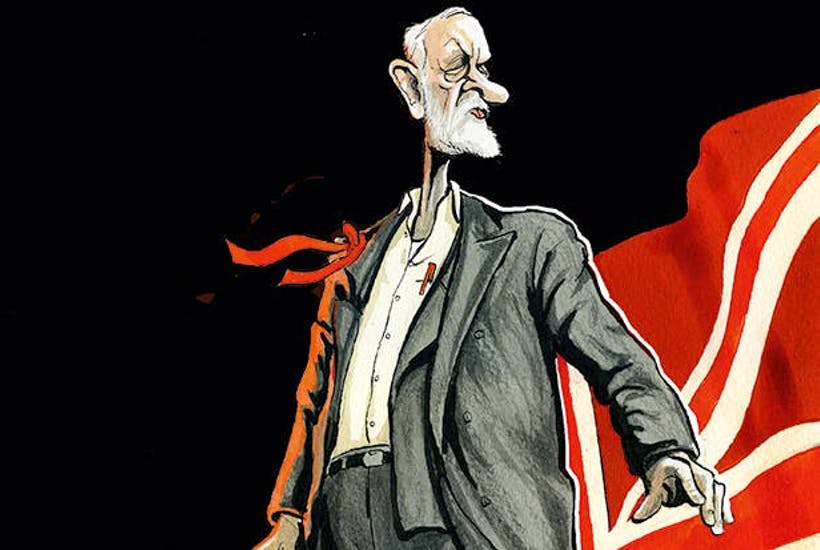

There are two competing theories about how the Soviet Union collapsed. One holds that Ronald Reagan’s moral leadership against communism and bolstering of US defences weakened Moscow’s will and buried them economically. The other contends that Mikhail Gorbachev’s domestic reforms and wise diplomacy brought down the Iron Curtain in spite of the cowboy in the White House. We can now add a third hypothesis: Jeremy Corbyn did it.

If the claims of a former Czechoslovakian agent are to be believed, the Labour leader was a paid informant for the secret police. That would certainly explain the devastating collapse of state socialism. Even the mighty Warsaw Pact could not have withstood the support of Jeremy Corbyn.

Corbyn denies the allegations and can pray in aid two compelling points. One, he has spent his life championing every miserable stupidity to pass as a doctrine of human affairs. Communism was notoriously inefficient but not so much that it would have paid Corbyn to do something he would surely have done for free. Two, the Czechoslovakian spooks could have learned more about British intelligence from watching a Bond movie than from receiving cables from Corbyn. And not one of the good Bond movies. One of the Timothy Dalton ones.

The Soviets managed to turn Kim Philby, Alger Hiss and the Rosenbergs. The idea they would then focus their energies on a crank marrow-grower from north London is dubious. What possible intelligence could he have provided them? Advance notice of his early day motions on Israeli settlements? Gossip from the annual Troops Out fundraising tombola? The ŠtB (the Czechoslovakian secret police) was notorious for its cunning, cruelty and ruthlessness, a reputation one does not gain by deploying the understudy Tony Benn on reconnaissance missions. If Jeremy Corbyn had been a spy for the Eastern Bloc, the Lives of Others would have been a comedy.

None of this matters a great deal. Whether you believe the more lurid claims about Corbyn or you reckon, as I do, that he was an occasionally useful idiot, you won’t have failed to notice the lacklustre reception given these headlines. That the man who could be Britain’s next prime minister may, at the very least, have sympathised with totalitarianism ought to be on every set of lips in the land. It ought to disqualify Corbyn from public office and polite society.

It does not because we do not view communism with the horror accorded to other types of tyranny. History may be written by the victors but they often leave it up to their academics, and in this the evil empire has benefited from a sensitive burial by friends and warm acquaintances. An overeducated generation, born on communism’s death watch, is largely ignorant about events only a few decades gone. A 2016 study commissioned by the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation discovered that 42 per cent of millennials were unfamiliar with Mao Zedong, one-third thought more people were killed under George W Bush than Stalin, and 80 per cent underestimated communism’s death toll.

Communism was always adept at exploiting regional grievances and appearing to side with the oppressed of the non-communist world. It was this feigned humanitarianism that attracted so many otherwise progressive people to this most reactionary of ideologies. In co-opting the early stirrings of various worker, liberation and egalitarian movements, communism benefited (and still does) from an imaginary benevolence. Communism has good intentions; it hates the right kind of people. In truth, it is a philosophy of oppression, an impulse towards mechanised misanthropy. Communism shot, hanged, tortured, enslaved, ethnically cleansed, purged, starved, imprisoned, exploited, crushed, burned, invaded, occupied, and collaborated its way through the 20th century. In North Korea and Cuba its pall lingers still.

Is ignorance paving the way for a revival of communism? As a political programme, no. The populist mush which has displaced pragmatic, reforming social democracy in some centre-left political parties does not represent communism in any meaningful sense. (Or, for that matter, socialism.) What accompanies it, though, is an attitudinal communism that expresses its leftism in denunciations of dissent, purges of internal rivals, violence and threats of violence, dehumanising language, and attacks on ‘liberals’ and ‘Zionists’. Allied to this is Lolshevism, a semi-ironic affectation in which the speaker breezily extols communism or adopts its rhetoric or symbols. The tone is glib, allowing a plea of humour should they be confronted, but there is an underlying solemnity. This trivialisation did not begin with millennials, many of whom would struggle to identify the beret-sporting mass murderer on their parents’ favourite undergrad T-shirts. It is, nonetheless, a cold and base form of politics.

Comments