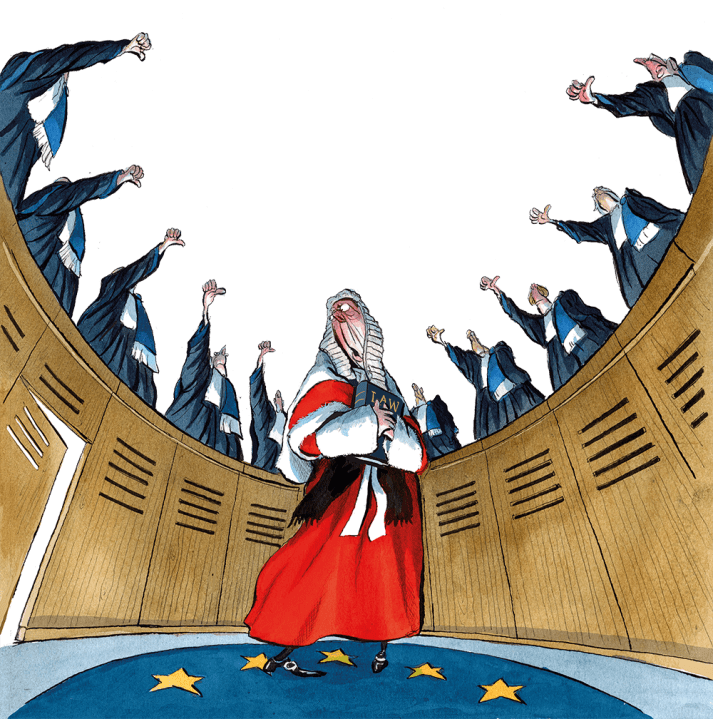

This year the European Convention on Human Rights and its Strasbourg court are 75 years old – the age at which British judges are obliged to retire. Is it time for Britain to retire from this ageing institution? Not according to the Attorney-General, Lord Hermer, a former human rights lawyer, who recently pledged that under Labour Britain would never leave.

Apologists for the ECHR invariably turn to myths to make their case, foremost of which is the creation myth. The ECHR, they say, was a British invention. It was inspired by Winston Churchill and drafted by David Maxwell Fyfe. It codified historic British rights and the UK was the first country to ratify it. A cynic may say that this appeal to national pride to justify a supranational body seems a tad rich coming from left-wing internationalists. More importantly, the story is false.

The truth is that Clement Attlee’s government ratified the Convention with reluctance and only on the basis that the European Court would have no jurisdiction in the UK, since British people would not be allowed to take cases to the court. They also decided to treat the Convention as non-binding and deliberately did not alter laws known to be incompatible with it. Moreover, when Churchill returned to No. 10 a few months later (with Maxwell Fyfe, now Lord Kilmuir, as his lord chancellor) they adopted the same position – as did subsequent Conservative prime ministers.

As for Churchill’s role, much is made of the fact that, in opposition, he endorsed the early proposal for a Court of Human Rights. But his other brief references to the court left it unclear whether he believed it would be just for west European countries emerging from fascism or if it would also apply to the UK. The ECHR’s mythmakers conveniently ignore the fact that when Churchill had the power to give the court jurisdiction in Britain, he did not do so. It wasn’t until 15 years later that Harold Wilson gave the Strasbourg court power to rule on British cases. He made the decision without informing parliament and with no publicity, as a singularly ill-judged attempt to join the European Community by showing British willingness to accept the jurisdiction of a supra-national court. Another Labour prime minister, Tony Blair, gave domestic courts the power to apply the Convention directly within the UK under the Human Rights Act.

There is a pretence that only right-wing extremists and constitutional pedants find the ECHR a problem

What about the claim that the ECHR simply codified British rights which had evolved over centuries? If that was true, our membership would confer little benefit; and few, if any, British laws or practices would be incompatible with the Convention.

If only. Judgments have been made in 567 cases concerning the UK, and our country has been found to be in violation in one or more respects in 329 of them. In addition, 25,647 British cases had been ‘decided’ by the court – the vast majority being declared inadmissible or rejected. Since the Human Rights Act, far fewer cases go to Strasbourg. Instead, many more cases involving human rights are heard by domestic courts. No record is kept of how many. However, in the Immigration and Asylum Tribunals alone, human rights cases were 40 per cent of the 350,000 cases received in the past eight years.

The ECHR’s advocates insist that the Human Rights Act does not give domestic courts power to override parliament. They can only make ‘statements of incompatibility’; it is for government to decide whether to ask parliament to keep, amend or repeal a law that’s deemed ‘incompatible’ with the ECHR. But that is at best a half-truth. In practice, governments can never retain ‘incompatible’ laws, since an appeal to the Strasbourg court (whose rulings Britain is treaty bound to implement) would inevitably uphold the domestic court’s ruling. Of the 47 declarations of incompatibility so far, 35 have resulted in parliament amending the law, and the remaining 12 have been overturned on appeal (which only shows how subjective they are). In a further 83 cases, British courts had to reinterpret legislation away from its original meaning to make it conform to the ECHR.

None of this would have been a surprise to those who warned Attlee’s government against accepting the jurisdiction of the court. His Lord Chancellor, Lord Jowitt, complained that the Convention ‘is so vague and woolly that it may mean almost anything’. That vagueness meant the court would have to invent new laws ‘compared to which the Code Napoléon – or indeed the Ten Commandments – are comparatively insignificant’. The Foreign Office’s legal adviser, Eric Beckett, echoed Lord Jowitt in his official briefing in 1950. The ECHR’s vagueness, he wrote, meant it ‘would be abused by pressure groups, provid[ing] a small paradise for some lawyers’.

How prescient such warnings were. The only thing that is certain about Convention rights is that they mean whatever Strasbourg judges decide they mean. Take even ‘the right to life’. That sounds pretty clear-cut. But when does life begin and how should it end? Suppose parliament passes the assisted dying bill, but the Strasbourg court then decides that the state cannot participate in taking life (a very plausible interpretation of that article). The court would prevail, parliament would be overruled and the bill would have to be annulled. Suppose the reverse happens and parliament rejects the bill. The Strasbourg court could rule, having declared the Convention to be a ‘living instrument’, that state-assisted dying is a human right. The court, accountable to no one, would prevail. Such scenarios show how power to make intrinsically political decisions has been transferred to unelected judges.

It was unrealistic to think that any authoritarian regime would be put off by a foreign court’s adverse rulings

If unaccountable judges are given power to tell parliament what laws it may or may not – or must – enact, then the judiciary inevitably becomes politicised. This undermines public respect for the rule of law itself. Demands for the political appointment and vetting of judges are already being voiced.

We do not want to end up like America, where Supreme Court judges are appointed on the basis of their political opinions and loyalties, as well as their actuarial life expectancy, so that the president who appoints them can determine legislation for decades ahead. Yet that future is almost inevitable if we stay in the ECHR.

The purpose of the European Court was not to fine-tune each country’s statute book but to protect fundamental freedoms which had been lost under fascism and communism. Yet even in that simple original objective the court has failed.

It was always unrealistic to think that any regime which was prepared to use torture, slavery or arbitrary arrest (for instance) would be put off by the prospect of adverse rulings by a foreign court. Whenever an authoritarian regime has come to power, adherence to the ECHR has not dissuaded it from trampling on human rights. In 1969, when the Greek colonels took power and faced an adverse ruling from the ECHR Commission about the use of torture, Greece withdrew from the Convention. Under Vladimir Putin, Russia revived many features of the Soviet regime while still adhering to the Convention, and was only expelled after its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, not for its rampant domestic human rights violations. Both Azerbaijan and Turkey have gone pretty far down the road to authoritarian regimes while remaining in the Convention.

The often-repeated claim that if Britain left it would be joining ‘Belarus and Russia’ is puerile. We would be joining other common law democracies – Australia, New Zealand and Canada – who uphold human rights without relying on a supranational court. If you were to listen to the court’s advocates, you would believe only right-wing extremists and constitutional pedants find the ECHR a problem. In fact, prime ministers and home secretaries of both parties – from Blair, Straw and Reid to Cameron, May and Sunak – have publicly considered resiling from the Convention in part or in whole, temporarily or permanently, or ignored its rulings. Even Keir Starmer recently criticised a judge’s ruling based on the ECHR (for which he was rebuked by the Lady Chief Justice). How will he react if his plan to impose VAT on private schools falls foul of Strasbourg?

To entrust lawmaking to a court that is accountable to no one was bound to be uncomfortable to British people. This conflict between parliamentary democracy and an unelected court is not a bug which can be fixed. In fact, it is a feature, not a bug. What makes the European Court a problem in Britain – its lack of democratic accountability – is precisely what appealed to its architects in the aftermath of Nazism and fascism. They wanted to create a constitutional check on democracy to prevent elected governments abusing their power. That was an understandable objective, but it has proved unrealistic and unjust.

Perhaps the most explicit example of the court’s disdain for democracy is its judgment against the Swiss government last year when it overruled the outcome of a referendum on climate targets. It declared: ‘Democracy cannot be reduced to the will of the majority of the electorate and elected representatives in disregard of the requirements of the rule of law.’ What voters want, in other words, is secondary to the opinions of Strasbourg judges.

Comments