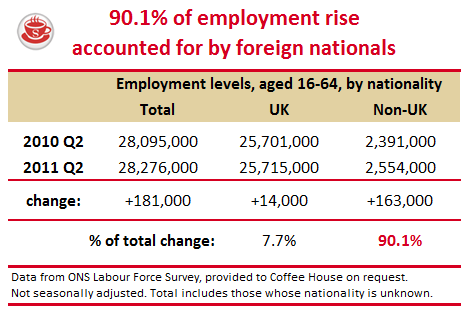

George Osborne was right to boast in the Commons that Britain has the “second highest rate of net job creation in the G7”. Coffee House recently pointed out that all of the increase is accounted for by foreign-born workers. But what if you narrow the definition to foreign nationals? We put in an information request to the Office for National Statistics and the below information came back. It is quite striking. Over the 12-month period to which Osborne refers, 90.1 per cent of the extra employment amongst the working-age population can be accounted for by an increase in foreign nationals working in the UK. Here are the figures.

The phenomenon of pensioners returning to work is fascinating, but separate. The government’s aim is to move people from the unemployment register and into work: this is a battle fought amongst the working-age population. So that is why we asked the ONS to produce figures focusing on this.

I have blogged a fair bit about immigration, and for a reason. The trajectory of this recession is teaching us plenty about the dynamics of economic recovery in the 21st century. The number of foreign nationals working in Britain has almost trebled since 1997 – the border is not an obstacle. Britain has something that Keynes could never have envisaged: a truly globalised workforce in which new British jobs are as welcome in Gdansk as they are in Glasgow. Norman Tebbit’s post-riot exhortation to ‘get on your bike’ and find work is now obeyed by Poles who get on the overnight bus. And who can blame them? Industrious immigrants are hardly the villains of this story. Without them I seriously doubt the jobs Osborne talks about would be all filled by Brits. We’d just have fewer jobs, smaller economy and a duller country.

Osborne has a chance to advocate a fresh approach to job creation. He can argue that Britain’s problem is not a supply of jobs. His recovery has provided plenty, as he says, yet still the dole queue lengthens. Britain’s problem is a supply of workers. An unusual concept, but governments can increase the supply of workers by cutting taxes and therefore increasing the incentives to work. The Universal Credit, which Osborne planned jointly with IDS, will help. But it’ll take the best part of a decade to pull off. So meanwhile, something more crude – emergency tax cuts for the low-paid – would be the most effective stimulus that Osborne can offer. Sure, it might cost. There’s plenty of fat in government budgets to cut. Other countries’ experience with tax cuts for the low-paid suggest at least half of the ‘cost’ is recouped, due to lower welfare costs and more wealth creation.

I’m not saying that the government is in denial. IDS does talk about foreign nationals taking most jobs under Labour and admits it’s getting “worse now”. But if welfare pays more, why work? It doesn’t help to talk about “benefit cheats” being “leeches on society” as Osborne did yesterday. The Chancellor should instead ask why so many millions stay on benefits. The answer is that the government he now runs spent the last 20 years paving the way towards welfare dependency. It’s easy to insult people as they walk down that road. But it’s more constructive to build a new road, out of benefits and towards work.

Today, we read that a security firm in Coventry advertised 20 vacancies and received just two applications – in a city with 10,700 supposedly “looking for work.” If the firm fills those 20 posts with immigrants, can anyone complain?

Either you can say this shows Brits are lazy (as a surprising number of MPs do, in private) or you can argue – as I do – that the problem lies with a tax-and-benefit system that needs reforming. And urgently. As the above figures show, Osborne is presiding over what is – for British citizens – a jobless recovery. The penalty for this is usually paid on election night.

Comments