It’s unusual for musicians to become writers. The trajectory of yearning is meant to be the other way around. When I was a teenager working at the New Musical Express I was bemused by the number of men there who had won the greatest prize on earth — being paid to write — but nevertheless dreamt only of being crooning cretins, singing the same songs over and over again. The fact that Chrissie Hynde (who once, pre-Pretenders, tried to recruit me to a biker-themed girl group, telling me that my stage name would be Kicks Tart) had once been their colleague only served to fuel the poor suckers’ self-delusion as they banged away cluelessly, ignoring the somewhat pertinent facts that — unlike them — their erstwhile office mate happened to be a brilliant singer, songwriter and sex bomb.

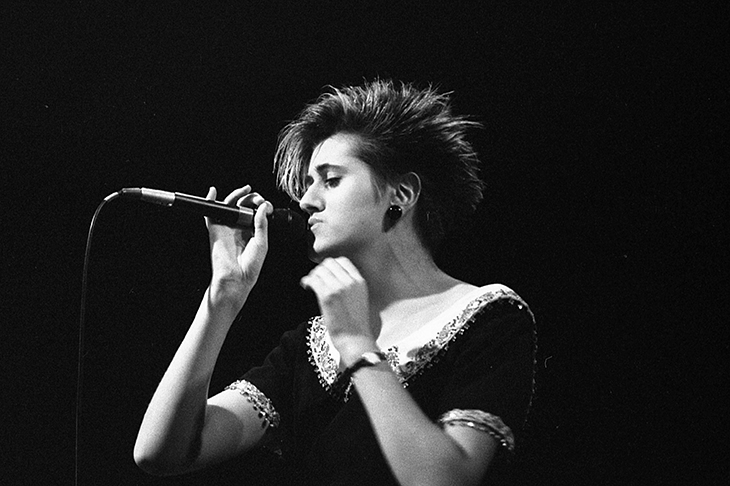

Chrissie has now given it up to be a painter; Lauren Laverne (broadcaster) and Louise Wener (novelist) also used to be in pop groups. And then there’s Tracey Thorn, co-founder of student favourite Everything But The Girl, whose 2014 book Bedsit Disco Queen: How I Grew Up and Tried to be a Pop Star was a smash hit and who’s now a columnist for the New Statesman. It’s interesting how male musicians don’t do this. Is it seen as ‘stepping down in the dominance hierarchy’, as the psychologists have it?

An agreeable feature of Bedsit Disco Queen was that the adolescent Thorn had written a song about me, the imaginatively titled ‘Julie’ (‘Everybody hates you, Julie/Everybody hates you but they can’t see/What you’re really like, Julie/ Everybody hates you — except for me’), which I found out about in the most delightful way. In my sleep I heard someone say my name and woke to hear Thorn repeating it on the radio. Of course I’ve been biased ever since, but you really wouldn’t turn your back on a musical career that had seen you sell more than nine million records if you didn’t have a pretty good idea you’d be even better at the next thing. And the gamble has certainly paid off.

It’s as though Mr Pooter and AdrianMole had had a test-tube baby, as Thorn alternates between excerpts from her teenage diaries and modern-day musings on the meaning of suburbia — in her case the Hertfordshire commuter village of Brookmans Park. Her experience was so like mine (and I grew up in the bustling city of Bristol) that I do wonder whether what she suffered from was more about being in the 1970s and not being in that London than it was about being stuck in the suburbs. Everything’s relative; I remember a girl starting at my junior school whom I considered the epitome of cosmopolitan glamour because she came from Sidcup.

Memoirs are whodunnits for people who mistrust tidy endings, and this book is as fascinating for what it leaves out as for what it allows in. You can see the seeds of EBTG’s fervent evasiveness in entries such as ‘Tried to go to the library but it was shut’; and ‘Went to Welwyn to get some boots but couldn’t get any’.

Then, just when you’re getting comfortable with this charming but inconsequential absence, the big reveal — or rather conceal — happens. Thorn recalls being bullied at school but does not mention it once in her diary, which, given the amount of ‘getting off’ with older boys she details, was surely intended for her eyes only. Or was it? Was she already practising to be a pop star? Did she want her parents to read it and scold her for being a wayward minx rather than to see her as a child in need of parental protection?

Thanks to the internet, no western teenager nowadays has any excuse for thinking they’re the Only One Who Feels Like This unless they’re determined to. Indeed, it might be argued that youngsters are now overkeen to identify as outsiders, if we consider the way various sorts of self-harm spread like wildfire in adolescent friendship groups. But this is a double-edged sword. Thorn is not the first person to put forward the notion that boredom sparks creativity, so with the cornucopia of entertainment available, no wonder youth music is such rubbish these days. Still, if I’d been able to choose between brooding creatively or sexting mindlessly I know what I’d have preferred to spend my Fruit Salad Chews days doing, and it wasn’t the worthy option.

I am wary of confessional writing, associating it on the one hand with misery memoirs and on the other with humble-bragging. And I can never rid myself of the suspicion that most alleged guts-spillers are fibbers. I don’t mind people lying to me one bit — it can be entertaining stringing them along, pretending to believe them — but if I suspect they’re lying to themselves, I check out.

This tender-hearted, tough-minded book seems set to revivify a genre that can too often be self-deluding and thus pointless. And now she’s a proper published, brilliant writer, I can finally admit I could never stand Tracey Thorn’s singing voice all along — ‘Julie’ or no ‘Julie’.

Comments