Andrew Solomon’s simple and powerful guiding idea in this book is that there are two sorts of identity that affect your place in the world. Your ‘vertical identity’ is what you share with your parents — and it usually, but not always, includes such things as race, religion, language and social class. Children are born with ‘horizontal identities’ too — which is to say, things that they don’t share with their parents but that they have in common with others elsewhere: being the deaf child of hearing parents, the schizophrenic child of mentally well parents, or the gay child of straight parents.

Some of these horizontal identities are things that are, or were, regarded as impairments; some of them are understood as mere difference. With many, that question is precisely the one that’s up for grabs. Do we choose the ‘illness model’ or the ‘identity model’: seek to fix the condition, or seek to accept it? Early on, Solomon quotes Jim Sinclair, an intersex autistic person, putting a forceful case for the latter:

When parents say, ‘I wish my child did not have autism,’ what they’re really saying is, ‘I wish the autistic child I have did not exist, and I had a different (non-autistic) child instead.’ Read that again. This is what we hear when you mourn over our existence. This is what we hear when you pray for a cure. This is what we know, when you tell us of your fondest hopes and dreams for us: that your greatest wish is that one day we will cease to be, and strangers you can love will move in behind our faces.

The project of Far from the Tree is to find out about how a whole range of horizontal identities actually work in families and the wider world: how parents cope with them, how children feel about them, and how they negotiate the institutional, social and sometimes medical worlds in which they participate.

Solomon has what you might call ‘skin in the game’. The first chapter, as well as eloquently setting out his stall, describes Solomon’s own experience as a son with three horizontal identities — homosexuality, dyslexia and depression — the difficulty his parents had accepting his gayness. The last chapter talks about his own experience as a father (first by IVF with an old friend; then through surrogacy with his husband): ‘I started this book to forgive my parents and ended it by becoming a parent.’

Solomon writes very well and has done a mind-boggling amount of work. He reports having 40,000 pages of interview transcripts, and this thumping great volume is not so much a single book as a library, each chapter dealing with a different circumstance and then, within that, dealing with a splintering of sub-identities. Part of its provocation is that the people in any given chapter will often resent the implied comparison to those in others.

As he writes in his opening chapter:

All people are both the objects and the perpetrators of prejudice […] My mother’s issues with Judaism didn’t make her much better at dealing with my being gay; my being gay wouldn’t have made me a good parent to a deaf child until I’d discerned the parallels between the deaf experience and the gay one […] Many gay people will react negatively to comparisons with the disabled, just as many African-Americans reject gay activists’ use of the language of civil rights.

And everyone, it seems, feels entitled to find dwarfs funny.

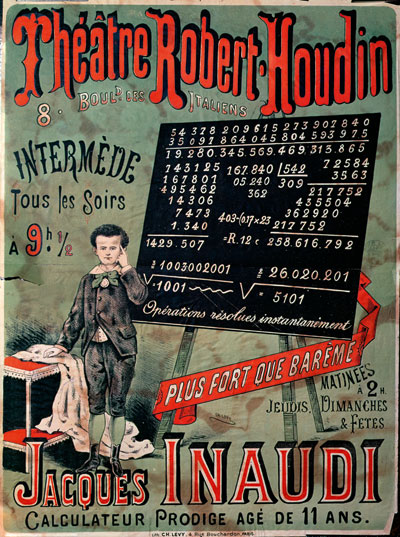

There are chapters on deafness, dwarfism, Down’s Syndrome, autism, schizophrenia, transgender issues and disability. But there is also one on prodigies — parenting a prodigy, Soloman reports, can be every bit as difficult and estranging as parenting a disabled child. There’s an extraordinarily complex and harrowing chapter on children conceived in rape. And, perhaps most controversially, there’s a chapter on criminality — in a dry joke that also serves as a telling reductio ad absurdum, Solomon writes that: ‘For people disabled by inherent moral perplexity, we offer not support but imprisonment.’

For a long time, the crude arguments between left and right on certain sorts of difference have been that, say, criminality is volitional whereas short stature is not. Gay-rights activists have made headway with the slogan ‘Born This Way’ — but there’s equally well an argument that if you want to sleep with another man, how dare the straight world expect you to beg permission on the grounds that you can’t help it? One form of homophobia has it that even if afflicted with such urges it’s your responsibility to fight them; another has it that it’s ‘a disease’.

Solomon gently, lucidly, unemphatically and unanswerably shows how much more complicated it is than that. Since the advent of cochlear implants, let’s say, you can make an argument that, sooner or later, not being able to hear will be a matter of choice. But whose choice — given that neurology dictates that to be effective the implants need to be placed in childhood? And what of those deaf identity advocates who argue — though not all in such strong terms — that to eliminate deafness would be a genocidal assault on a language community?

We all feel queasy about eugenics. But as we are able to screen for ever more birth defects, the political and ethical issues around abortion get more pointed. Likewise, the availability of treatments for some of these conditions changes the landscape in which they are understood: ‘social progress is making disabling conditions easier to live with, just as medical progress is eliminating them.’

There’s frequently a double-bind. If you are determined to understand your horizontal identity as difference rather than disability, that risks cutting off your chances of benefiting from disability legislation or funding. And the choices individuals make have an impact on others in similar conditions. When it comes to deafness, for instance,

The problem is that those who do not get implants may be seen as having ‘chosen’ their condition in the face of a ‘cure’, at which

point they do not ‘deserve’ the ‘charity’ of taxpayers.

Solomon is not out to bang a drum for any particular point of view. He’s simply outlining the arguments and reporting — sometimes grimly, sometimes inspiringly — on the different ways that families and individuals manage these issues. There are often fierce differences within these communities, after all, as to how they should be approached and understood.

And Solomon certainly isn’t the sort of extreme relativist for whom there is no such thing as disability. He tends to side with the psychiatric establishment when it comes to the ‘Mad Pride’ movement, for instance, which encourages schizophrenics to refuse medication and revel in their condition. Likewise, he gives short shrift to the ‘pro-ana’ websites that encourage anorexics to celebrate their identity by starving themselves to death.

His aim seems to be to bring sympathetic common sense to bear, to allow lived experience to trump theory, and let human beings, in all sorts of circumstances, tell their own stories. Nobody could read this extraordinary, moving book and not feel enlightened, but above all enlarged by it.

Comments