What if you could pay £20 a year and get two good new books in return, with your name printed in the back of them?

It sounds good to me, which is why I’ve just subscribed to And Other Stories, a new independent publisher that operates in this collaborative, subscription-based manner. By essentially paying for your copy of a book before it’s printed, you help to enable the whole process. Brilliant for all involved.

This is an interesting model for And Other Stories to have chosen because, while it seems so revolutionary, in actual fact it’s surprisingly similar to publishing’s traditional set-up. The big publishing houses also operate on a subscription basis — known in the industry as ‘subs’ — but their subs are with booksellers rather than individual readers. And whereas the traditional system of subs seems to be in some ways very flawed, a similar system for And Other Stories seems to be nigh-on perfect.

It all boils down to trust. By subscribing to And Other Stories I am trusting them to invest my money wisely; I trust them to give me some good books in return. So far, And Other Stories seem pretty trustworthy. Their books are smartly designed, get great reviews, and one has even been shortlisted for two prizes. They are a small team dedicated to publishing good contemporary fiction. I feel like I’ve put my money in good hands.

Indeed, reading Down the Rabbit Hole by Juan Pablo Villalobos — the twice-shortlisted book — only confirmed my opinion. It’s quirky, edgy, off-beat, funny and very endearing. The story is told by Tochtli, a Mexican boy, who loves hats, samurai and longs for a Liberian pygmy hippopotamus. His childish naiveté proves to be a charming idiosyncratic filter to the very adult world he inhabits — he is part of ‘the best and most macho gang for at least eight kilometres’, lives in a ‘palace’ and knows rather a lot about killing people. Above all it’s a surprising book. Like Alice in Wonderland, to which the title alludes, this is a world where the improbable becomes probable, albeit in a very sinister way. I ended it and thought that I’d love to subscribe to future books published by And Other Stories, so swiftly signed up.

But I’m not sure I’d give £20 to a big publisher. Aside from the fact that that sort of money would get lost between the cogs of such a large machine in a matter of seconds, I think the major players are less trustworthy in terms of quality.

Yes, ok, when HarperCollins announces the publication of the new Hilary Mantel or Random House the new Robert Harris, readers know they’re getting a good book and booksellers know they’re going to sell masses of copies. These names are big brands. I trust HarperCollins with the next Hilary Mantel. But it’s different when the book isn’t written by a big name.

The traditional publishing subscription system works as follows: Big publishing houses send sales reps out to bookshops to pitch books three months in advance of their publication. The booksellers then tell the reps how many they’ll ‘sub’. Big publishers can publish thousands of books a year so it’s not unusual for a rep to pitch a hundred books at a time. They whizz through them on snazzy powerpoint presentations and, while the bookseller can say yes to twenty Hilary Mantels very easily, it’s much harder to discern from less than a minute of measly marketing points along the lines of ‘will appeal to readers of One Day’ whether or not a debut novel by an unknown writer will be any good. This is where the publishers are let down by size and lack of trust. If a sales rep is pitching twenty debut novels just in September, among a diverse plethora of history, classics and popular science books, they can’t possibly expect the bookseller to believe that they’re all brilliant.

Consequently, the bookseller subs either none or perhaps one copy. This gets back to the publisher, who becomes depressed, and wonders why he or she bothers to publish debut fiction. This feeling worms its way into their strategy for the coming year, and lo and behold, it becomes harder and harder for new novelists to get published.

The problem is: so many publishing houses have become monoliths. In an attempt to gain greater market shares, the big ones have eaten up more and more of the little ones. They allow them to keep vestiges of their original identity by being their own imprint, but, frankly, few people outside of the industry have a clue what an imprint is. A small publisher might gain stability, marketing spend and sales strategy and all the rest of that corporate-speak by merging with a big one, but they lose so much independence and trust. For instance, I would certainly trust Chatto to publish a really fantastic book, but they’ve been part of Random House for twenty-five years and it’s rare that you hear or think of them as a separate entity. Certainly their titles are just a few amongst thousands that are pitched by the same Random House sales rep who pitches books from commercial imprints like Vermillion and Virgin.

A small, nimble publisher, full of integrity, really can do things differently. And Other Stories are only publishing four books a year. All of them are new novels. Making sure they’re all really good is what they live for. So I believe them when they say they’re all brilliant.

And while independent publishers might not have the financial clout of the big houses — the marketing spend that will pay for a place in WHSmith’s Top Ten or for ads on the tube — to people who really care about good books, this trust and integrity is more valuable. If this is the future of publishing, then these are exciting times.

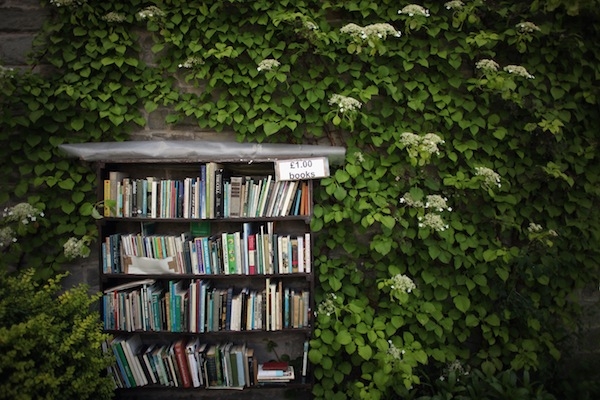

Emily Rhodes works in an independent bookshop. She blogs at Emily Books and tweets @EmilyBooksBlog

Emily Rhodes

Fiction by subscription

Comments