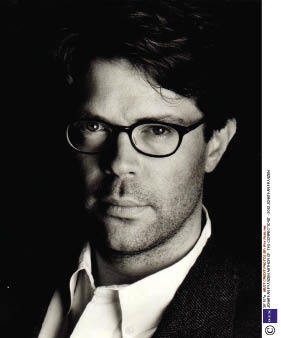

Philip Hensher salutes ‘Freedom’, Jonathan Franzen’s latest great American novel

Family is the engine that drives the novel. Relationships which are both fixed and constantly negotiated are what the novel, as a form, is about. We don’t choose our siblings, our parents, our children, but from day to day we choose, with the full volition of our existence, how those relationships will shape us. The interplay between our free will and the world which is wished upon us is the core, irreducible territory of the great novels. Perhaps now that family ties are growing more dependent on volition and goodwill (or bad) rather than on duty and obligation, family is becoming more of a fruitful territory for the novelist’s investigations, rather than less so. Certainly in this stupendous, magnificent, unforgettable novel, family has never seemed a more urgent and gripping subject.

The Berglund family are caught at the moment when a once edgy neighbourhood has moved indisputably into respectability and even smugness. In Minneapolis, their neighbours are generally, like them, professional, socially concerned and well-behaved. In the 1990s, this street is a kind of Democrat Valhalla. The four of them — Walter, his wife Patty, their children Joey and Jessica — are so typical that they come in for a ribbing from some very similar families. Only the more irregular ménage, such as Carol’s next door, reminds everyone that this was not always a middle-class neighbourhood. Their Volvo-driven concerns have every appearance of urgency. ‘Were the Boy Scouts OK politically? Was bulgur really necessary? Where to recycle batteries?’ English readers may be reminded of the Stringalongs, or of Posy Simmonds’s deathless Webers.

But the Berglunds are not quite as idyllic and admirable as they seem. Joey, at a startlingly young age, seduces the working-class Connie, whose mother, Carol, has taken up with the dreadful Blake. It seems quite easy for Patty to embark on passive-aggressive conversations about Blake’s long evening DIY sessions — ‘Hey, you know what, that Skilsaw’s pretty loud for eight-thirty at night.’ Curious, too, that all four of Blake’s tyres are found slashed one morning. When Joey actually moves in next door, the ethos of the family seems on the verge of crumbling.

After a masterly, tumultuous opening chapter, the question of where all this comes from is addressed in an extra- ordinary and lengthy document written by Patty for the benefit of her therapist. We hear about her disaffected and cruel family; an early rape; a bizarre and painful friendship between the sporty basketball star that was Patty and a drug-fiend called Eliza. Into this mix has come a memorable, laconic, rather brutal boy called Richard Katz — ‘Basketball star. What are you — forward? Guard? I have no idea what constitutes tall in a chick.’ He has, too, a sweet, perhaps slightly dull friend called Walter, who of course will rescue Patty. (‘He always started yawning about 9 p.m., which Patty, with her own busy schedule, appreciated when she went out with him.’)

Walter and Patty debate, from the start, the question of what it means to be ‘genuinely nice’, with the counter-examples of Richard — ‘he’s actually very unpleasant to be around’ — and Eliza close at hand. It’s one of the most resonant and masterly aspects of this novel that both Walter and Patty have themselves their unpleasant aspects. Walter, like many liberals, is committed to a view that the world has too many people in it, and also too many of the wrong sort of people. As the novel proceeds, their joint unpleasantness remains uneroded, while, unexpectedly, sustaining our sympathy and interest.

Patty’s testimony, in all its untrustworthiness and frequent small-mindedness, becomes a crucial document as the plot unfolds. (‘In these pages, the autobiographer here acknowledges her profound gratitude to Joyce and Ray [her parents] for at least one thing, namely, their never encouraging her to be Creative in the Arts.’) At one point, Joey fails to finish Ian McEwan’s Atonement, another novel in which a woman’s written document becomes an object of intense narrative interest.

But as the lives of the Berglunds diverge, fall apart, hold precariously together in a world of money, political beliefs and sexual obsession, we never feel that we are at the mercy of a playful novelist, but just of a great observer of life.

‘I know essentially nothing about sex,’ Walter confessed.

‘Oh well,’ she said. ‘It’s not very complicated.’

This cruelly ironic note is struck frequently in the novel, as we see the many ways in which sex is, indeed, very complicated, wreaking havoc in everyone’s lives. The rogue element here is Walter’s friend Richard Katz, a cult rockstar, who has no truck with niceness and who sweeps through the family like a firestorm. ‘You play a very entertaining game,’ Walter observes innocently, of Katz’s chess. ‘I never know what’s coming.’ That game is revealed by the all-seeing narrator, however: ‘A navigational beacon in Katz’s black Levis, a long-dormant transmitter buried by a more advanced civilisation, was sparking back to life.’

The McGuffin of the plot is an extraordinary pseudo-ecological plan, master- minded by Walter and funded by a billionaire, to preserve the habitat of a small bird called the cerulean warbler. This Mephistophelean pact with coal-mining enterprises will be at the cost of destroying several thousand acres of mountain habitat, thereby creating some ‘sustainable’ employment for the atrocious local yokels in West Virginia:

Coyle Mathis’s philosophy of life was back the fuck off or live to regret it. Six generations of surly Mathises had been buried on the steep creek-side hill that would be among the first sites blasted when the coal companies came in.

Franzen’s satirical fury is at its height in the pursuing of this scheme, which acts as a front for Walter’s long-held ambition to campaign for population shrinkage: ‘I mean, presumably you guys aren’t advocating infanticide.’

But the mesmerising heart of the novel lies in Franzen’s unflinching and psychologically flawless expansion of the lives and passions of his central characters, through which history flows like a river. The one failure here is with Lalitha, Walter’s Indian-born assistant and (briefly) mistress, whose life doesn’t fill out in the same way as every other character, and who for me remained a useful agent of plot and no more.

Everywhere else there are almost Thackerayan riches. Joey’s appalling plan to make a million by selling rusting auto parts to the US government for its doomed campaign in Iraq is balanced by an unforgettable scene in which he rifles through his own excrement in an Argentinian bathroom for his swallowed wedding ring as his mistress bangs on the door. The satirical disdain can be strong, and alights unexpectedly and without restraint — on Jessica, for instance, saying of Lalitha that

years ago, when I first came down here, I asked her if she could teach me how to do some regional cooking, like from Bengal, where she was born. I’m very respectful of people’s traditions.

When Joey rediscovers his Jewish roots, persuaded by an enthusiasm for his best friend’s hot sister, the laughter may be scandalous. (‘Dude. Are you familiar with the Holocaust?’)

What is remarkable is that this sardonic edge to the novel doesn’t reduce the depth and range of its understanding and sympathy, which extends even to the point where Walter is finally glimpsed engineering the abduction of a hated neighbour’s cat.

Some commentators have remarked on the e xtent of the acclaim that this novel has received in America, and compared it with other, relatively neglected, novels of family life by American women novelists. I agree that most of the best American novels seem at the moment to be written by women — Annie Proulx, Jane Smiley, Lorrie Moore. Not all, however. And it is not detracting from them in the slightest to say that a novel as witty and rich as Freedom, as unprejudiced and interested in its approaches to existence, as bold and sage and moving, would always have been cause for celebration. A great American novel is unmistakably what Freedom is.

Comments