In 1887, Friedrich Nietzsche made a complaint about the modern world, writing in The Gay Science:

Even now one is ashamed of resting, and prolonged reflection almost gives one a bad conscience. One thinks with a watch in one’s hand, even as one eats one’s midday meal while reading the latest news on the stock market; one lives as if one always ‘might miss out on something’.

Johann Hari’s Stolen Focus rehearses this complaint. We fill our lives with distractions, he says, and have no time to think. He adds a few new problems, though they’re also pretty familiar: we are constantly on our phones; social media is bad for us; we don’t read enough books; we don’t spend enough time doing nothing; we work too hard; we are too fat; our diet is bad; we don’t sleep well; the internet is addictive; businessmen make money out of keeping us glued to our screens; children are not allowed to play.

Hari takes these complaints to various ‘experts’ for insights, who patiently explain things to him, and he gradually becomes more enlightened. But it’s all banality and platitude. An aperçu from Joel Nigg, ‘one of the leading experts in the world on children’s attention problems’ is: ‘We have bad food… and people are getting fat.’ Another reckons that to get stuff done we need to concentrate: ‘If we want to do what matters in any domain we have to be able to give attention to the right things. If we can’t do that, it’s really hard to do anything.’ More breakthrough thoughts include: ‘There’s something about speed that feels great’; and ‘what happens with our cellphones is that we put a thing in our pocket that’s with us all the time that always offers the easy thing to do rather than the important thing’. Then there’s the revelation from the Greenpeace guy: ‘He explained that Britain was the birthplace of the industrial revolution, and this revolution had been powered by one thing: coal.’ Johann, did you seriously not know that?

There are some good bits. I liked the chapter about B.F. Skinner, the evil inventor of behaviourism, whose life project — how to get people to do what you want them to do — underpins Silicon Valley’s behaviour modification techniques. But even here, the work of the tech writer Jaron Lanier on how social media works is vastly superior. Hari should have spoken to him.

He concludes that things are not our fault but capitalism’s. It’s the merchant class, the greedy people, who distract us for profit; and politicians distract us for power. Many will agree with the practical solutions Hari sets out. Yes, a universal basic income could be a good idea. And a four-day week. And why not go for a walk? But haven’t we read all this before? I kept hoping for some original insight or revelation, but was disappointed. And Hari’s solution to phone addiction? Buy a safe with a timer and lock the phone in it.

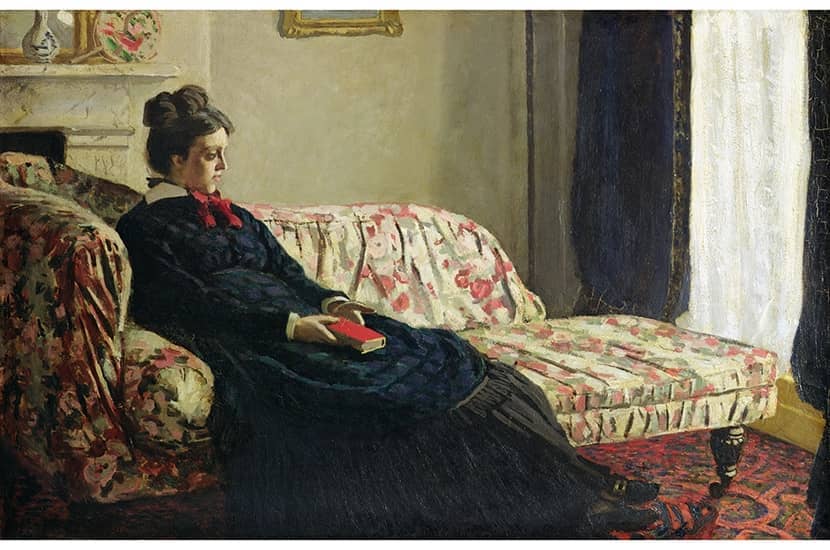

Moshe Bar’s Mindwandering also has a simple message. It’s a nice one, but equally familiar — that daydreaming can lead to creativity and ideas, and meditation is beneficial. He is a neuroscientist, so this comes with a pleasing aura of authority. But anyone who’s read Wordsworth or Blake or Virginia Woolf or the Bible or Lao Tzu or Hamlet’s great soliloquy will find nothing much new here. Dr Johnson famously lay in bed half the day thinking, and then sat down to write his essays at the deadline. Even the industrious Dickens went for long walks every afternoon to clear his head and think and dream.

Bar is also given to expressions which aspire to a Gladwellian snappy simplicity but don’t quite make it: ‘I believe that you should think less to think better. But if you do think, think broader to feel better.’ Yer what, mate?

And, I’d argue, there’s a basic error. Bar reckons that happy people are creative. If you’re miserable, he says, your mind is so busy with the misery that you’ll have no space left to come up with good ideas. But much of the greatest literature, music and art has emerged from unhappy states, from Keats’s ‘Ode on Melancholy’ to the diaries of Dr Johnson and countless others.

If you really want to pay attention and improve your mood I’d give these two books a wide berth and read Nietzsche instead.

Comments