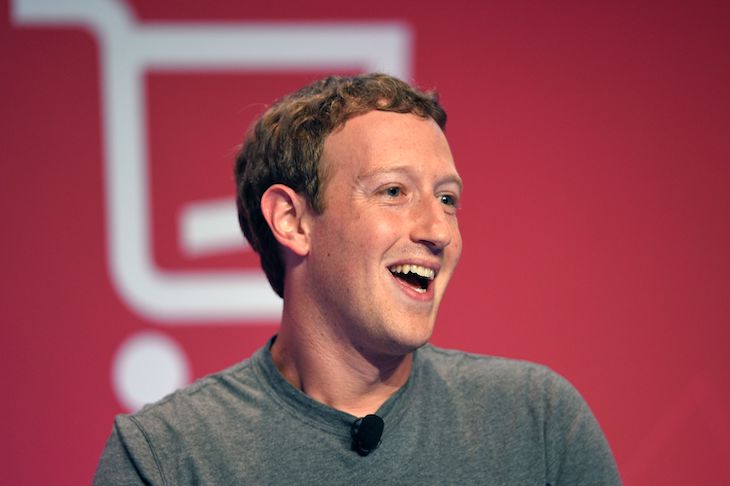

Mark Zuckerberg says that Facebook could be to its users what churches are to congregations: it could help them feel part of ‘a more connected world’. That got a dusty response. Facebook as church, eh? So the man who helped an entire generation to replace real friends with virtual ones and online communities is sounding off about people feeling unconnected? Cause and effect or what?

He wasn’t quite touting Facebook as an alternative church. It is, rather, now using artificial intelligence to suggest groups that its users might join — anything from locksmiths’ societies to addiction groups and Baptist organisations — and Mr Zuckerberg is enthusing about the benefits of moving from online to offline groups: ‘People who go to church are more likely to volunteer and give to charity — not just because they’re religious, but because they’re part of a community.’ So he’s trying to get more people to join things. Only — only! — 100 million of Facebook’s two billion users belong to a group that gives them a sense of community; he wants to raise that to a billion.

He’s right, obviously, about the benefits of being part of a group, from bellringers to Free Presbyterians, though it’s a bit weird for him to be evangelising for something that already exists, something that you might say is part of the human condition, given that we’re social animals. To take the most basic example, churches and parishes are ready-made communities under the noses of all of us. Just as they’re in radical decline in developed countries, Mark Zuckerberg is talking about how good it is to have a pastor looking out for your wellbeing.

But it’s interesting that Zuckerberg identified the function of a church, specifically, as something that needs replicating. Churches were once the most obvious centre of any community, and at times of crisis, like after the Grenfell Tower fire, people still congregate there. But what’s now evident is that churches have other benefits. Specifically, churchgoing seems to have a bearing on the very contemporary problem of mental health. The object of going to church isn’t mental wellbeing, but it happens to be a documented side-product of ‘doing’ religion. And I don’t mean in the Alastair Campbell sense. A persistent finding in the field of mental health research for some years is that there is a beneficial effect of church attendance; religious practice, per se. It’s not about affiliation or spirituality, but about actually going to church. Including, I suppose, going to church all by yourself.

Plainly, it isn’t an infallible route to mental wellbeing. At Easter the Archbishop of Canterbury’s daughter talked about her depression, notwithstanding her father being a bishop, and observed that in some evangelical bits of the Anglican communion, fellow Christians may unhelpfully attribute your illness to demonic possession.

But overall, the research suggesting a link between better mental health and active religious engagement of some sort or other is a sizeable one. One study published at the end of last year in the Journal of Religion and Health reviewed 74 studies in English and Arabic between 2000 and 2012 and concluded there was ‘a significant connection between religious belief and practices and mental health’. Note the ‘practice’ bit, which is true for Jews or Muslims, too. And in January of this year there was a study in the Journal of Nervous and Mental Disorders from the department of psychiatry at Yale Medical School. It says that ‘ample literature supports the protective effects of religious affiliation on suicide rates’. It goes on to observe ‘the mechanisms for this protective effect include enhanced social network and social integration, the degree of religious commitment and the degree to which a particular religion disapproves of suicide’.

It’s not simple or infallible: there’s another small contradictory study suggesting that religious affiliation could be a mental health risk factor in some cases. Overall, however, the evidence suggests that religion helps.

At its simplest, going to church is a way of being communal, and as Mark Zuckerberg points out, lots of us aren’t nowadays. A Sunday service means you get to see people and it involves simple routine, but being in a parish can also include taking the collection, helping out at a food bank, doing the church cleaning, whatever. That brings us back to the Facebook approach: anything that makes you part of a bigger group and a bigger picture is all to the good.

A friend of mine, Patricia Casey, professor of psychiatry at University College Dublin, is doing research into depression and religiousness: and she too says that ‘in virtually all the studies, spirituality as distinct from religious practice fares less well when it comes to mental health’. It’s interesting because for a long time secularists have tried to portray religious belief as a form of mental illness, yet the evidence suggests it might be the cure.

What the findings show, says Patricia, is that ‘even if you control for the social support, religious attendance is still significantly associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms’. In other words, although being part of any group (well, within reason — not Isis or paedophile networks) is good for us, religious practice and churchgoing have benefits beyond other kinds of association. ‘Our findings suggest that the social support associated with religious practice is likely to be qualitatively different from the social support of having friends in a football club or knitting circle,’ says Patricia. If you believe in spiritual life, it’s not that surprising: you’re communing with God here, not just other people.

Which isn’t to say we don’t get mental health and social benefits from all sorts of things, from knitting to football; there’s a well-documented association between health and contact with nature, for instance.

When it comes to community, Mark Zuckerberg is right about the merits of going from online to offline. But churches have been providing all this stuff for ever: it’s odd, not to say, irritating, that Facebook is discovering their merits just as they are going out of fashion.

Comments