It is a common prejudice about modern politics that it is all focus groups and spin, all public relations and advertising. The rather heartening conclusion from Sam Delaney’s history of advertising in politics is that this is a calumny on the political trade.

Delaney has spoken to everyone involved in political advertising since the phenomenon began in earnest with Wilson in 1964 and can hardly find a soul who is certain that advertising does anything more than varnish good ideas. Maurice Saatchi, for example, credited Margaret Thatcher’s proposals, rather than his talent for a pithy slogan, for her electoral victories. Chris Powell, a leading figure in Labour’s Shadow Communications Agency, also doubts whether advertising can really change popular opinion.

The case in point, and the most gripping couple of chapters of Delaney’s account, are his accounts of the rival teams in the 1987 general election campaign. Under the inspired autocratic leadership of Peter Mandelson, Labour ran a stunningly brilliant media campaign. Mandelson’s central insight, true then and more so now, was that as party affiliation had declined, so the importance of the leader had increased. Hugh Hudson’s marvellous film, in which Neil Kinnock was lobbed soft questions by a young Alastair Campbell, showed the Labour leader at his oratorical best. His personal rating jumped 16 points after the broadcast.

Meanwhile, the Tory communications team was in disarray. Lord Young and Norman Tebbitt were fighting for control of the message. Tim Bell, who used to describe himself as the ampersand of Saatchi & Saatchi, had fallen out with the brothers, and the prime minister did not trust Michael Dobbs, who was ostensibly in charge. The team ended up in court, suing one another. The Tories won the election with an overall majority of more than 100 seats. As Tim Bell said, ‘We could have put up a huge poster in Piccadilly Circus saying fuck off and people would still have voted for us.’

Yet there is a counter-view, to which Delaney turns at once. The 1992 general election was a close call and it is plausible to suppose that presentation helped turn it. The Tories, as Chris Patten relates, started the campaign on tax, talked a bit more about tax and then concluded on tax. Yet it is surely true that the Tory ‘tax bombshell’ campaign crystallised a perception already held rather than created a fear from a handful of dust.

The other story in the book is unexpectedly sweet. Politicians routinely shy away from slandering their opponents. Michael Foot did not want to talk about ‘Mag the Knife’. Mrs Thatcher returned the compliment by refusing to countenance criticism of Mr Foot for being a pensioner. John Major hated being personal about Tony Blair.

In any case, politicians themselves are sceptical about the whole business of advertising. For many years, Labour politicians in particular wondered whether mass communication was even ethical. In 1983 Johnny Wright, who was running Labour’s advertising, went round to see Michael Foot to discuss which images to use. Foot spread the pictures out on the floor and when his dog Dizzy sniffed one he declared that was the choice and promptly went out to dinner. This was the same campaign in which Foot spent the first days bragging to Roy Hattersley about how he had once introduced Arnold Bennett to Lord Beaverbrook, which was interesting but hardly relevant.

Mad Men and Bad Men is full of tales like this and Delaney is an entertaining guide, but it is not clear whether we really get anywhere. This is a book that lacks a conclusion. In the epilogue Delaney says rather limply that ‘researchers say that there is no statistical evidence to show that exposure to advertising influences people’s voting choices. But that’s not really the point.’ Well, that is rather the point. That is the thesis that underlies the book, and if advertising does not matter then the book is no more than a curiosity.

The limits to what advertising can achieve are obviously severe. No presentation could have salvaged Labour in 1983. The ‘demon eyes’ posters did nothing to help the Conservatives pull Labour back in 1997.

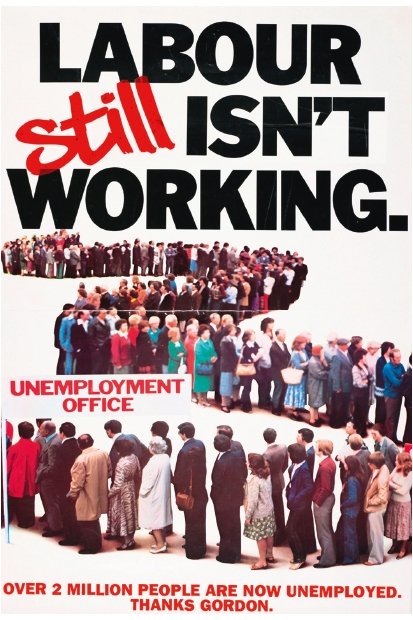

Callaghan did not think that the famous Saatchi poster ‘Labour isn’t working’ changed much. Maybe he is right, maybe he is wrong. At the end of this entertaining book we don’t really know.

Comments