This isn’t a headline I was expecting to read: ‘Free schools could be a bigger negative for the Tories than Ed Miliband is for Labour.’ Given that Miliband’s net satisfaction ratings are minus 39, that was quite a shock. Do the people who disapprove of free schools really outweigh the people who approve of them by a bigger margin than that?

Well, no, they don’t, obviously. The headline, which appeared on the blog of Mike Smithson, a left-wing gadfly, was a reference to a YouGov poll on 20 June. Respondents were asked whether they supported or opposed the creation of free schools: 23 per cent were in favour, 53 per cent opposed and 24 per cent undecided. That’s minus 20, not quite in Miliband territory. But not good, definitely not good.

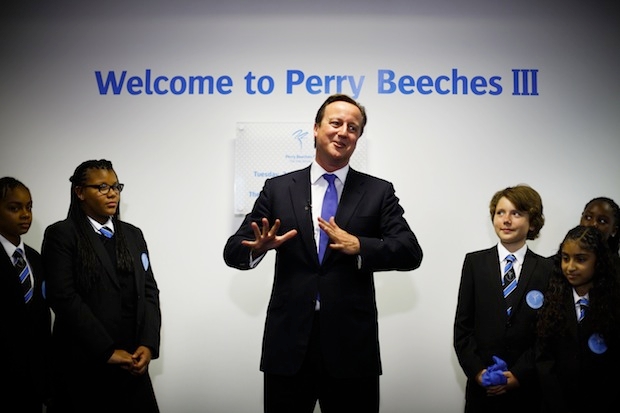

The first question I asked was: ‘Is it me?’ I’ve spent four years relentlessly promoting free schools — I’ve helped set up three — and I clearly haven’t been doing a good job. Admittedly, they’re popular with parents, with those free schools open since 2012 oversubscribed by an average of three applicants per place. The secondary school I co-founded is oversubscribed by ten to one. But the general public is sceptical. Even Conservative voters aren’t convinced, with 30 per cent in favour and 46 per cent against.

Has my obnoxious personality doomed the policy? When I was at Oxford I described myself as having ‘negative charisma’ — I only had to walk across a crowded room in which I knew nobody and nobody knew me and already I’d made ten enemies. As an aside, I think Ed Miliband suffers from the same problem. It’s not what he says, but the manner in which he says it. Something to do with his intonation and body language as he’s speaking. For a journalist, negative charisma is a surmountable handicap, but for a party leader it’s a catastrophe.

In all seriousness, though, I don’t think I’m single-handedly responsible for the unpopularity of free schools. Remember, the opponents outnumbered the proponents in 2010, so it’s not as if the public has changed its mind. And there’s a hard core of wreckers — the teaching unions, the left of the Labour party, the Socialist Workers’ party — that are much more energetic than the policy’s champions. And they’re particularly adept at persuading the BBC to run knocking copy. However often I appear on television and radio, it’s never going to be enough to counter the relentless barrage of negative propaganda.

Another thing to factor in is that this poll was conducted in the wake of the ‘Trojan Horse’ scandal in which various schools in Birmingham were infiltrated by Muslim extremists. In the question asked by YouGov, free schools were described as ‘new state schools set up by parents, teachers or voluntary groups which are outside the control of local authorities’. Even though none of the schools in Birmingham were free schools, the words ‘outside the control of local authorities’ may have conjured up an image of Muslim hate preachers hectoring innocent schoolchildren. In the minds of the poll’s respondents, being controlled by local authorities may not have sounded like a bad thing.

I’m confident that the public will eventually be won round to free schools, not just because more and more children will benefit from them over time, but also because of their results. The most important test of the policy will be when the first lot of free school pupils take their GCSEs — and I recently got into trouble with some parents at my school for telling the Year 9 pupils that the fate of the policy rested on their shoulders. ‘Don’t you think they’re under enough pressure as it is?’ complained one mother.

Well, yes, they are, but I’m still convinced they’re going to get fantastic results, as will the children in other free schools. The great virtue of schools like mine is that they’re beyond the reach of the Blob, which means they can teach proper subjects like Latin instead of media studies and rely on traditional teaching methods rather than ‘group work’ and ‘independent study’. In the same YouGov poll, people were asked whether it was right for children to go back to basics, learning about the kings and queens of England and memorising poetry: 43 per cent said yes, 34 per cent no. So the public approves of what we’re doing, just not the policy that has enabled us to do it.

The proof will be in the pudding. It’s just a pity that the first generation of free school students won’t be taking their GCSEs until a year after the election.

Comments