The Expansion Project, Ben Pester’s debut novel, builds on the satire of corporate culture that he previously explored in his short stories. It centres on Capmeadow, a business park that proliferates with offices, wellness gardens, chalets, convenience stores and even a temple carved with reliefs of ‘collaborative working practices’. Shrouded in creepy mists, it seems to ‘reproduce itself’ with a will of its own, like ‘a -living community fabric’.

Tom Crowley, who writes briefs for fire safety protocol, endures a stressful journey taking his eight-year-old daughter, Hen, to his office, mistakenly believing that it is ‘Bring Your Daughter to Work’ day. She seemingly goes missing. But then Tom is shown CCTV footage which suggests she was never there at all. Even when he learns she is safe at home he never stops looking for her, the sense of loss and panic that has taken root inside him escalating daily.

The bewilderment and alienation that Tom suffers permeate the Capmeadow park. In the employees’ self-contained world where they live, work, shop and leave children at a creche, they are ‘not sure where [they] are in the year’ or ‘whether the day has ended yet or a new one has begun’. The sense of disorientation is compounded by a mysterious archivist who is analysing the recorded confessions of Tom, Steve from reception, an AV technician and others, and attempting to marshal them into a linear narrative. This sort of framing device usually brings order and context to a story, but Pester uses it to layer on confusion. We are left uncertain as to whether the archivist is working in the present looking back at the past, or in the future looking back at the present.

There is much poignancy in the plight of the workers, who struggle to retain a sense of self as Capmeadow erodes their individuality. A technician feels unnoticed – like ‘the crumpled napkins or the pile of coats’. A line manager has ‘no shadow’. Tom’s ‘missing’ daughter comes to represent something he has lost. With her sparkle and quirks she is a ‘blaze of light’ and personality, suggesting Tom’s breakdown is not just motivated by fear but a yearning for the person he once was. The relationship between Tom and Hen is beautifully observed, its heartfelt nature strikingly different to the soulless interactions of group conference calls. ‘Even the smell of an office was the first sensation of feeling myself fade away’, Tom says.

Inevitably, there are outbursts of rage, panic and violence, which the corporation attempts to contain by employing wellness platitudes and harvesting signs of anxiety for data. Tom joins an online meeting in a tropical garden entangled in vines, his hands smeared with slime, watched by a strange eye.

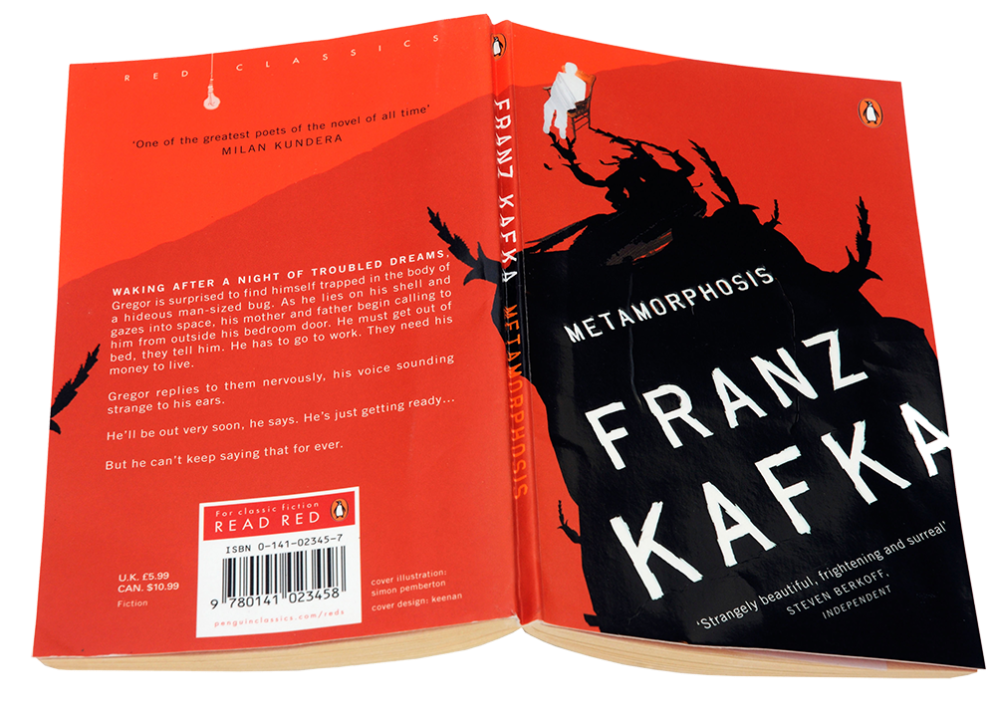

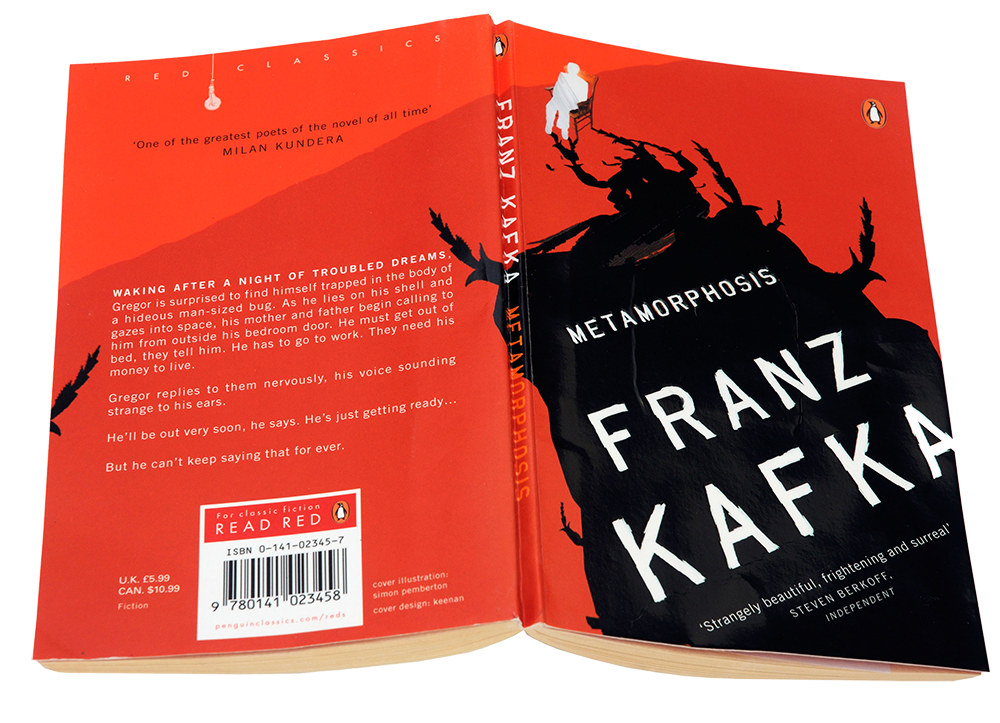

The tradition of the office worker rendered with absurdist humour can be traced from Flaubert’s Bouvard and Pécuchet, Melville’s Bartleby and Kafka’s Gregor Samsa through to the characters in the popular TV series Severance. But whereas Bartleby represents a delicious rebellion, Pester’s characters fail to fight back and descend instead into breakdown and broken acceptance. The result is a fever dream of a novel – disconcerting, strange and unexpectedly touching.

Comments