‘I have had more direct clinical experience than almost any other forensic psychiatrist of assessing and managing lone-actor perpetrators of massacres,’ writes Paul Mullen, professor emeritus at Monash University in Australia, in his introduction to Running Amok.

He’s got non-clinical experience, too. In 1990, when he lived near Aramoana in New Zealand, he was disturbed by gunfire one night. It turned out that the neighbour of one of his patients was busy killing 13 people. Afterwards, Mullen supported the survivors and his patient, who felt ‘anguish’ at not spotting the red flags to prevent the massacre. Mullen summarises what she told him about the killer:

His mood was marked by elements of despair and anger, which were sometimes manifested in statements about the pointlessness of life and the maliciousness of so many people. I now know that this information should have rung alarm bells; but I didn’t know this then, and nor did anyone else.

Since then he has assessed many ‘lone-actor mass killers’, as he terms them, including a man who shot and killed 35 people in Port Arthur, Australia, in 1996. When Mullen began his examination two days later, the killer asked: ‘I’ve got the record, haven’t I?’ Mullen certainly has the expertise; but what he didn’t have was social media clout.

This is the first book to be published by ‘not-for-profit’ Extraordinary Books, whose founder, Robert Silman, said of Mullen: ‘Despite his unmatched expertise and jaw-dropping experiences, expressed accessibly and lucidly, no publisher was willing even to consider his work, due to his lack of a social media following.’ So Silman created a company and published it himself.

The result is a fascinating and shortish book into which Mullen crams decades of knowledge. It begins with a brief history of lone-actor mass killing, going back to the 16th century in the Malay Peninsula, when young men ‘ran amok’ in public spaces, killing people at random with a spear or axe, until they were overpowered and were themselves killed – which was their aim:

The frequency of these events attested to the attraction for despondent, despairing young men who felt rejected and humiliated by those around them of a form of suicide that was not an act of withdrawal and defeat but one of heroic personal assertion and vengeance.

Mullen then starts building his case for how to prevent modern massacres, using the example of the way the ‘British colonial administration’ solved men running amok in the 19th century in what became Malaysia. Police were issued with long-handled tools to pin offenders against a wall or constrain them with a steel hoop. Courts then sent them to a psychiatric hospital, rather than to be hanged. ‘In a stroke, “shameful incarceration” was substituted for a supposedly “honourable death”,’ Mullen writes, leading to the ‘virtual disappearance’ of running amok.

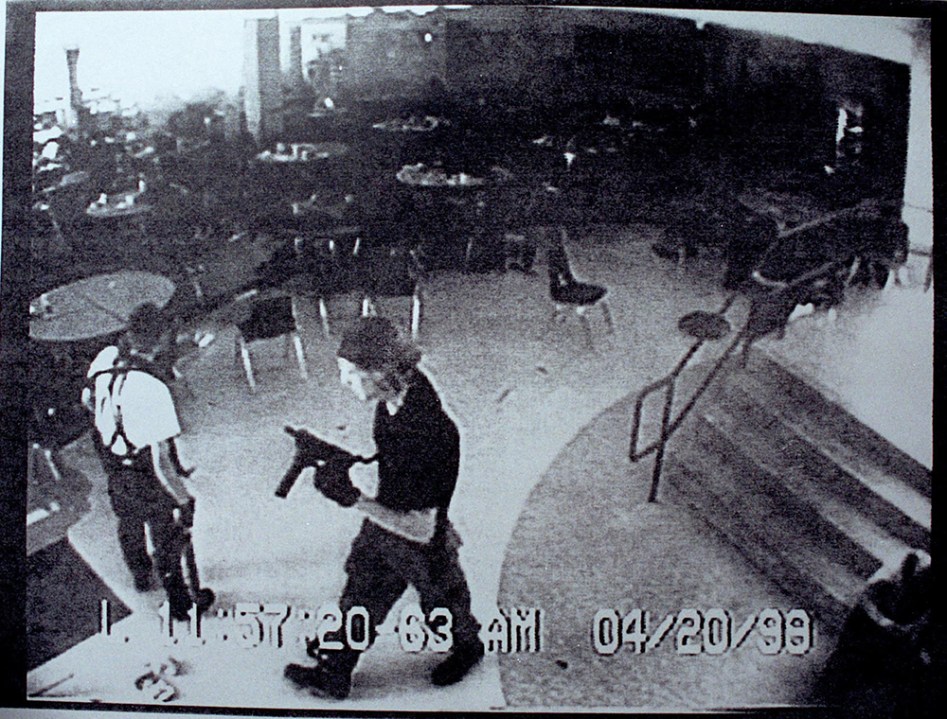

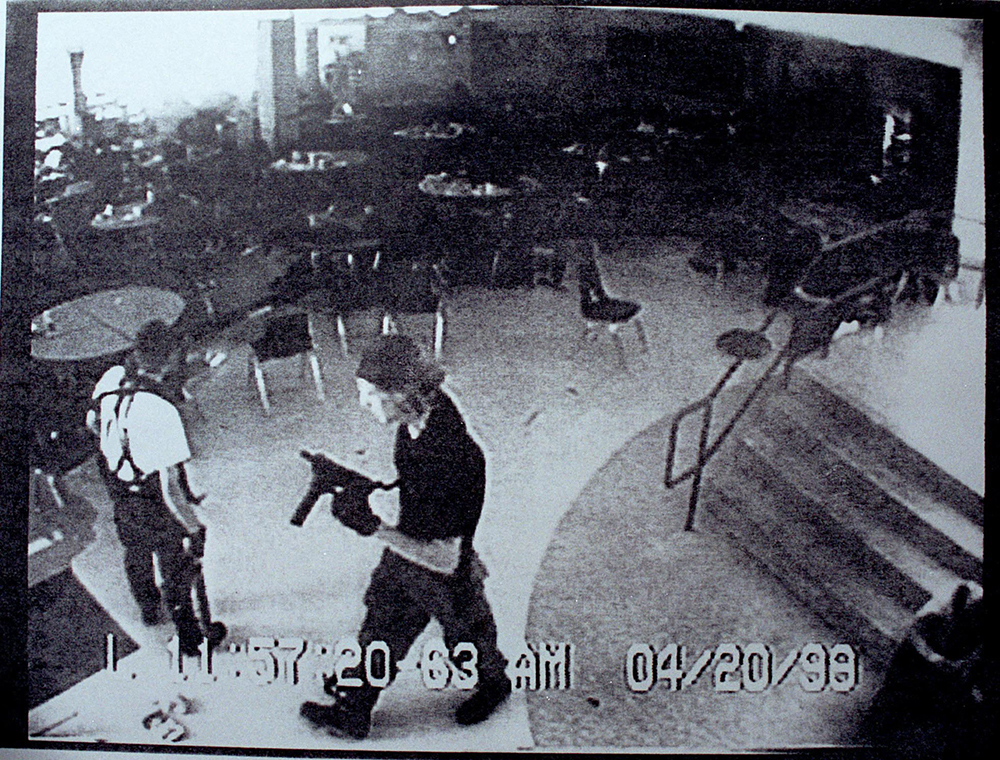

Most of the book comprises incidents from the past few decades, with Mullen describing his personal interaction with some perpetrators. But he also analyses some of the world’s most infamous massacres, including Dunblane, Virginia Tech and Columbine, the school where 14 people were murdered and which provided a blueprint for other horrors. How to avoid that contagion is one of the book’s main messages: ‘The media provide the fame these killers crave, and the publicity for their claimed justifications.’

Mullen avoids using the names of the killers throughout. Instead you get lines such as: ‘The Utoya killer’s parents were an ill-matched couple’; and the father ‘continued contact with both his sons at least until 2010, when the future Sandy Hook killer decided to break off all further interaction’. While reading, I repeatedly picked up my phone and googled to find out their names and to look at their faces. I don’t know why, but I wanted to see them.

In 2016 I wrote a book about a mass shooter from Northumberland. I’ll follow Mullen’s rules and not name him, but he described himself as ‘the Birtley gunman’. His name is in the title of my book, his photograph on its cover, and it includes many of his words. I doubt it sold enough to cause contagion, but Mullen’s book, because of the depth of his experience, is a very convincing argument that I was wrong.

The Birtley gunman actually spoke about the impact of contagion. A month before the Birtley shootings, another British man shot and killed 12 people in Cumbria. The Birtley gunman saw media coverage and in a recording while on the run described it as ‘a sign from God’. Since then, many British men have used the Birtley gunman’s name when threatening police or partners.

But while Mullen’s campaigning is convincing, it’s his analysis of the killers’ psychology that is most enlightening. One man, whom he interviewed over the course of decades, shot and killed seven people in Melbourne, and then said: ‘You’re not laughing at me now, motherfuckers!’ Being slighted is a running theme. There are few people as dangerous as an insecure man being laughed at.

Comments