James Forsyth reviews the week in politics

‘But has it cut through?’ This is the concern that nags at the Tories after every announcement. They know that they are winning the day-to-day battle in the media but they worry about whether this is making any difference in the country. They fret that the campaign, so far, is a piece of political drama for the political class and that the electorate are tuning it out.

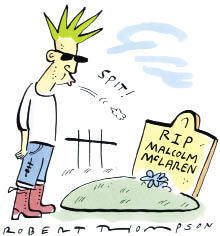

Those who return from the election frontlines to Conservative Campaign Head-quarters bring back the message that the voters are disillusioned. In the words of one shadow Cabinet member, they are ‘swimming against an incredibly strong current of anti-politics feeling’. If people don’t believe what politicians say anymore, then they will reach for the remote control when anyone with a rosette pops up on television. It is hard to win a political battle if your enemy is the ‘mute’ button.

This week, I visited two marginal seats that the Tories have to win to form a government. The first was the Labour-held seat of Dover and Deal. As is customary for political journalists who leave London, I quizzed the cab driver like an eager explorer asking questions of his Sherpa. His verdict was that he paid a ‘silly amount of tax on a tiny income’ — and said high petrol prices were causing him problems. If any party was going to change either of those things then he’d be interested, he said. But when I told him that the Lib Dems would help with the first problem and the Tories with the second, he was unmoved.

As I went round with a Tory canvassing team in Dover, I repeatedly encountered the same determination not to vote. According to the local Tories, Labour is losing plenty of votes. But about a third of these voters were switching over to the abstention party.

This disaffection isn’t confined to a narrow group or class of people or the supporters of any one party. My next stop was the Liberal Democrat seat of Sutton and Cheam. There, in a prosperous part of the seat, I met a woman who warned that lots of her friends were considering voting BNP because they wanted to send a message to the political class.

The Tory manifesto was based around a recognition that voters don’t believe politicians’ promises any more. Its central message to the electorate is that they are being asked not to transfer power from Labour to Tory, but from the state to themselves. To borrow Barack Obama’s phrase, David Cameron isn’t asking you to believe in his ability to change Britain. He’s asking you to believe in yours.

But Cameron is taking far more of a gamble than Obama. The son of a Kenyan goat-herder clearly represented change: the purpose of Obama’s line was to persuade people that his campaign was more than a cult of personality. By contrast, Cameron has yet to establish a decisive poll lead (the majority of polls still point to a hung parliament) because the public is not yet convinced that he is the change they need.

I understand that there have been four drafts of the Tory manifesto since Gordon Brown became Prime Minister, one for every time the Tories thought that Brown might go to the country. Each sketched out a picture of a Britain where the state pays for services but a huge panoply of organisations provide them. This idea is the fusion of the Blairite pro-market agenda, Burke’s little platoons and Friedman’s freedom to choose with a dollop of the internet revolution added. The whole cocktail is very Oliver Letwin and very Steve Hilton.

Samantha Cameron herself chose the shade of blue used for the cover of the Tory manifesto, grandly entitled an ‘Invitation to join the government of Britain’. Three questions present themselves: will anyone read it? will anyone understand it? and will anyone RSVP?

Labour’s public response was that the blue-bound book was an agenda of abandonment, that the people elected — and needed — a government to govern for them, to make choices for them. (Ironically, this was the line that the Brownites always used against the Blairite choice agenda, but on Tuesday it was Peter Mandelson who was trotting it out.) The more paternalistic Tory MPs agree. They snort that parents don’t want to set up a school but just want a good school to send their children to. The classic Conservative argument — that choice itself ensures the provision of good local services — is one that even some Tory MPs need coaching in.

The argument of the Tory manifesto is bold. For all the presentational brilliance of the launch, the manifesto is proof that the leader of the opposition is not just a PR man. He has chosen to inject a fundamental question about how Britain should be governed into the campaign: do we need an ever larger state or, if the state withdraws, will society expand? ‘It proves that DC’s not afraid to take a risk,’ as one insider puts it.

But even those of us who are inherently sympathetic to the ideas advanced in the manifesto have to recognise that they are not pub-ready. I’m informed that over the next few weeks there will be a major push to explain to people how their lives will be improved by the ideas in the manifesto. But this work has been left late. As with so many of the problems that the Cameroons have had since the start of the year, they are paying the price for things not done 18 months ago.

One thing that is not understood about the Cameroons is how serious some of them are about policy. It is easy to look at the Tory hired guns and the emphasis on tactics and presentation and conclude that winning is all they care about. But the manifesto shows the intellectually serious side to the project; the benefits of the policy trips to the United States, Japan and South Korea, the engagement with behavioural economists and the ideas that Hilton absorbed in his time in California.

At the beginning of the year, there was a divide in the Conservative campaign between those who wanted to make a positive case and those who wanted to hammer Brown’s record. The Tories are now doing both, as they should have been from the start. The benefit of this to them is, as one strategist explained to me, that while the opening political story on the news might be a typical he-said-she-said political spat, the second one shows them offering positive ideas.

Since the start of the campaign, we have seen a return to an earlier vintage of Cameron, the Cameron who declared ‘let sunshine win the day’. But if this message doesn’t cut through soon, expect to see the Tories placing ever more emphasis on the argument that the country can’t afford five more years of Gordon Brown. That is one message that is pub-ready.

Comments