Experts warn that doctors like me risk a condition known as ‘compassion fatigue’ – an emotional numbness that comes from too much caring for too long. But aren’t we all on the edge? Distant hardships are now visible as they happen, and the sense that victims are everywhere becomes vividly real. Newsreaders, documentary makers, editorialists, politicians and campaigners imply we’re shallow unless consumed by the wretchedness they describe.

I meet the unfortunate, struggling and afflicted on my ward rounds. And I deal with those who have been made frail by age, bad luck and bad choices. Obstetricians get flowers and wine for helping bring wonder into people’s lives, orthopaedic surgeons for fixing hips and restoring freedom. I tend not to get gifts. Who thanks the person who diagnoses dementia, withdraws active care or treats an overdose?

I’ve learned not to take on other people’s misery. There are patients whose sadness is increased by all attempts at sympathy, and there are others, sunk in despair, whose hope returns at the merest hint of kindness. Many of my patients are lost in dementia, and a smile is the best response I can hope for. When I can cheer them up, I notice I am cheered up too, and when I fail, my spirits flag. As a medical student, working with a wise GP, I remember a run of soul-sapping home visits. Decay and dementia in one, the despair of chronic and destructive alcoholism in the next, and then a young mother, welcoming us to her warm kitchen – everything set for domestic happiness, save her terminal cancer.

When we left, the GP announced we would make one more visit before returning to the surgery. ‘She hasn’t asked us to come,’ he said, ‘but we can say we’ve come to check on her medication and she’ll cheer us up and give us cake.’ She did exactly that. Surprised to see her doctor turn up unannounced on her doorstep, she welcomed us in. I suspect she understood why we had come, just as I suspect that the lesson I learnt from the GP is part of why I survive the wards today.

‘Attend to the effects tea and coffee produce upon you,’ advised Sydney Smith. It’s good advice and it applies to more than hot drinks. There should be no limit to our sympathies, and we would be diminished if there were, but we should think about the effects of dwelling too much on some people. Does raging about Meghan Markle make us kinder? Does fretting about the stature of politicians improve our day? Does reading an article strengthen our interest in the world, entertain us, help us see a problem more clearly? Or does it consume our reserves of patience?

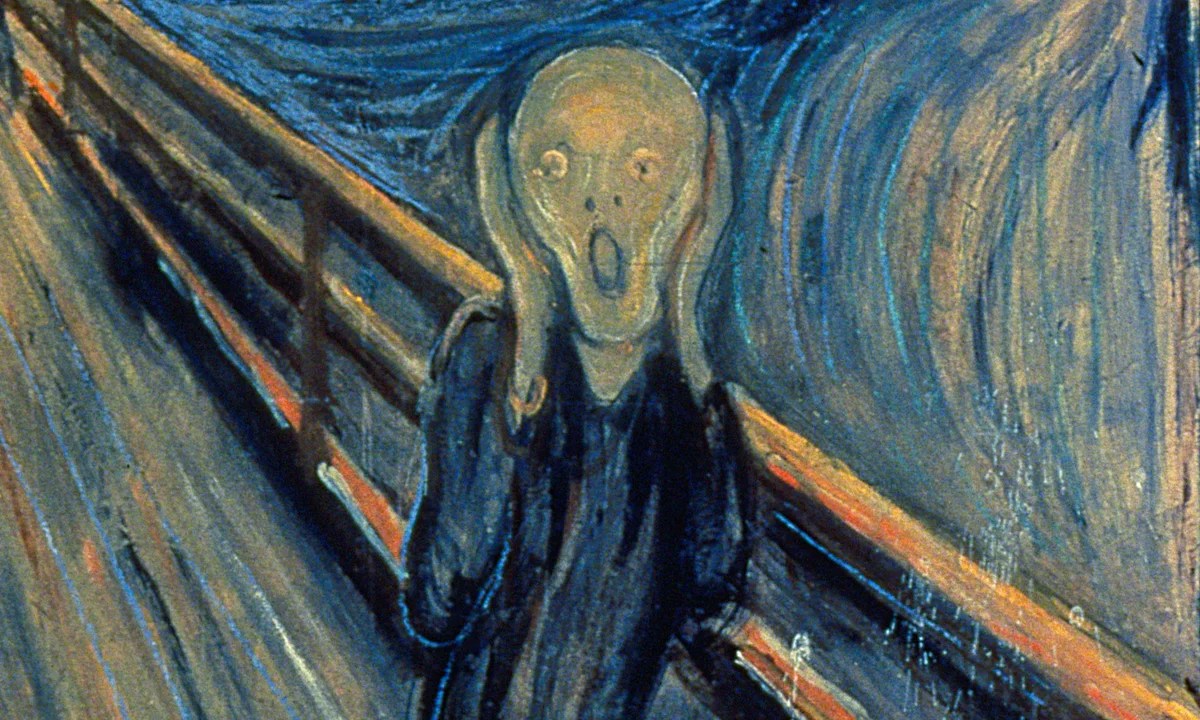

Today we get to see the faces of the murdered and the starved, to hear their final pleas in their own words, to see their experiences almost at first hand. Failing states and doom-laden elections make their way directly into our living rooms. The world’s traumas flood our thoughts and drown our happiness.

We are not made hungry by famine in Africa nor harmed by bombing in Ukraine

That the world seems close to doom is not new. Every age – from Napoleon to the Cold War to our screen-lit era – has its existential threats. It is foolish to believe they are not real because they take new forms, but ahistorical to think that living with them is a novel experience.

We have always fretted about matters beyond our own lives, worrying about affairs we are connected to only in our imaginations. So we should. Putin and Trump will rise and fall, shaping other lives, yet their direct impact on us – despite our worrying – is probably close to nil. We are not made hungry by famine in Africa nor harmed by bombing in Ukraine, but these events are the stuff of our world. We would be dull not to feel involved. Today, though, technology makes distant problems feel immediate – and when every tragedy demands our full concern, exhaustion creeps in.

Under this assault, it’s worth remembering that the world’s woes aren’t always ours – and that life, despite the constant gloom of current affairs, keeps its quiet glories. Orwell marvelled at a toad’s eyes, Yeats at the thought of Maud Gonne’s youthful embrace, and F.W. Harvey began his poem:

From troubles of the world /

I turn to ducks.

A well-lived life meets troubles without being consumed by them – especially those beyond our power to mend. Sane to grieve for a troubled world. A mistake to let it spoil your day. ‘The wise bustle and laugh as they walk, but fools bustle and are important,’ wrote F.L. Lucas, after serving in both world wars, ‘and this, probably, is all the difference between them.’

Comments