There is a lot to like about Diane Purkiss’s English Food. It’s a hefty thing, packed full of titbits to trot out down the pub, but also a serious consideration of how English food has changed over time, and of the perils of assuming there has ever been a golden age, or even a very stable one.

The layout is good, organised thematically rather than a chronologically, which saves the book from getting bogged down in repetition, and avoids the common trap of listing endless menus and foodstuffs. The best chapters are often the shortest. The one on apples includes a fascinating collection of facts, folklore and recipes, as well as a consideration of just how difficult it is to work with historic definitions. The section on codlins – a big or small apple? One that cooks to a foam? One intended for a specific recipe? – is almost worth the price of the book alone. When on a roll, Purkiss weaves together snippets drawn from across the millennia into a narrative that not only flows beautifully but is underlaid by a knowledge of the modern state of things and an understanding of what readers will be familiar with, be it myth, fact or what they find in the average supermarket aisle.

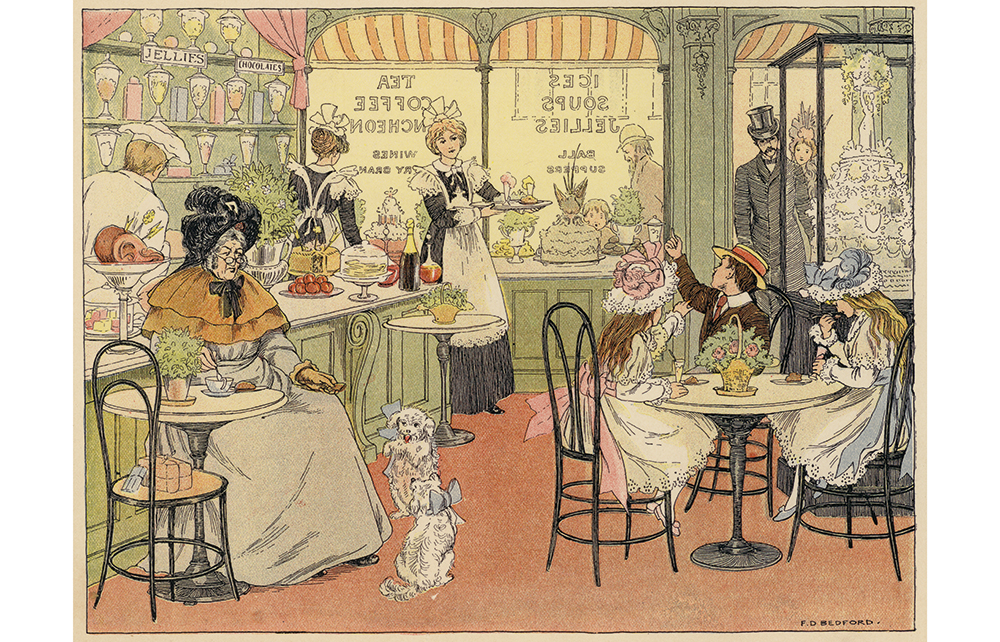

Other standout chapters include those on pigs, milk and tinned food, along with shorter essays on lunch and tea (the meal, not the drink). Purkiss’s forensic approach to source material is evident throughout, together with her refusal to be taken in by a tediously rose-tinted past; and her brisk rebuttal of the notion of authenticity in food made me want to punch the air with joy.

As might be expected of an English literature scholar, there are some brilliantly chosen quotations from a wide range of sources, far beyond the usual chestnuts trotted out in food history books. The thematic structure frees her to include material from prehistory, the classics, archaeology and the visual arts, as well as literature, which she does with skill and verve – shell middens and mosaics rub shoulders with 1980s TV adverts and Victorian bodice-rippers.

When Purkiss brings in the modern world, cross-comparing directly or simply making passing remarks, it elevates the book above what it might otherwise have been. Gently but firmly she points out that 19th-century nutritionists were as much swayed by the food industry as our modern equivalents, and that a self-sufficient Britain has always been a myth.

She is also refreshingly blunt about Elizabeth David (‘she saved English food, but did so by killing the Englishness of it’), and rightly acknowledges that Fanny Cradock was a far more influential figure at the time. And she fulfils her promise to talk about ‘the people’s food’, doing so with sympathy and balance. A key theme is the way in which patronising middle-class writers have often failed to understand the simple facts about being achingly, horribly poor.

There are, however, some missteps – though overall they make little difference. Beer was not always strong, and eggs were smaller in the late-18th century, so cutting down on their number when re-creating recipes of that period makes perfect sense. I’d liked to have seen more on the (much repeated) claim that everyone had such terrible teeth they had to eat purée all the time; and airy statements about historians having ‘set views’ on certain topics (e.g. grocers) grate.

There are also claggy chapters, such as the one on chicken – not an undeserving subject, it being the world’s favourite meat, not just our own. But in a book about English food, beef would surely have been a better choice – so long such a symbol of Englishness that, with plum pudding, it once represented the nation in speech and satire. Instead it is written off in a few paragraphs – as is curry, which might also have deserved a section of its own. Still, Purkiss concludes her chapter with a brilliant demonstration of why food history matters, weaving the past into the modern debate over chicken in a nuanced and sensitive way.

There are other anomalies. The chapter on cake feels cursory, though the importance of Twelfth Cake is overplayed. But more seriously, where is the discussion of sugar? One of Purkiss’s themes is the significance of empire, mainly in terms of how global tastes spread to English food, and she is clear-eyed in her descriptions of the atrocities carried out by the British abroad, and of how food became a tool both of oppression, and (to those who were eating it) civilisation. But as soon as the narrative seems about to lead on to the subject of sugar, it veers off in other directions. Thus we read (at the end of a consideration of liquid foods) that ‘without sugar, the diet of the poor, even today, would be mostly a matter of flavourless bread and water’ – and then turn the page… to find fish. A better use of the cake chapter would surely have been to tackle the subject of sugar, without which cake would not exist.

Overall, however, this is an excellent addition to the corpus of food history. The scholarship is impeccable, the prose highly readable and the topics mainly well chosen. Most importantly, it will make you think – and perhaps pause next time you are shopping or cooking. One to savour.

Comments