‘Who the hell is Disraeli?’ This, as a gleeful footnote in Douglas Hurd and Edward Young’s new book reminds us, was the response of John Prescott when asked on television what he made of Ed Miliband’s speech last year extolling the virtues of Dizzy’s world-view. Actually — as their book goes on to make clear — Prescott asked the right question. Who the hell was Disraeli? He certainly wasn’t anything close to what posterity — in search of a Tory Great Man — has made of him.

Not only, they tell us in this vigorously debunking romp through his political life, did he never use the phrases ‘One Nation’ or ‘Tory Democracy’, he was actively hostile to the concepts that they are now understood to represent. He ‘preferred to flirt with phrases about the aristocratic fundamentals of British society’, and no sooner had he passed the Second Reform Act than ‘he set about using the redistribution proposals to protect Tory rural constituencies from the new working-class voters in borough seats’. As for ‘One Nation, Disraeli actively repudiates it: he simply was not interested in a classless society.’

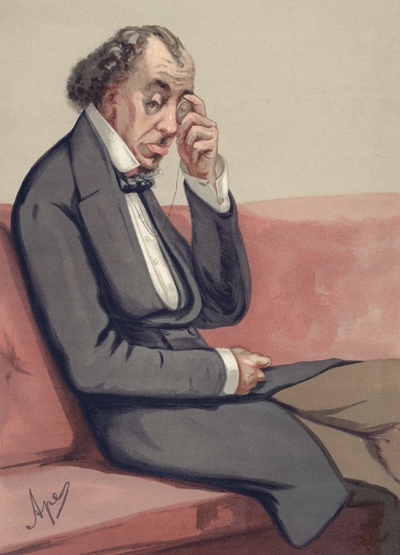

Then again, even that is probably to paint him as more consistent and ideologically high-minded than he was. In the Hurd-Young version, Benjamin Disraeli believed in more or less nothing except the further advancement of Benjamin Disraeli. He was — pick your quote — ‘an unscrupulous charlatan who believed in nothing’; an ‘unprincipled adventurer’ embracing an ‘unscrupulous nihilism’; ‘a bizarre, overdressed, bankrupt novelist who liked the sound of his own voice’.

The ‘Two Lives’ of their title refer to the real life of the man, and to the self-created myth that has eclipsed it. Six years after his death the ‘Primrose League’ honouring his memory attracted half a million members. He has more entries in the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations than any other prime minister. David Cameron and Ed Miliband vie to steal his clothes. Let them take care with that.

Disraeli’s true legacy, as Hurd and Young see it, was twofold. In the first place he brought a novelist’s style to politics, injecting imagination, flair and wit into an age of gravity, dullness and pomposity. He was funny. He gave us the phrases ‘a row of exhausted volcanoes’ and ‘the greasy pole’. He compared Bulwer-Lytton’s Irish wife to a hod of mortar and a potato. On his deathbed, told that Queen Victoria was anxious to visit him, he said: ‘No, it is better not. She would only ask me to take a message to Albert.’

In the second place, he was ‘one of the first career politicians’, for better and for worse. For better: he understood the importance of party discipline; it was on his watch that Conservative Central Office came into being to manage elections and water the grass roots, and on his watch that the parliamentary party started to be briefed on the contents of the bills that the government was to bring forward. Also, he was a parliamentary tactician of brilliance.

For worse: he was in it for himself. He wanted to be famous. He was a fantasist — extravagantly reinventing his own background. He was a liar — flatly denying in parliament that he had ever petitioned Peel for a job. He was an egregious flatterer and a shameless sponger. He was a potboiling novelist and an occasional plagiarist. As a young man, he was involved in a disreputable if not outright fraudulent scheme to pump shares in non-existent mines, and there’s even a charge of petty theft to answer (he made off with the chancellor’s robe worn by Pitt). His vanity and ambition, and his oratorical panache, invite comparisons with Boris Johnson (Hurd and Young make the comparison). But he also resembles nothing so much as a 19th-century Jeffrey Archer.

His main interest in entering parliament in the first place was not to serve his fellow man, but to enjoy an MP’s immunity from arrest so as to avoid debtor’s jail. He set out to destroy Peel (Hurd’s sympathies are clearly with that decent and conscientious man) not because he had any deeply held views on the Corn Laws but because doing so was an opportunity to make a name for himself in politics. He flip-flopped on Protection as soon as it suited him. In 1867 he added half a million souls to the franchise while his colleagues were out at dinner — not out of some principled constitutional vision but simply because doing so presented an opportunity to kick Gladstone in the pants.

Again and again we see him treating politics as a competition to win rather than an instrument to achieve ideological or social ends. When he eventually became prime minister he had enormous difficulty assembling a Queen’s Speech because he didn’t have any policies at all: ‘He relished the trappings and privileges of office for their own sake’ and ‘dismissed as humbug the idea that a prime minister should do anything, let alone concern himself with the details of policy or the drudgery of departmental work’. In fact, he nodded off in cabinet while policy was discussed. As chancellor he presented a budget ‘of great courage, immense complexity but no mathematics at all’.

He liked the idea of directing foreign policy — all that intrigue and grandeur — but he couldn’t be bothered to so much as read a map. He subscribed to the notion that Russian control of Constantinople would endanger Suez, but ‘in reality Port Said, at the head of the canal, is nearly a thousand miles by sea from Constantinople and much further overland’. He presented gaining control of Cyprus as ‘the key to Western Asia’, but it took Lord Granville to point out that ‘Cyprus was in fact further from the Dardanelles than Malta, which Britain already possessed’.

Did he believe in anything? He does appear — despite his Anglicanism — to have been passionately attached to his Jewish background, and he stuck his neck out to support Jewish emancipation. He also seems to have been capable of genuine gratitude — not least to his silly and adoring wife Mary Anne, who

never could remember which came first, the Greeks or the Romans, and would drop into conversation comments such as ‘You should see my Dizzy in his bath.’

This is an invigorating account, bracingly cynical and told with commanding ease — at least one of these authors has been around the political block a bit — and a lovely dry turn of phrase. It isn’t exhaustive, and it’s far more interested in Disraeli’s politics than his private life. The authors dismiss ex cathedra as ‘slight and unconvincing’ evidence that he cheated on his wife, where Dick Leonard’s book credits Dizzy not only with infidelity but with one and possibly two illegitimate children.

Leonard’s joint biography of Gladstone and Disraeli is also a solid and well-told primer: less scathing about Dizzy, and bringing out splendidly the hilarious priggishness of his arch-enemy (after being battered by college hearties, Gladstone tells his diary how thrilled he is to be vouchsafed the chance to practise Christian forgiveness). The book ends by quoting Thomas Carlyle’s epigram: ‘Dizzy is a charlatan and knows it. Gladstone is a charlatan and doesn’t know it.’

In a number of small details — was Mary Anne’s ‘humble petition’ to Peel on her husband’s behalf written with or without Dizzy’s knowledge? Was Dizzy’s attack on David O’Connell a quotation or delivered in propria persona? Did Dizzy bribe his way to a parliamentary seat? — Leonard’s book differs from that of Hurd and Young, and neither cites sources in enough detail to settle it. But that in itself seems to me a happy token that the conversation has a way to run yet.

John Prescott’s question stands: who the hell is Disraeli?

Comments