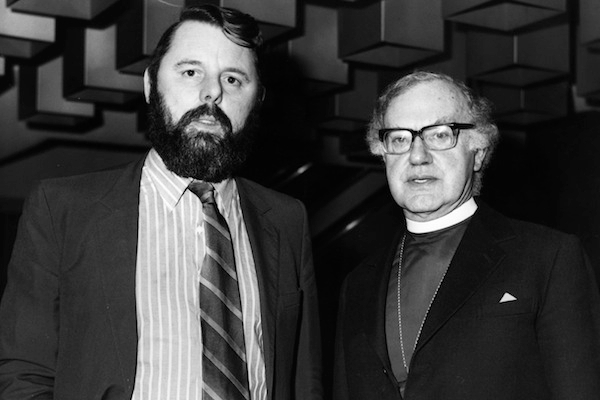

Earlier this month, while he was in Lebanon to highlight the plight of Christians in the Middle East, in particular those fleeing the fighting in neighboring Syria, Terry Waite, the former special envoy to the Archbishop of Canterbury, kissed and made up with Hezbollah, the militant Shia group that held him captive in Lebanon between 1987 and 1991. One probably shouldn’t blame Waite, now 73, for wanting to exorcise any residual demons of his 1,763-day nightmare, but in doing so he unwittingly gave Hezbollah dangerous and unwarranted legitimacy.

Talking to the UK’s Channel 4 news on his return, Waite declared, rather naively that he simply wanted to help ‘provide some degree of stability’ to Lebanon, a country he said was in ‘desperate difficulties, surrounded on all sides by dissention and trouble’.

Hezbollah, he added, ‘has moved in recent years from being an organization that seemed to be primarily concerned with terrorism… to becoming a fully fledged party’. He pointed out, correctly, that it has ministers in government and added, misleadingly, that it had formed an alliance with the majority of the Christian population and ‘that sort of relationship has to be encouraged in Lebanon’.

Oh Terry. They saw you coming my friend. Yes, Hezbollah has become more sophisticated since the mid-80s when it’s MO was lifting hapless westerners — journalists, academics and the like. Yes it is the most powerful party in the current Lebanese coalition, but did he know that it got there by toppling a democratically elected cabinet through the veiled threat of violence?

Yes, Hezbollah did form an alliance with the Free Patriotic Movement, arguably Lebanon’s biggest Christian party in terms of parliamentary seats, but this has less to do with the pursuit of sectarian harmony and more to do with the ruthless manoeuvrings of Lebanese politics.

The FPM is led by the former Lebanese army general Michel Aoun, who once fought a war with Syria before going into a 14-year Parisian exile. Aoun, whose party is part of the pro-Syrian March 8 bloc, wants the presidency and believes Hezbollah can eventually give it do him. In return, Hezbollah gets valuable Christian cover that it believes will soften its militant Islamic profile.

Waite was certainly sold on the idea, but there is a bigger, more sinister picture that he clearly didn’t see. The party he praised for having ‘moved on’ is slowly suffocating Lebanon’s fragile sense of statehood by its insistence of doing what it wants when it wants. It also poses a genuine threat to regional stability through its strategic military alliance with Iran, while its support of Syrian President Bashar Al Assad’s murderous regime, a key regional ally, has inflamed Sunni sentiment in Lebanon.

And just to show remind us that it hasn’t totally turned its back on its roots, at least four of Hezbollah members have been indicted by an international tribunal for their involvement in the February 2005 car bomb attack that killed former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri and 21 others.

Hezbollah’s genius lies in the fact that it operates on two levels. The rank and file believes the party has brought a sense of dignity and honour to Lebanon’s Shia, a sect that was for so long an underclass. It has a strong welfare arm helping its constituents with schooling, healthcare and other social services in a country where the state does little for those in need, while its military wing makes up a national resistance movement that forced Israel to leave its self-imposed security zone in south Lebanon in 2000 after 22 years of occupation and gave the Jewish state another spanking in its brief but bloody war in the summer of 2006.

But this narrative is only part of the story. The party’s other core business is being an adjunct Iran’s Revolutionary Guard and a key asset in Tehran’s current stand-off with Israel and the West. Instead of declaring job done in 2000 and laying down its weapons as many Lebanese, myself included, had hoped, it has spent the last 12 years adding to its impressive arsenal and is today arguably the most effective Arab “army” in the region, one whose very presence could ignite regional Armageddon.

Not only is Israel nervous, Hezbollah’s increasingly aggressive martial posturing has created an imbalance in Lebanon, a country that built on consensus politics.

The watershed moment came on 7 May 2008 when, in response to a government decision to shut down its private mobile network and sack a party-appointed security chief at Beirut airport, the party staged what was, on reflection, an attempted coup. After three days of fighting in Beirut and the mountains above the capital (during which not everything went Hezbollah’s way) the politicians returned to the negotiating table. Hezbollah got what it wanted, but the mask of martial purity and steely patriotism had slipped. It had used its weapons to achieve domestic political goals, something it swore it would never do.

Further problems, this time ideological, arose in 2011 when the Arab Spring eventually pollinated Syria. Those Lebanese who were still drinking the Hezbollah Kool Aid wondered why a party that had claimed to stand up for the oppressed was backing a regime that gunned down its own people for simply demanding reform.

Did Waite know that his trip was in all likelihood sponsored by a foundation that believes that only the Assad regime can guarantee the perpetuity of the region’s minorities? Did he understand that his hosts in the FPM and Hezbollah’s Aammar Moussawi, with whom he warmly shook hands, are determined to see the perpetuity of a system that is now being accused of dusting down its chemical weapons arsenal?

In fact does Waite know that, Hezbollah is far more dangerous today than when it took him hostage in Beirut on January 20, 1987? It is at this point that the complexities of Middle East politics begin to run rings around an elderly man trying to do the decent thing.

Comments