The Thing With Feathers is an adaptation of Max Porter’s acclaimed novella about a widower who is left to raise his two sons after his beloved wife’s sudden death and whose grief is embodied in the form of a monstrous, giant black crow. It stars Benedict Cumberbatch, who gives his absolute all, but while the film deploys psychological horror tropes it’s too mired in a pit of despond to be anything other than a misery fest. Also, while the crow works as metaphor in the book (it’s a rather wonderful book, as it happens), on film it’s a disaster. Unless, that is, you too see grief as a big talking bird that is very clearly a fella in a costume.

Crow, aside from clearly being a fella in a costume, is also, it turns out, from Lancashire

The film opens on the day of the funeral. Cumberbatch’s character, only ever known as ‘Dad’, tells his boys ‘you did really well today’ before carrying them to bed then weeping on his own. Over the coming months we see their London house become more and more shambolic and untidy as a way of screaming ‘absent mother’. He appears to be the sort of dad who has never looked after his own children before. (There would be very little to work with if the genders had been reversed and Mum had been widowed.) Dad is too ill-equipped to even pour out cereal. Bereavement is savage – we’ve all been there – but, even so, it’s not that hard. Cereal, that is. You just upturn the box over a bowl and there you have it.

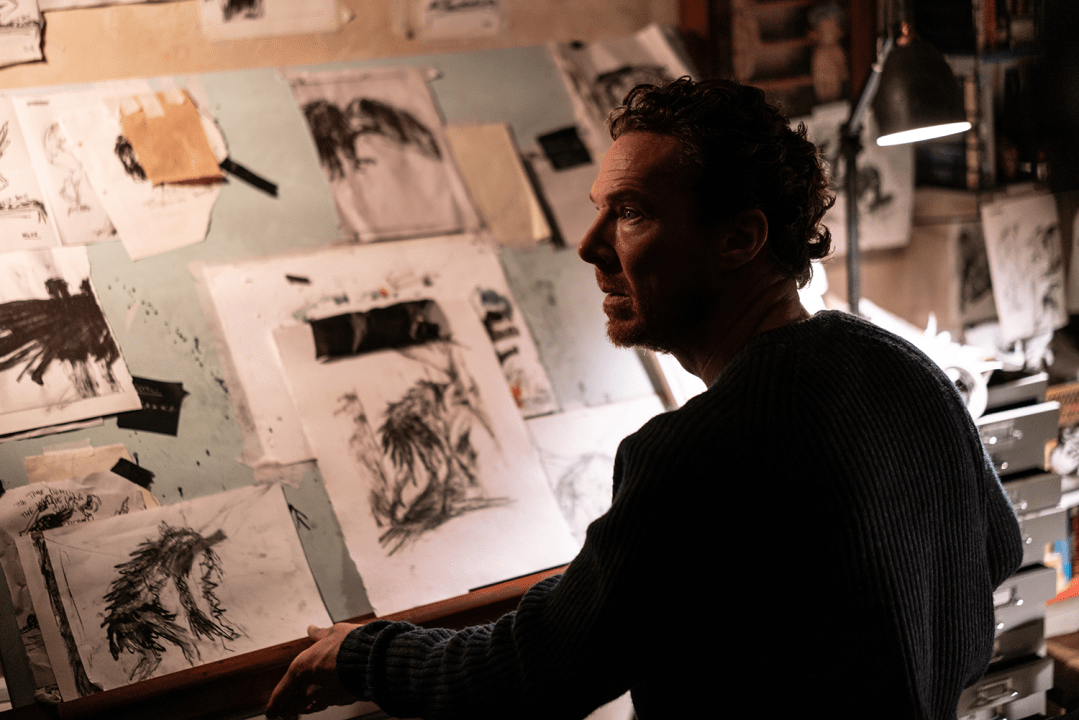

Crow is crow-sized initially. Crow sits outside on the windowsill, cawing harshly, then crashes into the window with a mighty, feathery thwack. It soon becomes man-sized and everywhere. Crow is patrolling the hallway, or in the living room, or following Dad to the supermarket. Dad is a graphic artist whose illustrations become blacker, inkier, more pain-filled and crow-ish. He sometimes caws like a crow. He sometimes curls his hands into talons. Grief has Dad in its grip, we can safely say. This metaphor isn’t shy. It is unrelenting. Crow beats Dad up. Crow is viciously spiteful. Crow tells him: ‘You are such a cliché. You’ll be taking out the photo albums next. You’ll be talking to a headstone.’ Crow’s voice is David Thewlis. Crow, aside from clearly being a fella in a costume, is also, it turns out, from Lancashire. If you see grief as a big talking bird that has flown in from, say, Blackpool, you may not need as much convincing.

Crow is played by actor Eric Lampaert and, fair play, no CGI is involved, but I was never frightened by it. Perhaps this is why the jump scares fail. Mostly, I was thinking: ‘Poor Eric, he must be hot under all that.’ It’s also a crow that doesn’t have much of a personality beyond hectoring. If you haven’t read the book it will be hard to fathom how or why it fulfils a therapeutic need. The film is actually at its best when Crow isn’t in a scene and it’s a quieter story of everyday bereavement. The two little boys exist mainly as ciphers for their father’s story but in the brief moments we see the effect of their mother’s death on them – one starts wetting the bed, the other starts playing up at school – there are fleeting moments of true emotion.

The film hangs on Cumberbatch giving good anguish and he does give top, five-star anguish but it’s not sufficient to sustain a film that otherwise has barely any plot. Stop wallowing and pour out the cereal for those poor boys! That’s not what this wanted me to feel but it was my main feeling throughout.

Comments