‘Wherever Sir Stafford Cripps has tried to increase wealth and happiness,’ wrote the Conservative Scottish journalist Colm Brogan, ‘grass never grows again.’ But Roundup has its uses. When Brogan made this comment, Sir Stafford was Britain’s postwar ‘austerity’ chancellor of the exchequer, a post he held from 1947 to 1950. Dry as dust, Cripps had rejoined the Labour party only two years previously, having served as ambassador in Moscow, then in Churchill’s war cabinet. A leading voice on the hard left, he had been expelled from Labour for his advocacy of co-operation with communists in 1939, but his judgment had proved shrewd. Hard-edged, essentially pragmatic, but fiercely moral and always driven by belief, he proved a very effective chancellor indeed.

I’m increasingly persuaded that Labour will be reaching for the weedkiller again, soon, and that the man to do the job will be John McDonnell, Labour’s shadow chancellor. I write this as a Tory who believes an effective, capable and high-minded Labour chancellor would represent a far greater danger than a loony ideologue. Mr McDonnell, I believe, is the former, and Tories are unwise to dismiss him as the latter.

But I’m not entirely sure he wants to be prime minister. He’s in some ways too serious for that. ‘I will be the first socialist Labour chancellor,’ he has said. This had been Cripps’s intention too. Instead, for much of the time he found himself (as most Labour chancellors do) firefighting.

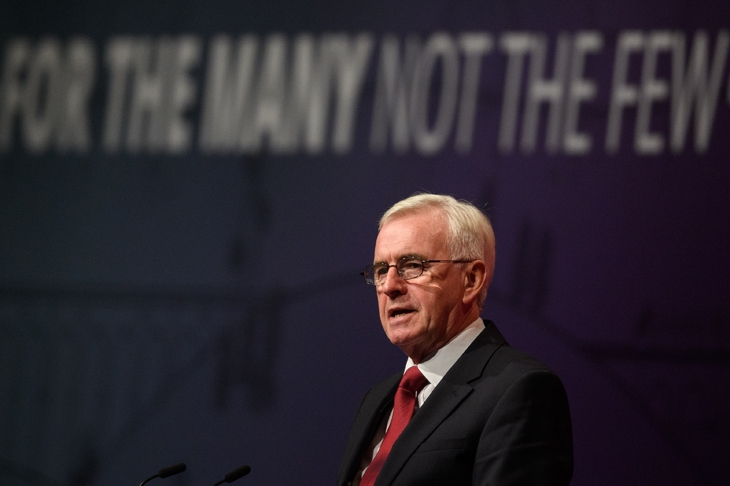

McDonnell is well-equipped both intellectually and emotionally for similar battles, some of which will be to douse flames that his own remarks have caused. Having secured his authority within his own party (he won four standing ovations during his speech at Labour’s Liverpool conference on Monday), he has started firefighting already.

The shadow chancellor’s tone has become more emollient. He went out of his way to praise British business enterprise in his Liverpool speech on Monday (singling out for his scorn only the rogue, tax-avoiding corporate giants) then headed off for a small-business Q&A where (by all accounts) he turned on the charm. The subtext beneath so much of what McDonnell says to wealth creators these days is: ‘Don’t worry, I don’t mean you.’

In recent months McDonnell has been talking to big business too. I’ve noticed a mellowing of his tone, even his body language, in the year since I watched him exude an air of bored insouciance at an event with the CBI’s director-general, Carolyn Fairbairn, at Labour’s 2017 conference. Business’s and the City’s response has been (to put it mildly) wary — and wary it ought to be — but the change in McDonnell’s manner has been noticeable. He is starting to think about government.

I sense a quest to warm up. Cynical journalists might call it the empathy business. To listen to the shadow chancellor in an extended interview on the Today programme this week was to listen to a changed man. He was almost Falstaffian. He seemed unable to stop chuckling, sharing little jokes with an indulgent (if sceptical) Nick Robinson.

Cripps’s patrician and Tory background contrasts with McDonnell’s thoroughly working-class credentials. His father was a bus driver (we are running out of ambitious politicians these days whose fathers were not bus drivers) but in other ways there are striking parallels. The first is an internal ideological fire. I’ve been reporting party conferences for the Times for 30 years this autumn and have lost count of the number of aspirants for high office whom you could not watch without smiling inwardly, ‘I wonder how much of this stuff he actually believes?’ Nobody ever levelled that at Cripps, and one would never say it of McDonnell.

Second is the intellectual self-confidence. Cripps apparently exhibited a dry, low-key but intense self-belief. He once casually remarked that defeat by the Germans might be good for Britain. McDonnell shares the lack of circumspection often characteristic of high intelligence. So assured is he that he almost never declaims, preferring the matey patter of a BA pilot informing us of the weather. ‘Might be a bit blowy, but it should calm down soon. Have a lovely holiday.’

But so relaxed is he about his rational grip that he’s been wont to make wholesale and unguarded remarks (a joke about assassinating Margaret Thatcher; support for Bobby Sands) that would come back to bite him were he ever to aim for No. 10.

As my generation in politics has discovered to our surprise, the new Britain can hardly remember the IRA, and Jeremy Corbyn’s ambivalence towards, if not sympathy for, that organisation has harmed him little. But some of McDonnell’s past utterances have been hard to finesse away. CCHQ will undoubtedly have a comprehensive list.

Finally, there’s religion. Cripps was a fervent Christian: so fervent that no church or sect could capture the totality of his faith. For much of his life he worked for the World Alliance for Promoting International Friendship through the churches; he became a teetotaller, it was said, in protest at drinking habits in the Commons; and a vegetarian. McDonnell began his career (or almost) by training to be a Catholic priest. He never did become, in truth, a classical Marxist; but though he may have abandoned the priestly vocation, a certain Jesuitical dogmatism has certainly not abandoned him.

Here’s my guess. The shadow chancellor may believe he can do more as our first ‘socialist’ chancellor than in the office of prime minister. Downing Street is show business. He’s keen on telling us the next Labour leader should be a woman, and talking up colleagues with less experience than himself — as though symbolism should come first for this job. I do wonder whether he is looking for a cat’s paw. It would not be out of character. In the end, for us Tories, Corbyn is unlikely to be the problem.

Comments