It is nothing short of a miracle that this aptly titled exhibition could be shoehorned into just two rooms at the Royal Academy, such was the range of the irrepressible Hugh Casson’s work and influence during his lifetime. Architect, artist, designer and writer, he was a fireball of energy and a fount of ideas. He was described by one friend as ‘the golfball on an IBM typewriter’. Not the least of his multifarious talents was, indeed, making friends with anyone, from the casual visitor queuing for the RA’s latest exhibition to the Queen and Duke of Edinburgh, for whom he worked discreetly but tirelessly for many decades on a series of royal apartments, unaltered to this day. He carried the theme of friendship into his presidency of the Royal Academy (1976–84) by establishing the Friends of the RA, who now number more than 100,000 in the UK — there are many more in America — and who underpin the Academy’s finances to a crucial degree.

Many will recognise the charm and dexterity of Casson’s sketches and watercolours: John Betjeman said that he sketched just as most people hummed, going about their daily lives, but he was hardly encouraged in this at school: ‘Art was what a thick boy did on a wet Wednesday afternoon,’ he recalled. He depicts himself, comical, bespectacled and faintly bemused, in many of the letters and ephemera on display, and his facility as a draughtsman undoubtedly eased his entry to his chosen career as architect. He joined the modernist practice of his former Cambridge tutor Christopher (Kit) Nicholson in the mid-1930s, and was invaluable in his work as a camouflage officer during the war. His ingenious schemes convey the delight he took in devising convincing disguises for the portable RAF hangars sited on secret aerodromes, just as he had relished painting sets for student productions at the Cambridge Festival Theatre.

His career really took off in 1951 with his appointment as director of architecture for the Festival of Britain. At 40, he was astonishingly young and relatively inexperienced for such a prestigious post — architectural commissions after the war had been thin on the ground — and a less ebullient character might have been intimidated. However, it brought out the impresario in him, as well as a flair for choosing talented individuals to work with and persuading them to do much more than they ever thought they could — a talent he perfected over the decades. Additionally, he was a natural radical, and the sketches for his own contributions to the Festival site show his boldness of vision. The result, a triumph for the revival of postwar morale (as a very jolly film makes clear), earned him a knighthood and crystallised his reputation; his subsequent partnership with Neville Conder at Casson Conder and appointment as professor of interior design at the Royal College of Art, combined with considerable charisma and diplomatic skills, brought him an endless stream of high-profile commissions.

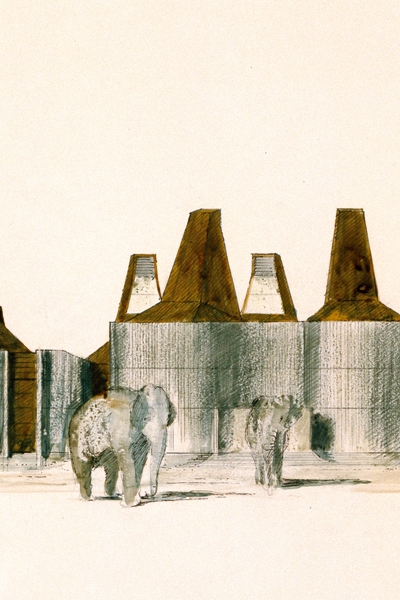

The many schemes on display, from the elegant modernism of his beach house for Lord Montagu of Beaulieu to the high-spirited fantasy of his Coronation decorations, show Casson’s infinite flexibility of response: he combined a deep seriousness about the importance of design with a playfulness that was to find its apotheosis in his pièce de resistance, the Elephant and Rhinoceros Pavilion at London Zoo — now home to some unusually privileged Bactrian camels.

His tastes were omnivorous, undoctrinaire and open-minded: he would extol Victorian architecture in one publication while advocating prefabrication elsewhere. What mattered to him was effective design of high quality, and the many demands from all quarters were fulfilled only by dint of hot-desking at the office long before it came into vogue. His set designs for Glyndebourne and the Royal Opera House, his Midwinter pottery ranges, postage stamps and wine labels are all on display, along with pages from sketchbooks, travel journals and letters — he could never resist a marginal illustration, and his thank-you letter to Prince Philip for the latter’s 50th birthday party forgoes text entirely in favour of a series of gloriously colourful vignettes of the high life, to which he was unabashedly partial.

Casson’s fervent belief in modernity and change — that without change comes atrophy — underlay his extraordinary energy and verve. This show runs alongside the RA’s Summer Exhibition, and in comparing the architectural schemes across the corridor with his of 50 years before, one suspects that he would have relished their novelty and imagination.

Comments