What is striking about this evening’s revolt on the EU budget is that it was organised at lightning speed by the rebel camp. Mark Reckless and Mark Pritchard only tabled their amendment on Monday morning, whereas the rebellion of the 81 over the backbench motion for an EU referendum took weeks of careful planning. This time round, in just three days, the shadow whipping operation managed to stir up 53 MPs prepared to troop through the ‘yes’ lobby in favour of the call for a real-terms cut.

The whips themselves are already saying that they know the blame will land on Sir George Young’s head when they believe it wasn’t his fault. And even those who were the most enthusiastic signatories the Reckless/Pritchard amendment disagree that the whips should take the flak. Though some whips clearly went over the top – telling MPs that their rebellion could spark a vote of no confidence in the Prime Minister is not the way to calm things down on a non-binding vote – the real problem lies with the leadership.

Two rebels I spoke to this evening agreed: the Prime Minister isn’t listening to the whips’ advice. Their job is to come to him and tell him what the mood is among backbenchers, and to advise him on how to respond. One MP described it as a ‘needless cock-up’, while another told me:

‘It goes to the top. It’s unfair to blame whips or the No 10 political operation. The Prime Minister doesn’t listen to advice. Today is the consequence of that fatal flaw.’

The Prime Minister could have deflated the revolt considerably had he responded immediately to the Reckless amendment on Monday by making clear his personal desire for a real-terms cut, even if he added the caveat that this was highly unlikely. Instead, he only reassured backbenchers a few hours before the debate kicked off today, by which time the shadow whips were quietly confident that the motion would certainly be worth moving to a vote. Just before the vote, Number 10 conceded that it was highly likely there would be a defeat unless something dramatic happened.

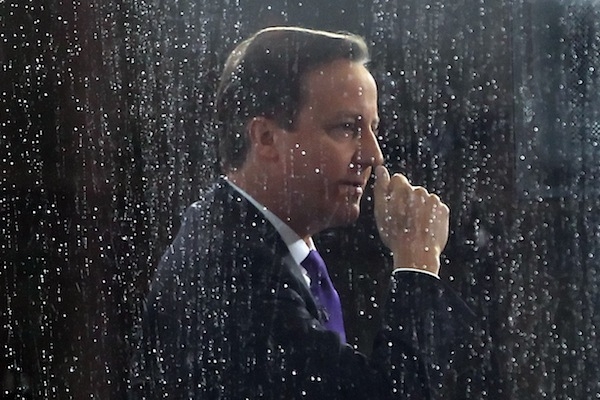

It is also significant how utterly ineffectual the offer of an audience with the Prime Minister or the Chancellor seemed to be as a key part of what little whipping strategy there was. I know of at least two Tory MPs who were not hardened rebels who, still wavering the day before the vote, were invited to meet David Cameron or George Osborne. Both turned the offer down. I understand that one of those MPs was almost affronted that this would be the first time the leadership had really spoken to them since the last revolt in the Commons. Number 10 does host ‘outreach’ drinks for backbenchers, but MPs don’t always leave those occasions in a more cheery frame of mind: apparently the Prime Minister doesn’t give the impression he particularly enjoys working the room or indeed that he enjoys listening to what his MPs have to say.

What will be worrying the whips more than anything is that this group of 53 MPs who seem to feel they owe their Prime Minister nothing is not small by any means. Having so many MPs who appear beyond rescue will panic the leadership far more than the actual amendment itself.

Comments