In 1990s Russia, war veterans were a bossy, even aggressive presence, upbraiding people in shops and pushing to the front in the trolleybus queue. Complaining about this at some point, I was struck and shamed by a Russian friend’s reaction: ‘Oh, but it’s sad… Imagine how hard their lives have been, to make them like that.’

Last Witnesses consists of about 100 accounts by men and women who were children when the Nazis invaded. Without preface or context of any kind, their voices rise off the page — hesitant, desperate, terrified, matter of fact, poetic, bewildered. Their ellipses are loud with choked tears and still-raw fear. All we are told is the speaker’s name, age in 1941, and occupation when he or she talked to Alexievich; many admit that this is the first time they have spoken of these horrors, or even thought of them, since the war: ‘Today my soul won’t be still all day and all night.’ It’s hard to imagine a reader who would not feel the same.

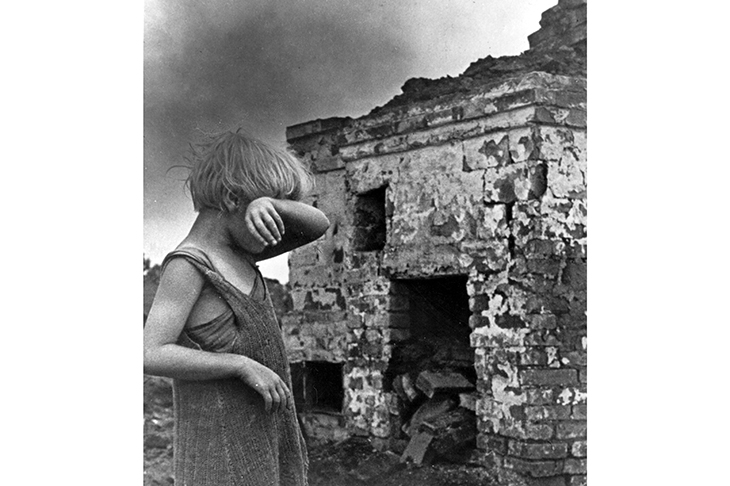

Alexievich carried out the interviews during the late 1970s in Soviet Belarus — perhaps the most thoroughly destroyed and terrorised region in all the huge arena of suffering that was the second world war. Hitler conceived of his invasion of the Soviet Union as a war of annihilation, and most German soldiers on the Eastern Front seem to have accepted the Nazi ideology that the civilians they encountered were ‘Jewish Bolshevik sub-humans’. Their orders, which they carried out punctiliously, were to slaughter or enslave them all. More than half of the villages were burnt. The large Jewish population was either imprisoned in ghettos or camps, or killed in more or less inventive ways. A particularly shocking scene describes Jewish children being drowned to the sound of ‘young belly laughter’ from a group of Nazi spectators. Children in orphanages — particularly those with fair hair — were drained of blood for wounded German soldiers. Nadia Gorbacheva (aged seven in 1941, now a television worker) comments that she still thinks a lot about ‘the inexplicable in the war’. She remembers a German plane circling above her as she crouched in a potato field. ‘I saw the pilot quite distinctly. His young face. A brief submachine gun volley — bang-bang!… The plane circles for a second time. He wasn’t seeking to kill me, he was having fun… How to explain it?’

If one pictures the whole country, including Stalin, taken unawares by Hitler’s invasion, how much more surreal and incomprehensible the experience must have been for the children. The childish gaze, innocent and unswerving, observes war with few preconceptions. ‘Everything gets stamped in a child’s memory like in a photo album. As separate snapshots…’ Details have a dreamlike clarity: a shiny bucket, a big beetle on the sand, the icy bodies of hanged partisans that ‘tinkled like frozen trees in the forest’, a blackened corpse with pale, unburnt hands. ‘Before my eyes a stone house ahead of us fell to pieces and a telephone flew out of a window. In the middle of the street stood a bed; on it lay a dead little girl under a blanket.’ ‘My mother lay on a sack, and the grain was pouring out of it. There were many, many little bullet holes…’

Last Witnesses was written as a companion piece to The Unwomanly Face of War, a collection of women’s memories of the war; some of the accounts in this volume are those of their children. Collected under Brezhnev, they weren’t published in Russia until 1985, and even then the censor removed sections that were considered ‘unpatriotic’ — the moment when children in an orphanage mistook German soldiers for their fathers; when a child hides under a bed after his mother is shot. ‘That would not have happened,’ Alexievich reports the censor shouting at her. ‘Where is the boy’s patriotic gesture?’

To non-Soviet eyes, however, one of the astonishing themes is not the children’s entirely natural fear and panic, but their extraordinary feats. At the age of nine or ten they are already scouts for the partisans, working in munitions factories or joining the navy. ‘Were we really children? We were men and women…’ The instant they find themselves somewhere safe, they put their heads down and sleep like babies.

Those who stayed with one parent held on to a shred of their childhood. They still starved; there were days when their mothers had nothing more to offer them than a bowl of hot water or strips of wallpaper. Their memories still spill over with nightmarish visions. Yet the orphans, in many cases, lost not only security and health, but their identities too; Lena (aged seven, now an accountant) forgot her own name in her terror. ‘Twenty-five years after the war I found just one of my aunts. She told me my real name, and for a long time I couldn’t get used to it…’

Alexievich was given the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2015 for ‘her polyphonic writings, a monument to courage and suffering in our times’. And what courage — children as young as four who took care of their siblings, shared their morsels of food with beloved pets, even with starving German prisoners of war. There is no shortage, either, of heroic kindness on the part of the adults. Jewish children are saved from the ghetto, despite it being a capital offence. An elderly Jewish couple hand themselves over to the Nazis so as not to endanger the family they have given shelter to. ‘I don’t understand what strangers are, because my brother and I grew up among strangers. Strangers saved us. But what kind of strangers are they? All people are one’s own…’

Yet these accounts speak not only of wartime itself but the decades-long tail of war. Tamara was a seven-year-old when war broke out: ‘I can never be completely happy… I’m afraid of happiness. It always seems it’s just about to end. The “just about” always lives in me. That childhood fear.’ Others report that they can’t stop eating, they stutter, they are incapable of crying, they suffer from constant nightmares. It’s difficult for them to form relationships; they are gruff, rude, strange. From a middle-aged woman with children of her own, simply: ‘I still want my mama.’ From a brutally tortured boy: ‘Decades have passed, and I’m still wondering: am I alive?’

‘With thousands of voices I can create — you could hardly call it reality, since reality remains unfathomable — an image of my time, of my country,’ Alexievich has written. ‘It all forms a sort of small encyclopaedia, the encyclopaedia of my generation, of the people I came to meet.’ In creating her ‘novel-choruses’ or ‘collective novels’, she is open about the fact that she uses a degree of poetic licence to edit her interviews. All history is, after all, selection, even when written by such an exceptionally modest and self-effacing author as Alexievich. Absolute reality, in the end, does remain unfathomable. And still the voices — so many of them — float out of her pages, across time, bearing layer upon layer of truth directly to our hearts.

Comments