Two years ago the Church of England decided to delay any public discussion of its deepest division, over homosexuality, until 2022. So this might be the year in which an already troubled institution has a dramatic public meltdown. Or it might be the year in which the Church of England sorts itself out a bit. Yes, really. Stranger miracles have happened.

There are grounds for hope, and not just on the gay issue. The Church has a core strength that it could draw on, and a core identity that could stand it in good stead, though one it is weirdly shy to assert.

First let’s admit that things haven’t been going so well, even while the gay issue has been kicked into the long grass. The pandemic has obviously been a nightmare for church attendance and finances, but it also deepened a dangerous ideological rift. It emboldened those who want to experiment with more flexible structures, which alarmed those who don’t, and who fear the demise of the parish. This rift is dangerous because it strongly overlaps with the old rift between evangelicals and Anglo-Catholics. At the same time the Church got drawn into the culture wars, with knee-taking progressive bishops irritating a large section of the faithful. The former bishop Michael Nazir-Ali was irritated all the way to Rome.

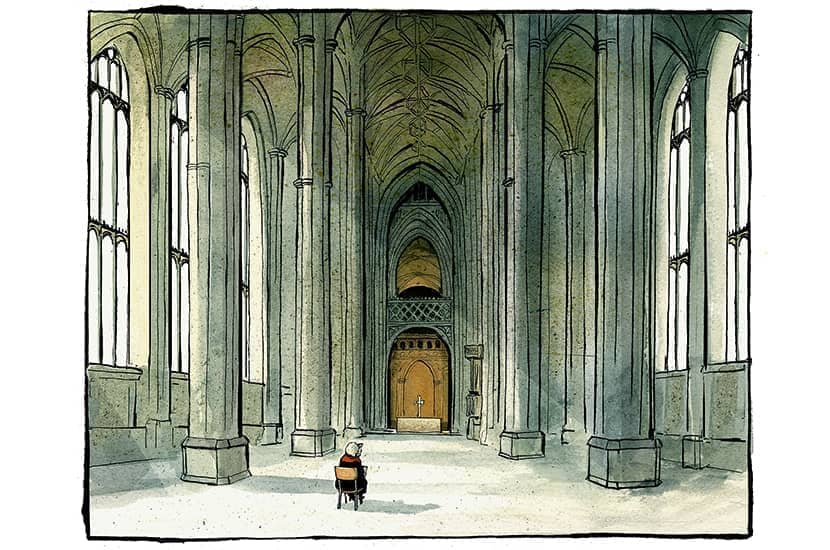

It might sound like crazy optimism, but challenging times can clarify minds, and prod an awkward, uncertain tradition into life. I refer not to the Church in general, which has pockets of passionate conviction, but to the core Anglican tradition of liberal Anglo-Catholicism. It is liberal in the sense that it affirms the liberal state and rejects a reactionary response to modern culture. It is Anglo-Catholic in the sense that it has confidence in ritual tradition, and is wary of simplistic emotional piety and bossy legalism. It prefers mystery, difficulty, open-mindedness. This is, in my humble opinion, the best Christian tradition, and in fact the best tradition in all of human culture. So why does it have all the self-confidence of a pimply teenager?

Some readers will be surprised some feel the Church lacks liberal confidence. Isn’t it full of trendy bishops trying to jump on woke bandwagons and modernise everything? Well, yes, there is a BBC-ish culture of political correctness, especially in the central leadership, but that’s not true liberalism, that’s just another form of tyranny. The Church could and should champion its own truly liberal identity. It only nervily apes secular trends because it has lost touch with its own tradition.

Consider the above-mentioned former bishop, Dr Michael Nazir-Ali. In an interview that he gave to this magazine he spoke of his early life in Pakistan, and named one of the key differences between Islam and Christianity. The former religion is ‘legalistic’, he said; it puts rules in the way of the believer’s relationship with God. His use of this contentious term struck me as a bit rich, quite frankly, in the context of his move from Anglicanism to Roman Catholicism.

Legalism is the belief that religion entails a ‘law’, or firm rules, about morality and ritual culture. Compared with other monotheisms, Christianity is relatively critical of this aspect of religion. You could even say that it separates religion and moral rules, arguing that God chooses not to be built into a particular moral system; he prefers to associate himself with an ideal of perfection. It is within Protestantism, and particularly liberal Protestantism, that this ‘post-legalism’ has been most fully attempted. This was a major ingredient of the modern liberal state: politics became secularised, as religious rules loosened. The Church of England partially and awkwardly signed up to this. It is joined at the hip to liberal culture. Yes, this makes it easy to criticise, but this is its special calling.

Liberal parishes must be free to conduct gay weddings, evangelical parishes must be allowed to refuse to

So the Church of England should regain some pride in its positive affinity with cultural freedom. Admittedly this will not in itself get agnostics back in the pews: secular liberals obviously don’t think they need any lessons on cultural freedom. But it is a crucial part of Anglican identity, and only a church that has confidence in its core identity can attract people.

When the Church’s liberal Anglo–Catholic core finally rouses itself into life, its task is threefold. First it must simply assert its centrality in the Church. This means speaking up for the Anglican version of liberalism, and defying the fashionable post-liberalism that has over-impressed a generation or two of Anglican intellectuals, from Rowan Williams to Giles Fraser. It’s time for a nuanced approach, in which aspects of liberalism are criticised, but in which the basic Anglican affirmation of the liberal state is renewed.

Asserting its centrality in the Church also means treating evangelicalism with a bit less respect. For decades it has unbalanced the Church by drawing relatively big (and affluent) crowds with a style that grates on most Anglican sensibilities. Its simplistic idea of mission has dominated all recent attempts at innovation, which have been heavily backed by the archbishops, leading to discontent in the parishes. A case in point is the newish Archbishop of York, Stephen Cottrell: though he comes from the Anglo-Catholic side of the Church, his promotion led him to an uncritical embrace of the evangelical model of mission, with its grim middle-management diagrams and cheery facile slogans. Evangelicalism remains ebullient as ever, but thankfully its reputation for trend-bucking success is now fading: a recent report showed that its latest church-planting efforts were largely fruitless. This makes it easier to put it back in its box.

The second task is to begin to end the dispute over homosexuality. It won’t be solved overnight, or over-year, but the solution is clear enough. Diversity must be allowed: liberal parishes must be free to conduct gay weddings, evangelical parishes must be allowed to refuse to. The Church allowed such diversity over the ordination of women; there is no reason that this compromise should not be repeated.

I have sometimes felt that the Church was wrong to tolerate dissent on the ordination of women and let the traditionalists have their separate structures, but it turns out that it was providential because it set a precedent that can now belatedly be followed on an even more divisive issue. Only by embarking on this admittedly messy course can the Church reaffirm its affinity with the moral culture around it.

The third task is to renew Anglican worshipping culture, both within the parish system and beyond it. Bold innovation is needed, but it must be in tune with the Church’s core traditions. We need a paradigm shift in which every parish has a dual function. As well as staging weekly worship it should contribute to wider cultural projects, such as local festivals, collaborating with other churches and other cultural bodies. Every parish should have an extrovert creative wing, an in-house arts centre. The aim is a new Anglican culture of creativity, rooted in parishes.

It is not an easy fate for a Church to be joined at the hip to liberalism. It is open to charges that it dilutes Christian orthodoxy and is full of moral muddle. The former charge must be refuted, but the latter charge cannot be. Our Church is full of moral muddle. But that is because you and I are. It reflects us. It is the muddle of honesty. The alternative is a Church that issues clear moral rules that most of its adherents do not quite believe in. You might say that a Church with a positive view of liberalism is simply too weak to stand. This sounds like a hard-headed analysis, but it’s not true. Plenty of us still feel called to keep the experiment going, of Christianity plus moral honesty. We trust that God will not allow this form of witness to run into the sand. He might even have grand plans for it.

Comments