On the morning of 31 January 1945, a private soldier in the United States army, a minor ex-con with a juvenile record for theft, called Eddie Slovik was put to death ‘by musketry’ for desertion at the village of Sainte Marie-aux-Mines in France. There had been no execution of an American soldier for desertion since the Civil War in 1865, but what made Slovik’s death so peculiar was that, in a war that had seen 50,000 American servicemen and 100,000 British desert, his was the only sentence that was carried out. Before his death he said:

They’re not shooting me for deserting; thousands of guys have done that. They just need to make an example out of somebody and I’m it … I used to steal things when I was a kid, and that’s what they’re shooting me for. They’re shooting me for the bread and chewing gum I stole when I was 12 years old.

Slovik was probably right — if you needed to shoot someone pour encourager les autres, an ex-con who had not so much as seen a battlefield must have seemed just about perfect. But the other odd thing about his execution was that it was carried out in secret. In the weeks before his death the military authorities convinced themselves that a stern example was needed to prevent mass desertions in the last bitter fighting of the war; but Eisenhower and the American command knew as well as the British government that the idea of shooting a young boy would have political implications on the home front and for troop morale that their armies simply could not afford.

The death penalty for desertion had been abolished in Britain by a Labour government in 1930; but by 1942 the problem in the Nile delta and the desert had become so grave that Auchinleck was pleading with London for its reimposition. From a military point of view the case for exemplary sentences convinced even the silkiest civil servant; and yet; like Eisenhower three years later, the British found themselves in a cleft stick, desperate to do something to stem the flood of desertions but unable to admit to Britain’s allies or to a British public fed on propaganda stories of the British Tommy’s heroism the humiliating scale of the problem they faced.

It was in this murky no-man’s-land between what the military authorities would have liked to do and what they were allowed to do that the extraordinary ‘desertion industry’ thrived; and it is this hideous landscape that Charles Glass explores in Deserter. A war that cost something like 50 million lives ought to put most human failures in perspective. But this is a world of frustrated and degrading brutality, racism and moral stupidity on the one hand, and of opportunistic greed, corruption, fear, mental disintegration and crime on the other, that makes most of the more familiar narratives of war seem uplifting by contrast.

‘The war was a criminal’s paradise, the most exciting and profitable time ever,’ one old ‘con’ recalled. ‘It broke my heart when Hitler surrendered’ — and across Europe and the Middle East deserters, thieves, profiteers and arms dealers breathed the same regretful sigh. At the end of the Napoleonic wars Europe was awash with more trained men than at any time since the end of the Roman empire, but that was nothing to 1945, when from Cairo to London and from Rome and Naples to Paris and Glasgow a vast pool of deserters and a seemingly limitless supply of stolen arms, made the good old days of Sir John Hawkwood seem like a Golden Age.

There were 20,000 deserters on the run and ready for pretty well anything in London, while in Paris the armed bands fighting street battles with Military Police and hijacking trains had turned the city into a ‘prohibition Chicago’. In Egypt a profitable line in gun-running was arming the Zionist gangs while in Rome they were in bed with the Mafia; and it is against this background that Glass interweaves his individual case studies.

For British readers the most familiar landscape will be that of the boxer-poet John Bain — Vernon Scannell — and the desert war. But the meat of the book comes with the stories of two Americans deserters: the brutal, bragging, whoring Paris gangster Al Whitehead, and Steve Weiss, the idealistic son of an introverted Great War veteran. Weiss had volunteered under age and fought bravely through Italy and France, only to end the war with a dishonourable discharge and a sentence to a lifetime of hard labour.

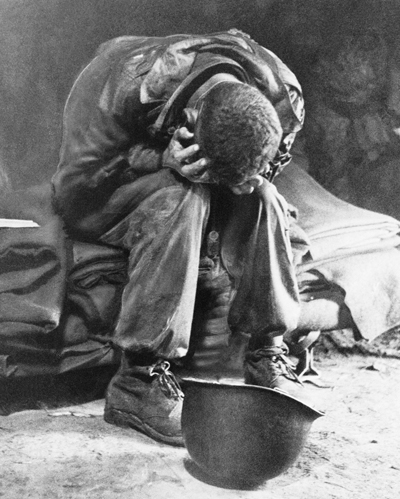

The world that he found himself in when he finally stumbled away from the battlefield, unable to bear it any longer, was a world of sadism, uncomprehending authority and institutional injustice that makes for shameful reading. Weiss is still alive, and has co-operated in this book, but if Glass makes little attempt at neutrality few readers will mind that. Like Bain, who was imprisoned in the vile Mustafa Detention Barracks in Egypt, he had sunk into a world stripped of all humanity. It is a world in which systematic cruelty is the order of the day, an isolated, secret world in which the whole machinery of military discipline, designed to turn the individual into a fighting unit, is bent instead into an instrument of revenge against men who it cannot shoot and can no longer use.

‘The second world war,’ Glass writes slightly bathetically, ‘was not as wonderful as its depiction in some films and adventure tales’; and for those with the stomach for it, here, powerfully, is chapter and verse. The enduring gallantry of the ordinary Tommy? The bond between the junior officer and his men? The cheerful profanities of the Glaswegian Jock? The romance of the French Resistance? The innate moral superiority of the democracies? The chivalry of the battlefield? If you have tears, prepare to shed them now.

Comments