Does being gay make you a better historian? ‘Immensely, immensely,’ says Diarmaid MacCulloch. ‘From a young age, four or five onwards, I began to realise that the world was not as it pretends to be, there are lots of other things there. You learn how to listen to what is being half-said or implied, and that’s a transferable skill.’

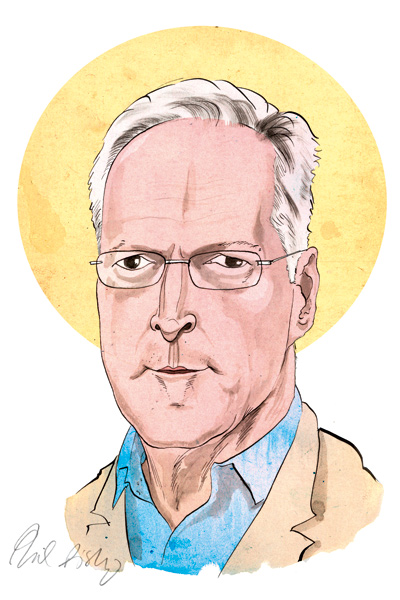

MacCulloch knows what he’s talking about. He’s Professor of the History of the Church at Oxford and one of Britain’s most distinguished living historians. In academic terms, he’s on a par with David Starkey, who also happens to be gay. Like Starkey, MacCulloch is a Tudor specialist who has branched into other areas and television work. In 2010, he produced A History of Christianity: The First 3,000 Years, a 1,200-pager that was turned into a well-received BBC series.

His new book, Silence: A Christian History, is a more esoteric project. MacCulloch connects silence to all his most profound interests: history, theology, literature — even music. ‘Silence is allied to wordlessness and wordlessness is allied to music,’ he explains in the book. He refers to ‘the dog that did not bark in the nighttime’ in Conan Doyle’s ‘Silver Blaze’. (The animal’s quietness suggests to Sherlock Holmes that it knew the killer.) For MacCulloch, the good historian must do his own detective work and read into the gaps, listen for voices that weren’t recorded. ‘History has been written largely by men and the noise in history is mostly male,’ he says. ‘Subtract that, and you can hear all the other voices which haven’t been heard — most obviously, and crudely, women.’

Er, sure. But how do you interpret silence, really? You can read sources for things that might have been left unsaid, but that is inevitably a subjective process. Isn’t the historian of silence free to read whatever he wants into his subject? ‘Yes, but you need to see that silence is never silence,’ replies MacCulloch. ‘There’s no such thing as a vacuum in this created world. You can hear what is in silence if you shut your ears and try to listen above it.’

That still sounds rather waffly, especially coming from such a robust historian as MacCulloch, who attacks other academics for their biases and says he has ‘nothing but contempt’ for post-modernism. What is he really trying to say?

The clue, Watson, is in that word ‘created’. MacCulloch is a believer. For him, as for most Christians, divinity and silence are entwined. God is silent and invisible, even to those who want to hear and see Him. But He is there. ‘The essence of the authority of God is its thereness,’ he says. ‘It’s a bit like our relationship with our parents. There is nothing you can do about it. You can’t declare someone else to be your dad. That seems to me to be a statement about religion. I have a relationship with the Bible because it’s just there. I may not like what it says, I may not approve of it or obey it, but it’s there and I’ve got to cope with it.’ In Silence, he’s trying a synthesis of history and theology — he is attempting to edit out the man-made noise of the past and tune in to what he calls ‘the Divine Wild Track’.

MacCulloch’s relationship with God is complicated. The only child of a country parson, he grew up lonely and alienated in a big rectory in Suffolk. He loved his parents, but was angry about Christian homophobia. Now 61, he seems to have been reconciled to the Church of England. He’s a deacon and speaks fondly of Rowan Williams and Justin Welby, but he wants to push the leadership of the Anglican Communion towards embracing gay marriage. He is an avid hater of clericalism. Yet every Sunday he celebrates the high-Anglican liturgy at St Barnabas’s in Oxford. ‘I go for orthopraxy — the form — not orthodoxy,’ he explains.

He says that he has ‘moved steadily leftwards, like Mr Gladstone’, and there is something Gladstonian about his moral earnestness. ‘History cannot be value-free,’ he says, with a serious face. ‘We should feel ashamed of something like the Holocaust. And we should blame someone or something if we see evil. Our profession is not a revolutionary profession but it is a subversive one: we are always subversive of smugness and stupidity and lies and power.’

MacCulloch isn’t terribly subversive about his own ideas. His values are of his time. He thinks religious dogma on sex should be confined to the history books. He is contemptuous of the hierarchy of the Catholic Church. Roman Catholicism made a big mistake with its move towards papal infallibility in the 19th century, he says. ‘It turned away from its natural state of diffused authority. The Roman Church seems to have forgotten in the last 150 years that it has all these other traditions and now they’re there waiting for the church in its hour of crisis. The last two papacies have been disastrous — nemesis has got them now.

‘Conservative Catholic friends of mine are increasingly disappointed and angry,’ he adds, referring to recent Vatican scandals. ‘These people are suddenly confronted with realities, and they are unwilling to defend the hierarchy in the way that they used to. It’s lovely seeing that sort of attitude emerge. It’s nothing but healthy for the Roman Catholic church. It is a sort of Anglicanism -emerging.’

MacCulloch insists that he is ‘not anti-Catholic, but anti-curial’ — though it’s easy to see why he has a reputation for being the former. He seems a bit too gleeful about the Vatican’s problems, and unwilling to acknowledge that, for many left-footers, the picture is not so gloomy.

As a historian, much of his energy has been spent countering Catholic revisionism. He recently had a public clash with his ‘old friend’ Eamon Duffy, whom he accused of being ‘a Catholic historian rather than a historian who is Catholic’. The revisionists have done a useful job, he says, of dismantling the Protestant myth of reformation. ‘But it’s in danger of becoming an orthodoxy, just as the old Anglican picture was.’

Nevertheless, it seems odd that someone who puts such a stress on historical objectivity should come down so consistently against the Church of Rome. His next book — ‘the literal bookend of my career’ — is a huge volume on Thomas Cromwell, the man who presided over the dissolution of the monasteries. Like the novelist Hilary Mantel, who says that ‘nowadays the Catholic Church is not an institution for respectable people’, MacCulloch sees Cromwell as a sympathetic figure. He describes Cromwell as a ‘self-contained idealist who wanted to shape the kingdom of England in the name of a new religion’. Might something similar be said of Diarmaid MacCulloch?

Comments