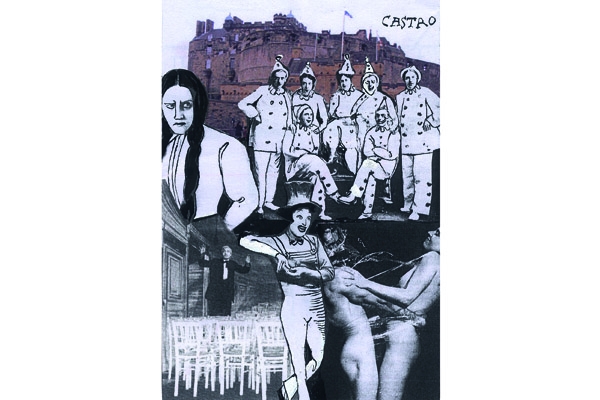

One of the rites of passage for a comedian is walking through the rain at the Edinburgh Fringe, looking down and seeing one of your own flyers being trampled underfoot. If you want a vision of the Fringe, imagine a boot stamping on a flyer of your own face — for ever. Or until the end of August, which feels much the same.

•••

Conventional wisdom is that flyers are the only way of making your show stand out. You can make the world’s best one-man production of The Mousetrap, but the world won’t beat a path to your door unless they’re handed a picture of your face and selective quotations from every review you’ve ever had. Selective quotation is an art form. It reached its apogee when the Scotsman gave the comic Jason Wood a one-star review and he emblazoned his posters with ‘A star — The Scotsman’. Some of the publications here make it too easy: Three Weeks is written by student journalists, who tend to write like students rather than journalists: thesis, antithesis, conclusion. It only takes a moment to eliminate the negative. When they described a show I wrote as ‘containing fleeting moments of genius, although most of it was only funny if you were drunk’, pressure of space meant that I could only use the word ‘genius’ on my flyer.

•••

Reviewers pick up on odd things. I have one line in my hour-long show about the Cameron administration — a silly joke about the coalition, which I follow up with a sotto voce, ‘Seriously though, they’re doing a grand job.’ (One for the comedy nerds.) A reviewer immediately wrote me up as the only Tory apologist on the comedy circuit. There are, in fact, more Tories on the circuit than you’d think — they just don’t talk about politics. (If they do, they take care to call themselves ‘libertarians’, a label that allows you to attack big government while still looking ‘edgy’.) This may be because the only comedy clubs that welcome political comedy nowadays self-define as left-wing. Lolitics in Camden, the most prominent at the moment, advertises itself as ‘a club for socialists, anarchists, liberals and lefties’. I occasionally drop into a panel show called The Comedy Manifesto in Edinburgh, and always lose by record margins after the chairman automatically deducts one million points from my total for being a Conservative.

•••

In practice, though, we are all free-marketeers. Comedy is the only art form which has no state subsidy to speak of, which is probably why it is currently thriving; and even the ‘Free Fringe’, whose propaganda claims that it is some kind of workers’ co-operative, is nothing of the sort. The Free Fringe is a strand of shows which are free to the audience because they’re in venues that are free to the performers. (The bigger venues can insist on payment up front of thousands of pounds, which is never recovered — a friend of mine is in a sketch group which was nominated for the Perrier, received excellent reviews and was sold out every night, and still lost £10,000 on the deal.) But if something is free, as they say on the internet, you’re not the consumer, you’re the product. Performers do shows for free to advertise their wares — the most popular shows on the Free Fringe are showcases, which are basically commercial breaks, five or more comics doing ‘trailers’ for their own show — and the venues, usually pubs, give them rooms free to drive beer sales. And there’s always a bucket at the end for donations. Although some comedians sneer at these shows — Andre King argues that if you do a free show, you’re not a comic, you’re a beggar with a gimmick — some high-profile acts are now doing the Free Fringe; they know the profit margins are higher.

•••

It’s more difficult being one of the few Christians on the circuit: again, the few comics that are ‘out’ tend not to talk about it on stage. (We occasionally meet for mutual support; we can fit comfortably in the snug of a west London pub.) And yet atheists bang on about it all the time: and always such easy targets. More comics have done material about the ‘God Hates Fags’ Westboro Baptist Church than there are members of the Westboro Baptist Church.

•••

Audiences are down this year. For the first couple of weeks, we told ourselves it would be fine once the Olympics were over but they haven’t bounced back. No one really knows what sells a show. Sometimes, it’s something as ridiculous as a good name. There was a show a few years ago called Silence of the Trams, a reference to the tram works, a city council vanity project which has been disrupting the city for five years, and it sold out despite mediocre reviews. The show in the next room to mine is called Britain’s Got Fuck All Talent, and is always packed, whereas I’ve been struggling to get audiences for my show, Born to be Mild, an allusion to a song written in 1967. Pop culture references are fine, it seems, but only if they come from the past 18 months. I am learning, though: my previous show was called Afternoon Men, which Spectator readers will immediately recognise as a line from Robert Burton’s 1621 masterpiece, The Anatomy of Melancholy. This still seems appropriate for a comedy show, I think.

Comments