‘Paris, like many old cities, is saturated with blood.’ The food writer Chris Newens certainly knows how to draw the reader in. A Londoner who has lived in Paris for the past ten years, he sets out to eat his way through all the arrondissements, starting with the 20th and spiralling backwards through the coil of the capital. Each chapter evokes the history and atmosphere of a different neighbourhood and focuses on one dish, which the author then attempts to cook in his authentically cramped Parisian kitchen.

Newens, who read anthropology at the LSE, comes from a family that ran a bakery and tearoom for six generations and had their own recipe for the custard tart known as Maid of Honour. This expertise equips him with the right sort of outsider-insider perspective on the experience of eating in Paris – or rather, as he puts it, for this is a book that looks beyond the ‘thousand clichés’ of the Parisian bistro, in ‘all the Parises’.

Blood and meat loom especially large in his exploration, reflecting the fact that Paris is in no danger of becoming vegetarian any time soon. On an early morning visit to the wholesale food market of Rungis, Newens’s guide hands him a box of ‘an uncanny organic weight’, which turns out to be full of brains. ‘It was time for a drink,’ Newens comments. In the 19th arrondissement, he searches for the perfect kebab shop, known in French as a kebaberie, and his quest takes him from the former La Villette slaughter yards to the somewhat sinister suburban factory that supplies most (though not all) Parisian kebaberies. Then, having secured instructions from a serious Turkish cook, he purchases a quantity of meat that ‘initially looks like a prolapse’. Once conveyed to a friend’s house outside Paris, however, where a garden makes it possible to light a fire, the homemade doner kebab is slowly roasted to miraculous savoury deliciousness.

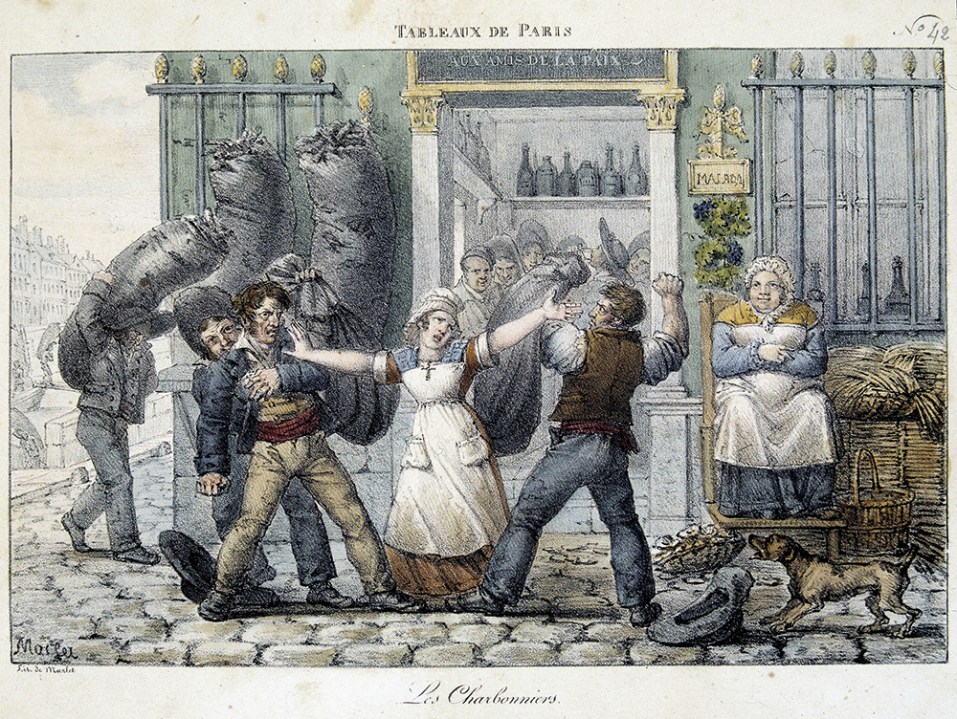

The appeal of this funny, well-informed book, which covers much historical, cultural and sociological ground, lies in its sense of adventure and lack of cosy sentimentality. Food for Newens is thrilling and joyous and engages him bodily – he mentions in passing that he is diabetic. It is not a nostalgic book, but it is one in which a sense of history matters. There are fascinating evocations of 19th-century French provincial migrants: for example, the Aveyronnais, known as bougnats, who came to Paris to sell their coal, offered a drink of their regional wine on the side and then stayed on to open many cafés, including such classic Left Bank institutions as the Café de Flore and Les Deux Magots. They also brought with them aligot, the rib-sticking, velvet-smooth dish of potato mashed with Tomme cheese that in the Aveyron used to be served to pilgrims on their way to Santiago de Compostela, and which in Paris bistros has now sadly been displaced by frites.

Blood and meat loom large, reflecting the fact that Paris is in no danger of becoming vegetarian any time soon

Newens also traces the story of the Breton migrants who brought buckwheat pancakes to Paris and whose legacy remains in the crêperies of Montparnasse. After traipsing across muddy fields from a bus stop in deepest Brittany, the author turns up, an unexpected visitor, at a buckwheat mill to secure a bag of flour. Elsewhere, there are conversations about the myriad family recipes for couscous, which yield insights into North African Sephardi experiences and those of the pieds-noirs who moved to France at the time of Algerian independence. Newens also debunks the French myth that Vietnamese pho, the complex soup dish, got its name from the French pot-au-feu.

He takes some risks, including venturing into the Bois de Vincennes’s encampments of homeless people to ask them about what they like to eat and visiting a restaurant solidaire (soup kitchen). These passages might easily have jarred in a book that also describes high-end gastronomy. But Newens is a self-aware narrator who recognises in himself expressions of bourgeois complacency or nervousness. Another tightrope exercise is the Houellebecqian chapter in which he visits a swingers’ club with a hammam (apparently one of the world’s capitals of swinging is Paris, where it is called libertinage) and, clad in a towel, examines the food on offer – a depressing meat-platter brunch, complete with halal turkey.

More uplifting is his account of eating in a vast bouillon – the name comes from the mid-19th-century restaurants where butchers would serve cheap, hot meat broths. Nowadays a bouillon provides a full menu of traditional French dishes – from oeuf mayonnaise to blanquette de veau – for large numbers, often not taking advance bookings. When Newens speaks to an hôtesse d’accueil, who greets diners and allocates tables, she describes her job as ‘almost like playing Candy Crush’. And there, once given a seat, Newens ‘luxuriates in the small privacy of eating’ while the room bustles around him like a medieval feasting hall. Moveable Feasts is an inspiring feat of curiosity and appetite.

Comments