Last time I looked, my online petition was not generating the support I had expected. You can find it on Facebook and it is entitled ‘Everybody Should Be Sacked or Killed.’ Only 38 people have so far pledged their support for this laudable proposition, which is way short of the number that would enable my bill to be debated in parliament.

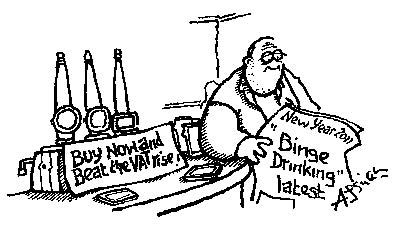

The problem, I think, is not the substance of the proposal, but my own technological inadequacies. I do not know how to download an image, a feat which is required if I am to advertise my proposition to the millions of people who use Facebook (worth £50 billion apparently) — so the only people who know that the petition is out there are those few who were Facebook friends of mine in March last year, about 150 decent souls in all. I wonder how many other great ideas have been stymied for the most trivial of reasons, how many luxury ocean-going liners with five swimming pools and after-dinner speeches by Ann Widdecombe have been ruined for a ha’porth of tar.

I had thought my proposal captured the essence of this new democratic medium, sort of summed up the aspirations of the internet-savvy population. An expression of inchoate rage, spite and nihilism directed at whoever the hell you wanted it to be directed at — racists, blacks, politicians, bankers, lawyers, comedians, social workers, mathematicians and carpenters’ wives. For the minority of internet users who do not spend their entire time online watching Ukrainian women servicing farmyard animals, most of the energy seems to be expended on monomaniacal vindictiveness and fury.

There is something about the immediacy of the internet that predisposes people to rage and vengeance, which facilitates splenetic denunciations and demands for peremptory punishment; there is little that is measured, thoughtful or humane out there. Everybody should be sacked or killed, or both. It is like a gigantic version of the famous Milgram experiment from the 1950s, where members of the public cheerfully applied electric shocks to other human beings when they answered a question incorrectly.

The Milgram experiment was supposed to show our susceptibility to authority under certain conditions, the depths to which we will stoop when told it is OK to do so by important-looking men in white coats. But the internet suggests you don’t even need the men in white coats to unleash the stooping; the world wide web comprises a community which, for the most part, is proud and happy in its utter certitude and rectitude and demanding of immediate and brutal redress for those who disagree. For whining liberals like me it is a bit of a paradox, a little like Saudi Arabia: we may loathe the corrupt and authoritarian House of Saud, but hell, compared with the average man on the street in Riyadh or Medina, the views of the rulers are comparatively egalitarian, enlightened and civilised. So it is, it would seem, with the rest of us.

Luckily Britain is not about to embrace this vision of Total Democracy, despite the announcements from the government in the last week. It has been said that online petitions may soon be debated in parliament, via the Directgov website — and some MPs, such as the eminently sensible Paul Flynn (Labour) have raised objections.

Paul should not be too worried; the system will ensure that no difficult stuff ever gets to parliament. The last government allowed for petitions to be sent via the internet to Downing Street, but struck out all of those it thought might frighten the horses. You would suspect that the present government will do precisely the same. Look down the list of now-closed petitions allowed by the last government and the frontrunners are almost all examples of worthy, piddling and uncontroversial minutiae: allow the Red Arrows to fly past at the Olympics; create a new public holiday to remember the Fallen; build a special hospital for members of the armed forces and so on.

There are one or two about fuel prices and the building of a super-mosque in London which might genuinely excite public debate. But for the real controversies you have to go to the list of petitions which the government, for no possible rational reason that I can understand, save for distaste — disallowed. Should we charge migrant workers for the care and education of their children? Should the statue of Nelson Mandela in parliament square be replaced by a statue of someone who has, at some point, however fleetingly, had something to do with this country? Should there be a ban on Scientology recruitment centres? Should we outlaw the ‘cruel and medieval’ practice of female circumcision?

My answer to at least three of these is a resounding ‘yes!’ and I’m ambivalent about the fourth — but, for reasons which have within them no logic or reason, they were deemed to transgress the parameters of such petitions and, therefore, were outlawed. So the government’s plans for direct democracy, through its Directgov website, will indeed be direct democracy, but only for issues about which the government is either bored rigid, simply uninterested, or with which it is in tacit agreement. Everything else will be disallowed on the grounds that it is ‘offensive’ or ‘provocative’ or ‘party political’. It is a little like those progressive state schools which encouraged their pupils to elect democratically accountable school councils but then decided that they should have dominion only over stuff like whether or not the snack bar should be open at break times, rather than things like whether or not all lessons should be abolished and Mr Fiddler, the PE teacher, reported to Childline. For which I suppose we should be grateful.

Comments