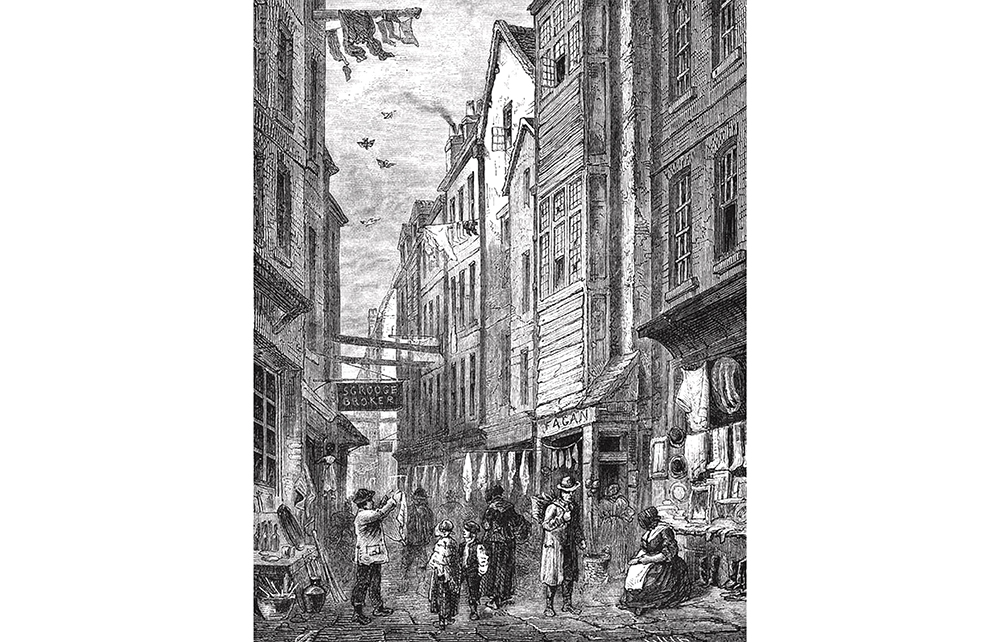

Is Dickens’s London a place, or a state of mind, or a bit of both? I used to ask myself the question all the time when I was literary editor of this periodical and our office in Doughty Street was a few doors down from the Dickens Museum, at no. 48, the house where he lived in the early days of his fame and where his beloved sister-in-law Mary Hogarth died. The deputy lit ed, Clare Asquith, and I used to walk in those days before computers to the press, which was in Saffron Hill, Clerkenwell, the scene of Fagin’s lair. We’d pass Bleeding Heart Yard, where so much of Little Dorrit takes place. Many of the streets near our office – Brownlow Street, for example – took their names from characters in Dickens’s novels. But which came first: Dickens or the place names? Was Bleeding Heart Yard so named because of the novel, or did he use this highly evocative place name because it was already there?

Dickens would sit on Old London Bridge waiting for the Marshalsea to open so that he could visit his parents

I did not find as many answers as I’d hoped from reading Lee Jackson’s book on Dickensian London. The city changes, of course, at a prodigious rate. The Victorians destroyed more Wren churches than did the Luftwaffe, and Dickens’s life (1812-70) saw the destruction of many of his haunts. We remember the opening passage of Dombey and Son, with its evocations of the gouging out of Camden Town to make room for the railways.

The White Hart Inn in the Borough, so vividly described in The Pickwick Papers, was demolished in 1889. There’s a haunting photograph of it in the book. The galleries where Mr Jingle and Miss Wardle dodged the pursuit of the Pickwick Club had by then been turned into cheap slum apartments. The Fleet Prison, where Mr Pickwick was incarcerated for breach of promise and where Sam Weller commiserated with a caged bird (one of the most beautiful passages in all English literature), was closed in 1842.

Jackson has a vivid chapter on Old London Bridge. David Copperfield tells us:

I was often up at six o’clock. My favourite lounging place was old London Bridge where I was wont to sit in one of the stone recesses, watching the people going by, or I looked over the balustrades at the sun shining in the water, and lighting up the golden flame on the top of the Monument. The Orfling met me here sometimes, to be told some astonishing fictions respecting the wharves and the Tower; of which I can say no more than that I hope I believed them myself.

It was here, in other words, that Dickens began his childish habit of fictionalising London. It is here at the bottom of the stairs that Nancy met Mr Brownlow and Rose Maylie to tell them the truth about Oliver Twist, thereby sealing her own fate, since Sikes will murder her for blabbing. Strangely, a blue plaque near the modern steps of the new (1962-73) London Bridge tells the unwary that this was where Nancy was murdered, whereas readers of the book will remember her being clubbed to death indoors. Jackson makes a strong case for the power of Old London Bridge over Dickens’s youthful imagination, since it was here that he sat and waited for the Marshalsea prison to open in the mornings, so that he could nip in to see his parents, incarcerated there for debt. Jackson assumes we’ll know where the Marshalsea was, but some readers would have liked to be told.

Other readers’ hearts might sink a little when they learn that this book started life as a PhD thesis for the City University, formerly Royal Holloway. But I felt that Jackson had knocked the academic dissertation into more or less readable shape, even though not always making clear what the subject was. Is it about Dickens tourism – guided tours of Dickens’s London, souvenirs, etc. Or is it about the fascination of London itself, which the reading of any Dickens novel will awaken? Or both? Most of us will remember, the first time we read Bleak House, wondering where the graveyard is, where Little Jo the Crossing Sweeper takes Lady Dedlock to visit the grave of her lover. I can recall my schoolboy excitement in Lincoln’s Inn Fields when I saw the original Old Curiosity Shop. As Jackson informs us, this establishment has no connection with Dickens and was a simple, clever invention by a shopkeeper who wanted to cash in on the legendary name. I still feel excited when I pass it, which shows that when one is looking for ‘Dickens’s London’ it is not for a mere piece of topography that one has been searching. Like the Empress Helena finding the True Cross, one is walking in an imaginative world.

Together with the fogs which engulf the Court of Chancery or the detritus and corpses floating on the surface of the Thames, or the busy river traffic, through which Pip and Magwitch make their failed escape, much of Dickens’s London can no longer be seen with the bodily eye. But it remains more vivid than the concrete skyline which we view from the windows of the bus. I suppose this was Jackson’s real theme, and I enjoyed his book, even though it’s a bit of a hotchpotch, hopping from theme to theme and not really having a narrative.

Comments