France has been without an official government for seven weeks, the longest in the history of the Fifth Republic. A caretaker prime minister and government have been running the country for what President Macron declared the ‘Olympic truce’. That truce is now over, yet the President is in no hurry to appoint a new prime minister. One can understand why. A clear majority of French voted for alternatives to Macronist policies in the European and legislative elections, something the President refuses to accept. Whichever government is eventually appointed will unpick much of the President’s policies over the last seven years. And given that the locus of power will shift from the Elysée Palace to the National Assembly, it is no surprise that Macron prefers delay to what Le Monde calls ‘the spectre of his programmed effacement’.

Dismissive of time, Macron took three weeks to appoint Elisabeth Borne as prime minister, shattering the Fifth Republic’s record

One wonders whether Jupiter believes a government at all necessary for France. After all, Belgium survived for 592 days without one from 2019, and Holland for 7 months in 2023. Is it worth the bother? With a National Assembly split three ways and no group having the prospect of a functional majority, a stable government would be as elusive as under the Fourth Republic, when governments changed every six months, or even the Third, when the average was nine.

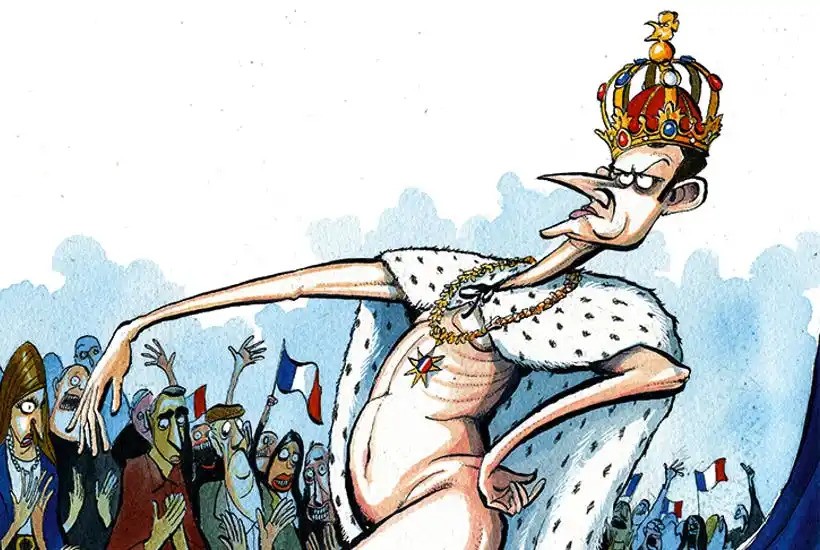

Readers’ comments on press articles are often more enlightening than the pieces themselves. So it was with a sardonic commentary on a recent Le Figaro article evoking the names of potential premiers. The incisive commentator questioned the need to appoint a French prime minister at all. For the last seven and a half years it is Emmanuel Macron who has occupied that role, he lamented, in violation of article 20 of the constitution, which states that the President presides and the government governs. The wag added waspishly, Macron also occupies the roles of all the ministers and junior ministers and that of the 577 députés and the 348 senators. The only role that Emmanuel Macron has not been able to fulfil, according to our caustic commentator, is that of… President of the Republic.

On assuming office seven and a half years ago, with the hubris that has come to define him, Emmanuel Macron went beyond merely declaring himself to be Jupiter, king of the gods: he regularly referred to himself as maître des horloges. The notion of punctuality being the politeness of kings could be no bridle for the Master of Time. His lateness is legendary. For the 80th anniversary of the D-Day landings he arrived late for the ceremony for veterans at the British Ver-sur-Mer memorial attended by King Charles, leading one veteran to lament apologetically to Le Monde: Macron ‘thinks himself a king, but he couldn’t give a damn about turning up on time.’

Dismissive of time, Macron took three weeks to appoint Elisabeth Borne as prime minister, shattering the Fifth Republic’s record. Little wonder that Jean-Luc Mélenchon and France Unbowed are threatening the President with article 68 to impeach him for constitutional dereliction of duty in not appointing a prime minister (theirs, of course). Mastering time, according to Le Monde’s Solenn de Royer, is the ultimate form of control.

Yet much as Emmanuel Macron might wish to prolong the present governmental parenthesis, grave decisions are afoot that cannot be executed by caretakers. The constitution requires a budget to be set for 2025 by this October; France under special measures from Brussels is compelled to demonstrate to the EU its capacity to reduce its 5.5 per cent budget deficit to 3 per cent and its debt to GDP ratio from 111 per cent to 60 per cent. The President has finally deigned to begin consulting parties on forming a government, with the Elysée suggesting an appointment could be made next week. With complete disregard for the outcome of two elections, it is no secret that the President will seek a premier least likely to contradict his own policies. But this will provoke a censure motion, more caretaker government and delay, simply because the constitution does not stipulate a time limit for appointing a prime minister.

In Ancient Rome during the last years of the Republic, at formal dinners three things were not done: arriving uninvited, sitting uninvited in the place of honour, being late. Few Romans failed to respect the elementary courtesy of not being late. Except Julius Caesar – to imply that he was above institutions. This intentional slight weighed heavily with a few senators on the Ides of March.

Comments