The Wake, Paul Kingsnorth’s Booker-longlisted debut novel, was set just after the Norman Conquest, and was told in an odd hybrid of pseudo-Anglo-Saxon and modern English. Its narrator, Buccmaster of Holland, being displaced by the incoming Frenchies, gathered a group of fighters to resist, holding them together by the strength of his personality. But something more complicated is also going on: Buccmaster, prone to visions, was an unreliable narrator; reading the book was a shocking, difficult but rewarding experience, capturing a moment in time when a whole way of life was almost entirely destroyed.

Zoom forwards 1,000 years or so (the date is not specified) and we come to Beast, billed as the second part in a trilogy. Again our narrator, Edward Buckmaster, is a strong-willed man, bedevilled by things, internal and external, beyond his control. At first it seems he is a simple Luddite, seeking a saint-like experience: ‘I talked but never listened, I sold but never gave away.

Everywhere there were voices and I added my voice to them and we spoke out together and said nothing at all.’ He’s fled his family to a hovel on the moors; the reason for this is never made clear, but it seems to be a nervous breakdown, or perhaps even a terrible act of violence.

Although written in our tongue, the language is still relentless, even brutal; sentences run on jaggedly, commas and capitals vanishing as Edward’s mind deteriorates. Like his predecessor, he has strange dreams: ‘Distant lights out in the sea, fleets of swans flying, trees under water, old trees,’ but unlike Buccmaster he cannot pin them to anything specific, instead interpreting them as vague portents of ecological disaster, a world without humans, suffocated by vegetation. ‘Perhaps I am losing my mind. I do hope so.’ There is very little colour: everything is white, or shrouded in mist.

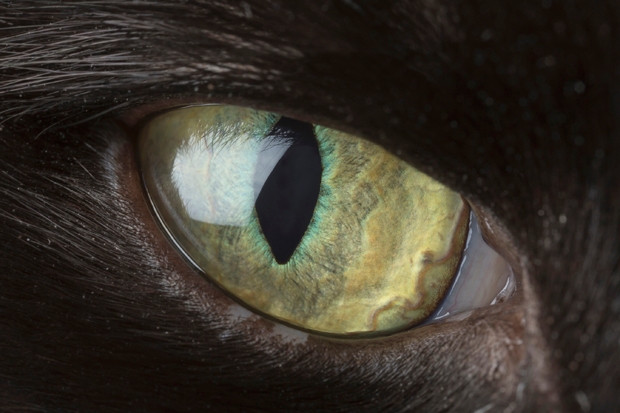

The beast of the title is a large, black, cat-like thing: Edward decides, though bruised and battered from a terrible fall, to follow it in order to grope for meaning. Too often, though, half-baked philosophy surfaces, and true revelation never appears.

Many basic questions (who buys Edward’s food, for example) are left

unanswered in this strange, elusive book, but it does have an undeniable power as a comment on the effect of new technologies. Who knew that England’s next defeat would be not by fire and sword, but by tweets and blogs?

Comments