No doubt Michael Gove is satisfied with how his latest comments on Scottish independence have gone down. The Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, de facto minister for the Union (even though that’s meant to be someone else’s job), told the Telegraph he couldn’t see any circumstances under which the PM would allow Nicola Sturgeon a second referendum on breaking up Britain. This is exactly what Scotland’s embattled unionists want to hear and seem not to tire of hearing, even though they hear it a lot. Sturgeon has obliged by accusing Gove of ‘sneering, arrogant condescension’, ‘completely refusing to accept Scottish democracy’ and helping ‘build support for independence’. And so on this dull, dishonest dance goes.

One of my more unpopular opinions is that Michael Gove is a good’un: a capable minister with intellectual bottom and an admirable gift for deviousness. These are necessary traits when contending with the Scottish nationalists, whose cunning, determination and political dexterity are still perilously underestimated by Whitehall and the London-centric right. He also penned two very good pieces on Tony Blair (one in the Times in 2003, the other five years later in The Spectator) that explained better than anyone else on the centre-right why Blair was such a capable prime minister — and explained better than many on the centre-left why Gordon Brown never could be.

Yet when it comes to the Union, Gove is unmistakably a Brownite. Not only does he attend the court of the gloomy Thane of Fife, seeking counsel on constitutional affairs, he oversees the continuation in government of important aspects of Brownite thinking on independence, the Union and devolution. Not least the doctrine that Scottish nationalism is a strategic problem that can be managed by a succession of tactical fixes designed to avoid, delay, ameliorate and appease.

The destination is decided; the only question one of pace

This doctrine is what lies behind Gove’s latest statement and the many more that have gone before and are yet to come. Ministers need to understand, however, that each and every one of these statements represents a political failure that, while appearing to outmanoeuvre the nationalists, in fact aids their cause. Not in the sense that Sturgeon suggests, of triggering Scottish thrawnness with imperious disrespect, but because it furthers the SNP’s narrative that independence is a living policy, a practical possibility — just one more heave away. The nationalists say an independence referendum is coming, the UK government says not yet. The destination is decided; the only question one of pace.

What are the voters of Scotland to make of this? From Holyrood, they hear that independence would see their children grow up in one of the wealthiest and fairest countries in the world, but that Westminster is holding them back. From Westminster, they hear the reasons they ought to be held back (‘once in a generation’, ‘recovery not referendum’, ‘now is not the time’), plus some pabulum about how the Union works for Scotland.

The UK government will get nowhere as long as it continues to fight on its opponents’ intellectual terrain and deploy the tactics of the people who got us into this mess in the first place. The problem is that neither the government nor the Conservative party has intellectual terrain of their own. Gove was a sound choice to spearhead the government’s pro-Union efforts, though the recently-touted Ruth Davidson could do a job of work for them too. (I previously suggested she should be put in charge of an advisory council on the Union.) But personnel doesn’t matter nearly as much as purpose, and it is that the government lacks. It knows why it is against independence but not why it is for the Union.

Almost a quarter-century since devolution, a Blair-initiated process originally opposed by most Conservatives, the Tory party has yet to develop its own theory of these constitutional arrangements. The SNP has a theory: devolution is a stepping stone to independence. Scottish Labour’s thinking is, predictably, more complicated, drawing in part on principle and in part on political expedience. Labour believes devolution is a) the democratic articulation of Scotland’s national distinctiveness, b) a strategic bulwark against independence, and c) the party’s most evident legacy in Scotland that must be defended for that reason.

The Tories lack a theory of devolution because they lack a theory of the Union. Tories are by instinct sceptical of theory and ideology but the muddle-along approach, particularly against an adversary that has a lucid and emotionally appealing objective, is hindering a pushback and any chance of victory over separatism.

A Tory theory of devolution would free the minds of ministers, MPs and MSPs, policy wonks and special advisers from received wisdom drawn from parties and ideologues hostile to a Conservative position on the Union. It would transform the way the government talks about the Union and in time the way pro-UK politicians in Scotland talk about it. Eventually it would change how voters in Scotland think about it. It would pave the way for policies aimed at defeating rather than diverting the SNP, at strenghtening and deepening the Union rather than ‘saving’ or ‘defending’ it.

The substance of such a theory is a matter for a longer discussion, but among the principles it should enshrine is that Britain is a unitary state; that sovereignty resides exclusively at Westminster; that devolution does not dilute or divide that sovereignty; that devolved legislatures and executives should concern themselves solely with devolved matters; that mandates on reserved matters cannot be obtained at elections to devolved bodies; that, having already devolved too many powers, there should be a presumption against devolving any more and open-mindedness about means for correcting that error; that there is no lawful route to secede or hold a referendum on secession save by an Act of Parliament; and that the ever-weaker Union model, in which devolution serves as a one-way ratchet to independence, should be replaced by a policy of ever-closer Union.

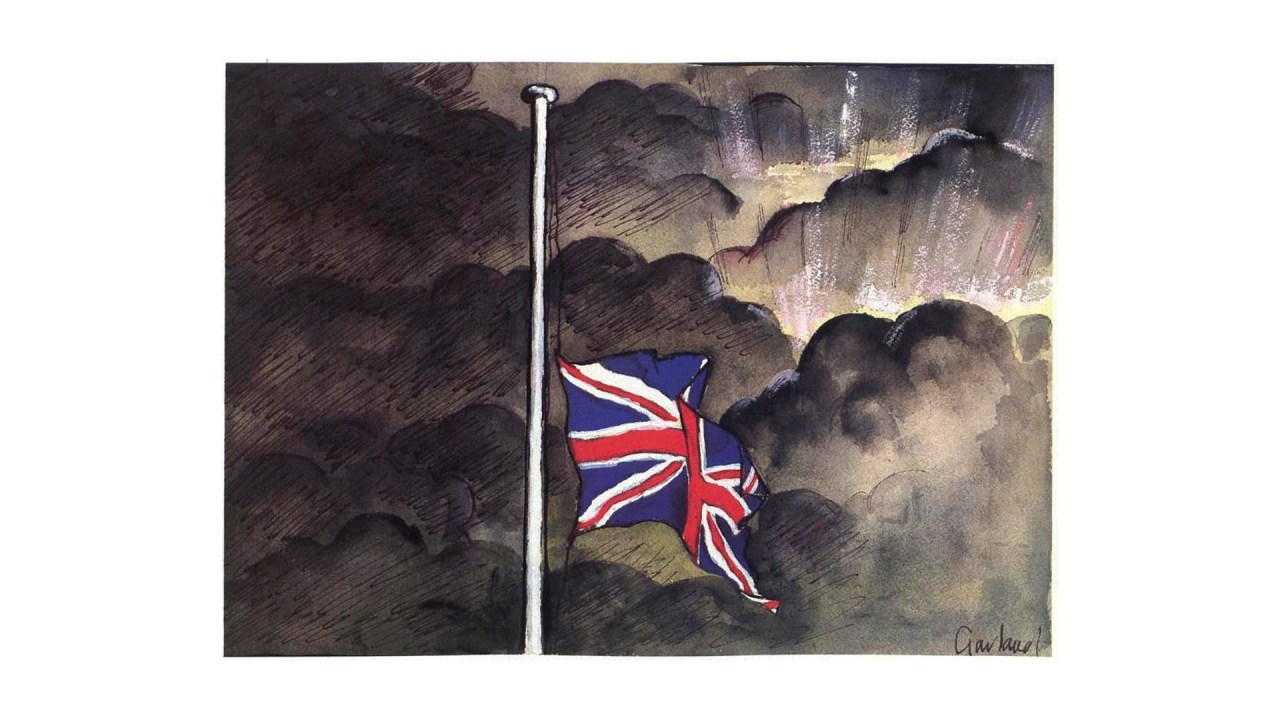

A Tory party that espoused these principles would secure the very Union that allows political and cultural differences to flourish across Britain. What inhibits devolution is its hijacking by ideologues bent on parlaying these differences — differences that all countries contain — into separatism and their (mis)use of the institutions of devolution to achieve it. Remove, or greatly reduce, the threat of secession, while accepting that doing so will entail the expending of much political capital, and you may slowly begin to open up a space for post-constitutional politics. Sink independence as a near or medium-term possibility and, once the din dies down and the smoke clears, the SNP will be left to thrash around for another electoral buoy. It may even have to start running Scottish schools and hospitals half-competently.

Michael Gove needs to stop being the Minister for Not Yet and become an advocate at cabinet for placing a steely, confident, optimistic unionism at the heart of the government’s constitutional policy.

Comments