I’m writing this from a hotel room in Stockholm where I’ve been stranded for the last 24 hours thanks to bad weather. Turns out the Swedish airport authorities aren’t any better at coping with snow than ours — which is surprising given how often it must snow over here. Nevertheless, it has given me an opportunity to reflect on why David Cameron hasn’t been more assiduous about following in the footsteps of Fredrik Reinfeldt, the leader of Sweden’s centre-right coalition. I think the answer has something to do with the works of Charles Dickens, particularly A Christmas Carol.

Sweden’s recent economic success — it recorded the strongest growth in the EU last year — has been chalked up to ‘the Swedish model’, whereby a significant percentage of public services are delivered by commercial providers. Reinfeldt and his pony-tailed finance minister Anders Borg have been more successful at cutting public expenditure than their British counterparts thanks to the efficiency savings this model has produced. Put simply, Swedish private companies have been able to deliver more for less.

British politicians of all stripes have embraced ‘the Swedish model’ (no jokes please), but the ‘marketisation’ of our public services has been happening very slowly nevertheless. For instance, Michael Gove has yet to allow for-profit companies to set up free schools, something that’s been possible in Sweden since 1992. This cautiousness has meant that only a modest number of free schools have been set up in England since 2010.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I’m not criticising Gove for being too timid. Nor do I blame Nick Clegg for slamming the brakes on. Rather, I think the leaders of all the political parties have calculated that rolling out ‘the Swedish model’ too quickly would be politically imprudent. (Even Ukip is committed to ‘safeguarding’ the NHS.) And they’re probably right. A majority of the British public just isn’t ready to see large parts of our welfare state administered by private companies.

One reason is they don’t have much confidence in the ability of commercial providers to do a better job than the state — which is understandable, given how patchy their record is. (Did I hear someone say ‘Southern Cross’?) But this suspicion isn’t based on a forensic, evidence-based analysis. Rather, it’s rooted in a fundamental mistrust of businessmen. Most people worry that commercial providers will cut public services to the bone, regardless of the human cost.

Which is where Dickens comes in. In virtually all of his books, from Great Expectations to Hard Times, capitalists are depicted as mean and heartless — men whose humanity has been eaten away by their relentless desire to make money. Ebenezer Scrooge is a case in point. When the Ghost of Christmas Past takes him back to his youth, we see Scrooge actively choose his love of gold over his love of Belle, a beautiful young woman.

It’s not just Dickens. We see the same unsympathetic portrayals of capitalists occurring again and again in the English literary canon. The mill owners and moneylenders are contrasted unfavourably with the labouring poor, who are usually depicted as noble savages, and the land-owning aristocracy, who are paternalistic, one-nation Tories. They are loathed by the working class for being rich and looked down on by the upper class for being in trade. They are the antithesis of everything that is honourable and romantic in the British character.

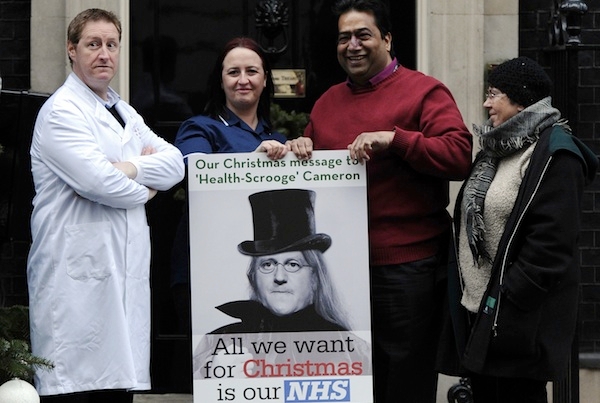

Danny Boyle relied heavily on this Dickensian caricature of industrialists in the Olympics opening ceremony and, in his version of history, the welfare state emerged to mop up after them and keep them in check. This was thanks to the heroic efforts of the trade unions, according to Boyle, and the emotional climax of his extravaganza was a lachrymose celebration of the NHS. It was easy to be irritated by all this — I described the opening ceremony on Twitter as ‘a £27 million party political broadcast for the Labour party’ and got it in the neck as a result — but we should be grateful to Boyle for spelling out so explicitly the connection between mistrust of the profit motive and faith in the welfare state. It was good versus evil in Boyle’s universe, and he was probably articulating the prejudices of millions.

So that’s why ‘the Swedish model’ has been so slow to take off in the UK and why poor George Osborne has had to abandon his deficit reduction targets. For complicated cultural reasons, connected to our wretched class system, reform of our hopelessly inefficient public services will continue to pro

Comments