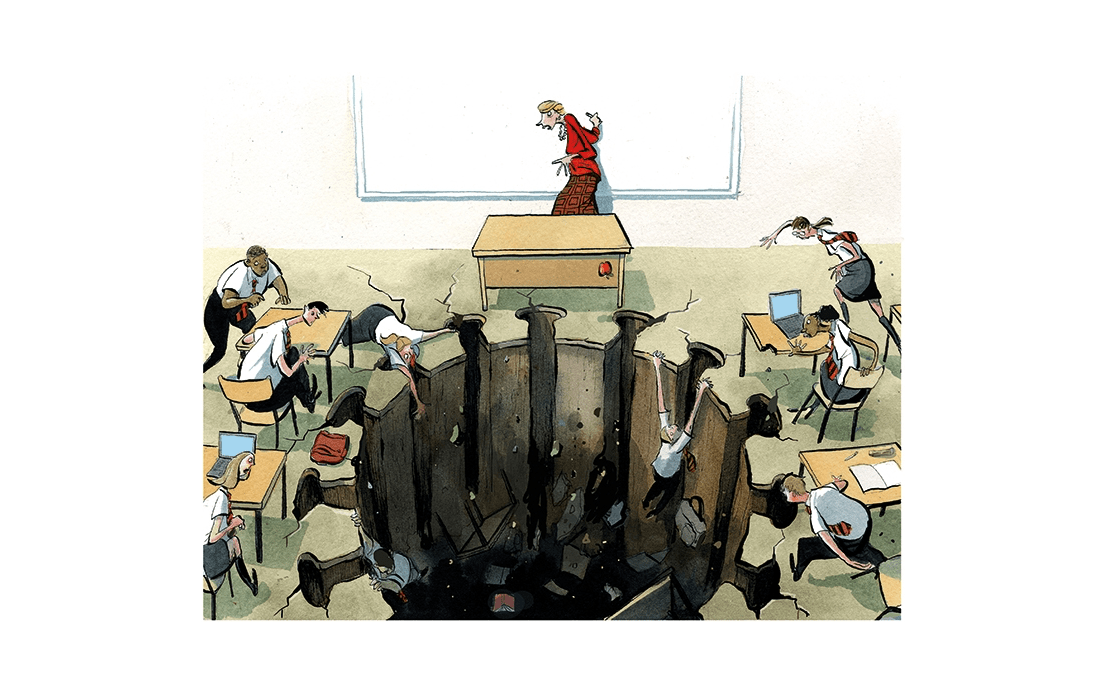

How can ministers stop one of the worst legacies of the pandemic being a generation of children left behind after a year out of the classroom? This week, when Boris Johnson confirmed 8 March as the earliest schools will return, he also announced money to help pupils catch up and a long-term plan for education.

There’s a glimpse of the scale of the task facing the government as it develops a long-term plan in this report from the Education Endowment Foundation, which found not only a significant fall in attainment for primary age pupils as a result of the disruption to the school year, but also a ‘large and concerning attainment gap between disadvantaged pupils and non-disadvantaged pupils’. The study, based on data collected from assessment in reading and maths taken in November 2020 by more than 5,900 year 2s in 168 primary schools, found a gap equivalent to seven months’ learning between disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged children. It could not assess how much the gap had grown by as a result of lockdown because it used data from 2017 that did not compare the performance of disadvantaged pupils with others.

Overall, pupils were making two months less progress in both reading and maths compared to children in year 2 in 2017. The report also found ‘a very large number of pupils were unable to engage effectively with the tests’.Helping pupils who are two months behind is no small task in itself. Closing an attainment gap of seven months for kids hit particularly hard by lockdown is another — and a small pot of money won’t cover it. As the Sutton Trust’s Sir Peter Lampl said in response to the EEF, work, ‘vast resources need to be targeted at disadvantaged pupils by raising the pupil premium significantly and providing funding for tuition’.

On today’s Week in Westminster, I interviewed Conservative chair of the Education Select Committee Robert Halfon and Labour peer Lord Adonis about what can be done to close that gap. Halfon has been calling for a ten-year plan for education, in the same way as Jeremy Hunt was able to secure a long-term funding settlement for the NHS when he was health secretary. Adonis knows a thing or two about big government programmes on education: he was involved in many of them under the Blair government.

Both argued that education would need to be one of the government’s priorities for the next few years if children are to have any chance. Neither were particularly gushing about the current Education Secretary Gavin Williamson. Whether or not Williamson is being fairly blamed for the chaos in his department over the past few months, it is clear that he does not have the political capital needed to pursue one of these big long-term programmes. Whoever takes over from him will need to be the sort of big political beast who can push the Prime Minister until schools have enough resources and support to close the gap. Education can’t be seen as a ministerial backwater from now on, far too much is at stake.

Comments