Our age isn’t the first to set an English landscape of our dreams against the one which actually exists, or see earning a living from the land as something base and destructive. The tension has always been there between people who work the land and the utopian dreamers for whom every mark of the plough is a scar.

Farmers bristle at talk of countryside utopias and rewilding, and passionate wilders can’t see why land managers do things which they think are harmful to the land. Both groups complain about being misunderstood by the other, all the while failing to spot that the much more profound threat to the countryside comes from those who don’t care about what happens to it at all.

The National Forest in the Midlands, like the Knepp estate in Sussex, which has become renowned as the birthplace of British rewilding, has come to stand as an icon for the positive possibilities of change. Having spent time in both, and met the people who have shaped them, I think that’s fair.

The most profound threat to the countryside comes from those who don’t care what happens to it at all

But we can’t use them as easy answers for every difficulty to do with state of our countryside. There are good farmers and bad farmers, and bad farmers have often been the product of bad public policy and the pressure to produce cheap food. That can change – and is changing.

Take Lee Schofield’s heartfelt new book Wild Fell. The strapline on the front cover, ‘Fighting for nature on a Lake District hill farm’, sums it up. Not all farming is toxic. Even rewilders should be able to admire the survival of the cultural tradition of Herdwick sheep farming in the Cumbrian uplands.

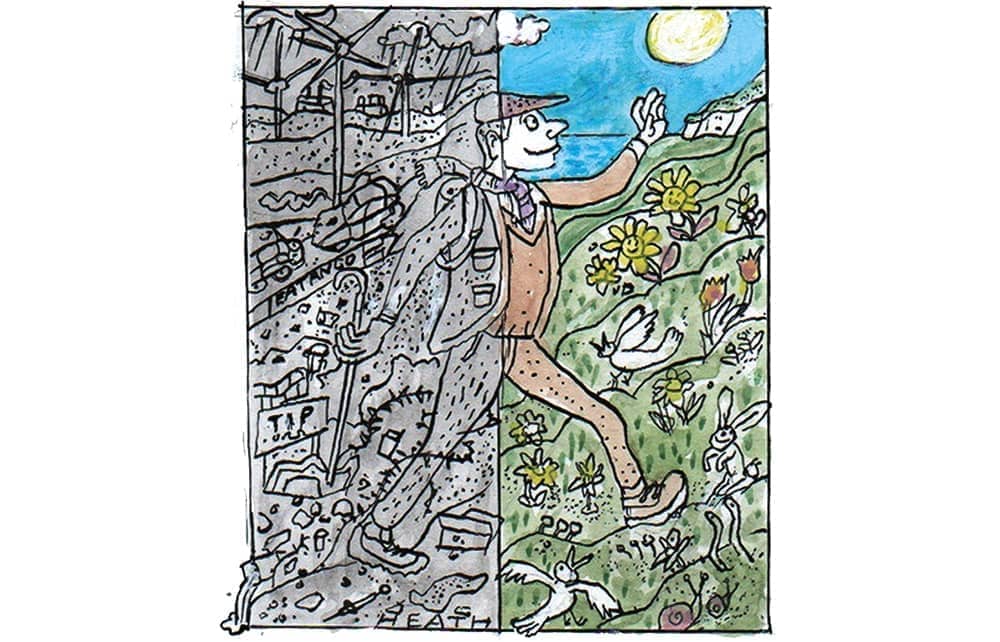

Read Schofield and make up your own mind. His story of managing the land around Haweswater, in the eastern fells, is compelling: by taking the pressure off the fells, with fewer sheep, and none in places, plants such as bog myrtle, valerian and devil’s bit scabious, which ought to grow freely, stand less chance of being chomped by livestock. I can remember walking once in north-west Scotland and crossing into a patch of mountainside, fenced off from deer, which was alive with flowers and insects, and the contrast with the grazed land outside was like moving from black and white to full colour.

Schofield wrestles with the implications of what he is doing for the farmers who make up his local community. He’d like them to understand that he’s not against farming, just the way farmers have come to behave after subsidies encouraged them to fill the hills with as many sheep as they could find. It wasn’t like this a century ago, he says, and he’s probably right.

But something he doesn’t mention stands out from the examples of good practice he sets out, such as Haweswater and Ennerdale,in the west of the Lakes. Haweswater was stripped of its population by the Manchester Corporation, when it dammed the valley in the 1930s for a water supply; Ennerdale, never much populated, was wrecked by the Forestry Commission around the same time. These are not classic farmed landscapes full of people. Change here is easier to organise – or impose – because of it.

Bringing about natural recovery alongside farming in other parts of the Lakes, let alone all of England, can’t be done by decree. It’s going to take concession and compromise and moderation and accepting failure as well as success, and these are not fashionable values in politics, or on social media where much quick opinionising about the fight over the countryside now takes place. It’s easier for strident campaigners to put a picture of a dead buzzard or an unhappy-looking cow on Facebook and count the clicks of their outraged vegan followers.

Schofield ends his book with a description of how he would like Hawes-water to be in 2045, when – he hopes – he will retire. It’s an idyll every bit as seductive as the ones set out by Shakespeare or English landscape painting. ‘The sheep are taking advantage of the shade beneath a large spreading oak, one of many that stud these fields. A pied flycatcher darts into a hole in one of their broad trunks, a beak full of grubs for hungry chicks.’

It’s what I would like to see in 2045 too: who wouldn’t? But the question is how to get there. ‘Spending time both with the Lake District’s farmers and with conservationists made me realise that we all have far more in common than divides us,’ Schofield writes. ‘The desire to become a farmer or the manager of a nature reserve is driven by the same things: a love of the outdoors, passion for a place to which we are connected, and the desire to shape and steward it.’

To that, some farmers might add what he misses: a sense of respect for the traditions of what they do, and pride in doing something which feeds everyone else. Those sheep on the hills exist to be shorn and eaten.

Conservationists would do well to understand this better and talk about it – as some do, Prince Charles among them. In return, farmers should admit that not all of them are good guardians of the land, or even good at their job, as the sad sight of a lane running with water mixed with raw slurry not far from where I live suggests. But that means not taking sides.

Comments