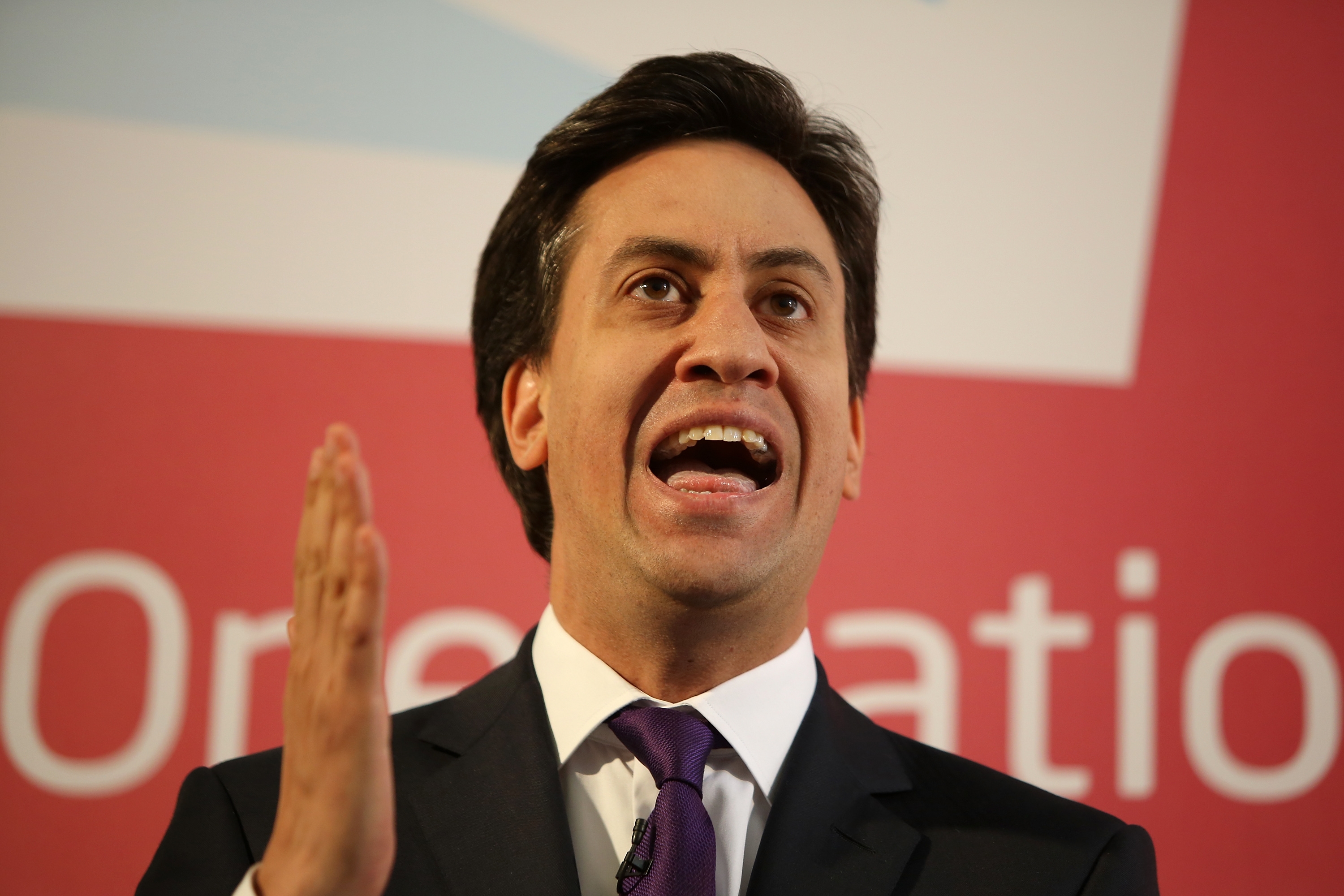

Tony Blair has welcomed Ed Miliband’s “big speech” on reforming Labour’s relationship with its Trade Union backers. And so has Len McCluskey, chief potentate at Unite, the Union whose allegedly nefarious activities in Falkirk have prodded Miliband towards reform. Blair expects Miliband’s proposals to change everything; McCluskey, presumably, is confident any changes will prove largely cosmetic. They can’t both be right.

But, actually, it is a little unfair to put “big speech” in inverted commas. This was, or at least has the potential to be, a transforming moment for the Labour party. Granted, no-one is quite sure how this will happen – and the detail matters – but everyone agrees something is afoot. (Tim Stanley, for instance, suspects Miliband will betray the Unions; Dan Hodges reckons today’s events show Miliband is prepared to become Prime Minister. You pays your money and takes your chances.)

Miliband may have been forced into a corner by the Falkirk crisis but, if he follows through with these plans, he will have shown some courage. The Tories have had two stout cudgels with which to set about the Labour leader. First that Ed is a creature of the Unions, in their pocket, and beholden to them. Secondly, and relatedly, that he’s too weak, too lacking in the right kind of moral fibre, to be trusted with the keys to Downing Street. Neither of those arguments – previously quite persuasive – look as strong today as they did last week.

So, in that sense, Miliband has improved his position even if the actual implementation of his mooted – planned is too strong a word – proposals won’t happen before the next election. He has spiked a brace of hard-pounding Tory guns. Or so he hopes.

But the speech was more just another tactical ploy. It opened a path to a different kind of Labour party. If all Union members are required to opt-in to the political levy and if doing so then makes them full and proper members of the Labour party then Labour might just be on the way to becoming something we’ve not seen in British politics for some time: a political party with a mass membership.

That, at any rate, is the theory. Moreover, it would be a party in which the leadership could speak to – and consult – the membership without having to go through the Unions. As Isabel says, Miliband wants everyone to know that this will probably cost the Labour party money and perhaps it might, at least in the short term. In the longer-term, however, it opens a path to a different kind of fundraising in which individual members are encouraged to support the party with their money as well as their time. Again, it is about building a movement financed, at least in part, by a broad base of low-level contributors.

Which brings me to the London part of Miliband’s plans. He suggests that Labour will hold a primary to select its candidate for the next mayoral elections. All Londoners who register as a Labour party supporter would be entitled to vote. I don’t suppose anyone knows how many Londoners would be interested in taking part in this process but it’s reasonable to assume plenty would.

By way of comparison, however, some 330,000 New Yorkers voted in the 2009 Democratic mayoral primary. So let’s suppose (optimistically!) that at least 200,000 Londoners out themselves as committed Labour party supporters. That’s another 200,000 email addresses to be fed into Labour’s databases and another 200,000 voters who can be asked for cash. Couple this with a cap on individual donations to political parties and you begin to see how, at least in theory, the Labour party could steal a march on a dying Conservative party struggling to retain existing members, far less recruit new ones.

In other words, Miliband might have started something today. If – and it is a mighty if – his proposals are implemented, Labour will look a little less like your father’s beer-and-sandwiches Labour party and a little more like, well, the Democratic party in the United States.

A mass membership party – or even a register of reliable Labour supporters – could have other consequences too. It might change the way British politics is conducted. Political parties would have to spend more time talking to their members and supporters and less time chasing the elusive floating voter. Members and supporters, of course, would then be encouraged to spend more time on party issues, whether that be for a general election or, more frequently, a single issue campaign. The Labour party would be a little more like Amnesty International or Greenpeace and a little less like the parties we have now.

Of course and as any student of American political history knows, primaries neither guarantee better candidates, nor a more open or clean kind of politics. Indeed, they’re often liable to be captured by all those “special interests” everyone agrees are a Bad Thing. (Unite’s alleged deviousness in Falkirk is actually just a miniature version of what might be expected in a notionally more “open” primary campaign).

If primaries were adopted across the country, the primary would become more important in many seats than the general election. That’s unavoidable and it’s not necessarily unwelcome either since, at present, the party HQ often exerts considerable influence upon candidate selection. Frequently those candidates are from the “acceptable middle” of the party; the widespread use of more open primaries (even if restricted to Labour party supporters) might well produce a broader range of MPs.

But it would also weaken the party machine at Westminster since MPs selected via a primary are likely, I think, to feel they have a broader and certainly more personal mandate than MPs selected by a handful of local constituency apparatchiks. This in turn seems likely to make these MPs less likely to truckle to the leadership for the sake of party loyalty.

All of which is to say that Miliband appears to have started a process that, in time, may make British politics look and feel more like American politics than is currently the case. The effects of such a process will, doubtless, take some time to be felt but it is, wittingly or not, a bold or brave step towards a different kind of politics. Not necessarily better or cleaner or more open but certainly different.

Comments