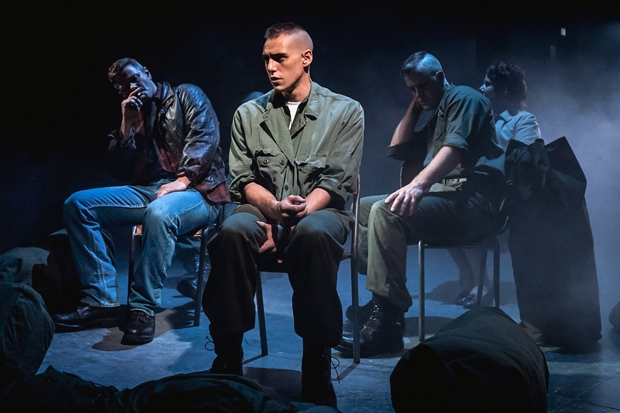

Wow. What an experience. A 1991 movie named Dogfight has spawned a romantic musical. We’re in San Francisco in 1963. Eddie is a swaggering, shaven-headed Marine and Rose is a shy, awkward waitress. Come to a party, he says. She refuses, prevaricates, reconsiders, accepts. They reach the venue; he ignores her. Furtive conversations in corners and a pervasive air of mystery suggest that something is up. The party, or ‘Dogfight’, turns out to be a secret Miss Piggy contest in which a bunch of insecure soldiers award a cash prize to the creep who invites the ugliest escort. When Rose learns she’s been tricked, she asks for an explanation. ‘You were disqualified,’ shrugs Eddie. This grisly set-up occupies the first act. In act two, the loathsome skinhead attempts to win back the woman whose Cubist features he thought would win him a few bucks from his spiteful peers. Rose, rather astonishingly, gives him a second chance.

As this barmy romance developed, I suffered a series of emotional calamities. My shock turned to bemusement, then to disbelief, then to anger, then to physical nausea, then to spiritual despair, and finally to indifference. In the closing moments I even experienced a golden beam of hope that this horror show, steeped in the sexual politics of the Stone Age, was a misbegotten satire. But no, it was in earnest.

The problem with Dogfight is structural. The romantic obstacles are badly placed. In a great love story, the couple must overcome external barriers, and their dramatic struggle brings out their courage, resourcefulness and humanity. In Dogfight the obstacles are internal. They rise from the characters’ personal failings. And the dramatic struggle reveals them as a pair of freakish saddos in need of therapy. He’s a cruel, snarky, woman-hating hypocrite. She’s a needy, cloying, dim-witted doormat. She may be a deaf doormat too. At their first meeting she tells him she writes folk songs and hopes to join the Peace Corps. He responds with this Socratic commandment: ‘If you want to change the world, become a Marine and shoot people.’ He’s not joking either. And she still dates him? Crazy.

The show is produced by Danielle Tarento with her customary zest and style. And she’s done an amazing job of casting the female lead. Rose has to be pretty enough to play the love interest but geeky enough to seem a credible recipient of the back-end-of-a-bus medal. And she has to sing and form a few chords on the acoustic guitar too. Laura Jane Matthewson covers every point in this challenging remit. A shame about the rest of the show. A couple of the ballads are sweetly melodious but the bigger numbers are over-strident. And the minor characters are as hard to like as the leads. One exception, a sleazy tart called Marcy, is played with oodles of erotic oomph by brunette bombshell Rebecca Trehearn.

Theatre 503 flings itself into the FGM debate with a series of four playlets. It’s an icky subject but these sophisticated, unpreachy scripts approach the issue with tact and delicacy. The first play is a verbatim piece featuring a random group of adults who chat about their everyday lives. A teacher, a postman, an ice-cream seller. It’s hilarious, some of it, and the comedy lowers our defences. A cynical road-sweeper tells us that public-spirited litterbugs like to toss garbage in his path and nod significantly at him ‘as if they’re doing me a favour’. An air hostess working for an international carrier (unnamed — to avoid lawsuits) claims that staff are given bribes to cover destinations with tricky and aggressive passengers. Nigerians, she says, are the rudest. But every nationality has its quirks. Snooty Brits, shouty Americans, two-faced Japanese. They’re all smiles on the plane but once they get home they start writing letters. Gradually these random pieces of testimony coalesce into a picture. A little girl’s name keeps cropping up. We realise that we’re watching fragmentary snapshots of her enforced odyssey from these shores to a rendezvous with an unsterilised blade overseas.

Later we see the grisly aftermath of a botched operation. The victim lies prone and wordless beneath a blanket and we’re left to deduce what fate has engulfed her. Victims of FGM fall into two classes, those who can recall the operation and those who were violated in infancy and who have no memories to haunt them. As adults, the victims use the verb ‘cut’ rather than ‘mutilate’ because it makes that tricky first conversation with a new lover slightly less awkward. ‘I’ve been cut’ sounds like a minor oddity. ‘I’ve been genitally mutilated’ seems to warrant a horrified crescendo on the trumpets. There’s a hopeful message here. Mothers who cut their older daughters are now declining to force the same horror on their younger girls. Or so they claim.

Comments