E.H. Carr’s 1961 book What is History? has cast a long shadow over the discipline. I recall being assigned to read it as a teen-ager, and it has prompted multiple reconsiderations over the years — as acknowledged by the editors in their introduction to this book. Reappraisals and conferences on ‘What is History?’ are launched with regularity. (One of the editors of this volume is Carr’s great-granddaughter.)

Aside from the reappraisal of Carr’s original work, the fact that books like this continue to be produced in academic history says something about the slipperiness of defining it in the first place — and the discipline’s own anxieties. Over the past century universities have been unsure whether history is part of the humanities or the social sciences.

Even within a university history department you’ll find competing views of what ‘historian’ means. There are some who believe their role to be dutiful recounters of archival fact, spending hours over spooling microfilm as the Bedes de nos jours; those who see themselves as storytellers and sustainers of a cultural patrimony; and those who feel a need to bring to light historical injustices, that we may take a more nuanced view of hazy nostalgia. (And that’s aside from the role that many academicians have: of educating the next generation.)

Outside academia, there’s the issue to contend with of ‘What is a historian?’— a challenge not really faced by other fields. Nobody says ‘I’m a physicist’ because they read the Richard Feynman lectures; you’d be surprised by the number of ‘historians’ whose qualification seems to be liking books about Napoleon — and who get quite shirty if you suggest someone with a PhD in the field might have more claim to the title. If history belongs to everyone, who is to control its meaning? As Helen Carr and Suzannah Lipscomb suggest, the conversation must be bigger than the academy.

As a shared cultural understanding of the past, history is our cultural identity. And it is an awareness of certain touchstones in the past that enable one to participate in culture, even at the most casual level. I wouldn’t be able to make a joke that my being up to my knees in mud is ‘like the Battle of the Somme’ unless I could assume that those within earshot know what the Somme was. Historical knowledge is also daily idiom; it cannot be teased apart from everyday culture.

The contributors here discuss the different forms of history that are practised and consumed, and the ways in which their sources and choices arise. I particularly enjoyed Sarah Churchwell’s piece about reading between the lines and seeing multiple meanings in sources. It is often what is not written, or only obliquely implied, that enables us to grasp the meaning of a historical record.

And indeed Helen Carr’s piece on the history of emotions, which suggests that not only did people in the past experience different things: they felt them differently from the way that we would. Much as psychologists today acknowledge ‘culture-bound’ syndromes, phenomena that only occur in particular groups, we could consider groups in the past as having time-bound responses to their situations.

Gus Casely-Hayford, the director of V&A East, offers an engaging and personal piece about his life in museums, and how he feels they can best convey the past to audiences. He writes on his goal of ‘opening doors to the past’, and his layering of analysis and autobiography to demonstrate a particular form of history. I hope he succeeds.

It’s often what is not written that enables us to grasp the meaning of a historical record

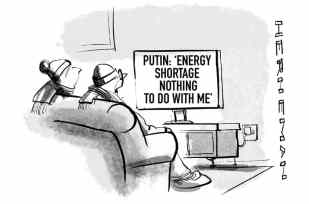

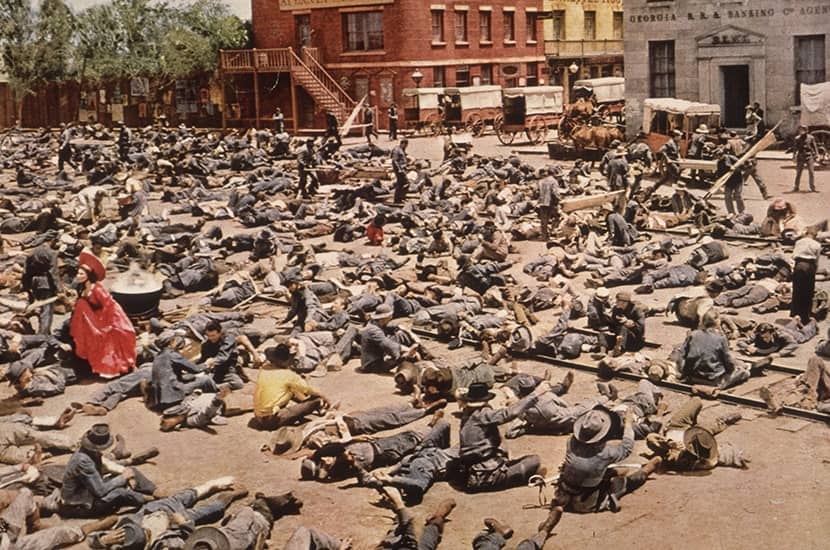

The screenwriter Alex von Tunzelmann attempts to tackle the issue of historical dramas, commonly criticised for their inaccurate depictions of the past. Like it or not, most people’s view of the past is to some degree influenced by a fictionalised version — whether they read Shakespeare’s Henry V, watch Gone With the Wind or play Assassin’s Creed. Tunzelmann takes the optimistic view that even inaccurate history might pique people’s interest and lead them to engage with more meaningful sources.

I was most impressed by Bettany Hughes’s ruminations on the classical world. She considers how knowledge, wisdom and culture are intertwined, and turns around the topic, suggesting that ‘the answer to the question What is history now? should more accurately, be another: What is wisdom, now?’ We are all the stories we tell about ourselves — and history is that: the stories that we tell.

Comments