Rishi Sunak has been widely ridiculed for trying to spin the local election results as bad news for Keir Starmer. While acknowledging they were ‘bitterly disappointing’ for the Tories, the Prime Minister cited an analysis by Colin Rallings and Michael Thrasher, the renowned psephologists, showing that a similar showing by Labour in a general election would leave the party 32 seats short of an overall majority. ‘Keir Starmer propped up in Downing Street by the SNP, Liberal Democrats and the Greens would be a disaster for Britain,’ he said.

This was wishful thinking, according to John Curtice, the polling expert. He pointed out that the way people vote in local elections doesn’t mirror the way they’ll behave in a general. They’re more likely to vote for Lib Dems, Greens and independents in locals, he said, usually at the expense of Labour. The Tories, by contrast, didn’t lose many votes to Reform, because the party only contested one in six council seats. In those wards where Reform did stand, the Conservative vote fell by 19 points, an indication of what’s likely to happen in the general, where Reform has promised to fight every seat.

It’s worth remembering what a mountain Labour has to climb to win an overall majority

The bookies agree with Curtice and are currently offering 13/2 on ‘no overall majority’. Those odds are lengthening too – I got 13/5 when I put £50 on ‘no overall majority’ in December. But I still think that’s a decent bet because, like Sunak, I believe the chances of a hung parliament are underpriced. To be clear, I think the probability of Labour winning an overall majority is higher than 50 per cent – significantly higher. Just not as high as the pundits and the punters seem to think.

Take the by-election in Blackpool South, which was held on the same day as the locals. On the face of it, a big win for Labour, who overturned a majority of 3,690 to recapture the seat. But in fact the Labour candidate got fewer votes last week (10,825) than in 2019 (12,557). He won because the Conservative vote collapsed, going from 16,247 in 2019 to 3,218, not because of huge enthusiasm for Keir Starmer’s party. That’s of a piece with Labour’s national share of the vote in the locals, an anaemic 34 per cent, just nine points ahead of the Tories. Contrast that with Labour’s 43 per cent share in the last local elections before Tony Blair’s landslide in 1997.

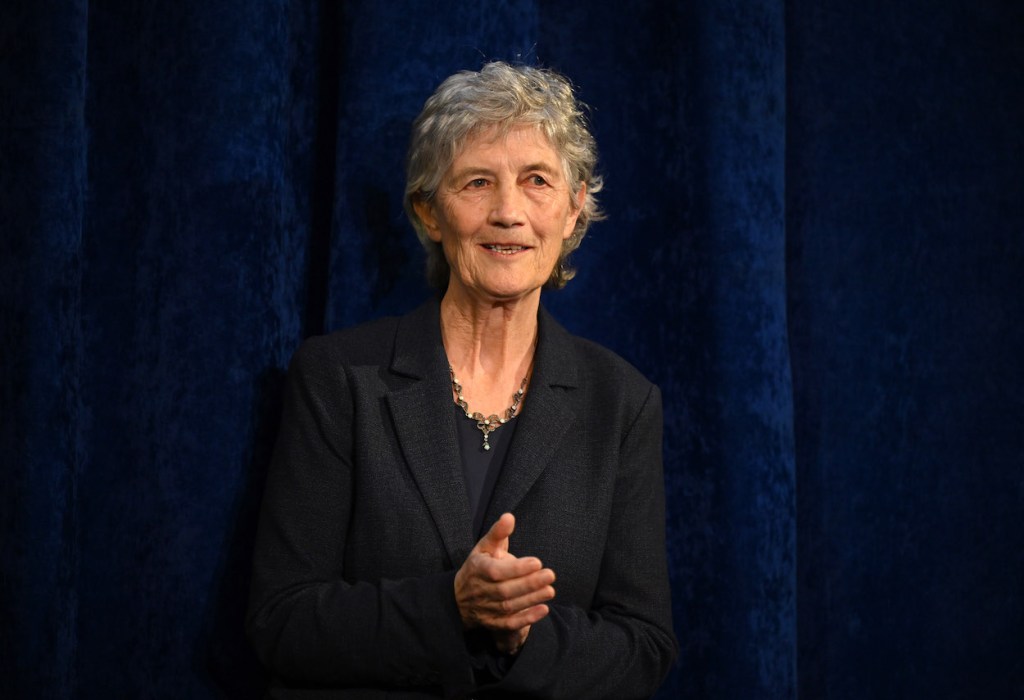

It’s worth remembering what a mountain Labour has to climb to win an overall majority. So poor was the party’s result in 2019 that to secure a majority it would need a bigger swing than in 1997 – and Starmer is no Blair. When I’ve made this point to Labour supporters, they retort that Sunak is no John Major, who did at least manage to win an election in 1992. But such is the natural conservatism of the British electorate that the bar has always been higher for Labour. The party has had 19 leaders in its 118-year history – 21 if you count Margaret Beckett and Harriet Harman – and only three have managed to win overall majorities. Is Starmer in that league?

I suspect Labour won’t poll a significantly higher share of the vote at the next election than it did last week. One of the reasons the party lost support to Greens and independents is because the candidates fighting under those banners were pro-Palestinian Muslims. An analysis by the Telegraph found that in those wards with the highest proportion of Muslim voters – Blackburn, Bradford, Pendle, Oldham and Manchester – Labour support dropped by an average of 25 points. Those voters will only return to the fold if Starmer changes tack on the Israel-Hamas war and gives in to some of the demands made by the new ‘Muslim Vote’ group. But that risks losing support elsewhere.

The question, then, is how many people who voted Conservative in 2019 will either transfer their allegiance to another party or sit on their hands? It’s this combination of disillusionment and complacency that Starmer is counting on. But during the election campaign, the Tories will do their best to paint Starmer as a spineless ditherer who will be bullied by the trade unions, held hostage by the hard left and terrorised by Britain’s enemies. They might just frighten enough voters to rob him of victory.

There’s one final reason for thinking Labour may be heading for disappointment, which is that the British electorate has a habit of not giving overall majorities to leaders it still has reservations about. That was the fate of Harold Wilson in 1974, David Cameron in 2010 and Theresa May in 2017. Is it so fanciful to imagine Starmer joining their ranks? The message of the locals is the electorate prefers Starmer to Sunak, but not by much.

Comments