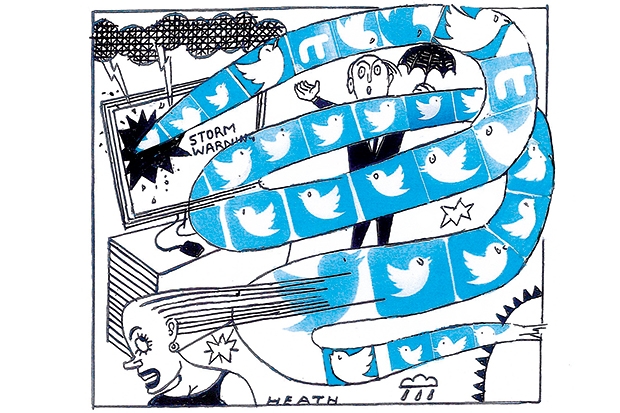

What should be the response of politicians to mass emailings and Twitter storms? The question is an urgent one, especially for Conservative MPs, given the general truth that mass petitions, in which complex issues are simplified to ‘for or against’ and emotion given a head start over reasoned argument, tend to come from the left. I was astonished to learn that a Tory MP decided his vote on the proposed Hunting Bill would depend on opinion polls in his local newspaper. In the event the Bill was withdrawn, largely, if Nicola Sturgeon is to be believed, as a result of online petitioning.

Progressive causes such as the campaign against hunting have a familiar profile: the powerless against the powerful, victims against oppressors, the clean utopia against the murky reality. Such causes make an email campaign look innocent: numbers, the campaign insinuates, are all that we — the powerless, the victims, the oppressed — have got.

The lesson of history, that mass movements threaten freedom, is a lesson that will never be learned. This is why we have parliaments, with their complex procedures, committees and reviews. Parliaments exist to inject hesitation and circumspection into the legislative process. And when we think about it we all agree this is a good thing. We all agree that the common good, rather than mass sentiment, should be the source of law, and that the common good may be hard to discover and obscured by crowd emotions.

However, tempted by a ‘one-click’ response to a complex question, people can be persuaded to add their voice to campaigns designed to bypass argument in the interest of a foregone conclusion. Invariably the conclusion has the beauty and simplicity of a final solution to some problem that affects us all.

The dangers here were apparent to the framers of the US constitution. They recognised that reason must triumph over passion whenever enthusiasm threatens to take control. The amendments to the constitution were therefore designed to protect minorities and dissenters, to prevent the emergence of factions and to ensure that those with the capacity to intimidate their fellow citizens would not have the advantage. Without such provisions, they thought, conflict could at any time sweep away reasoned government and the rule of law.

Conservative MPs should also take note of the great speech given by Edmund Burke to the electors of Bristol, in which he distinguished representation from delegation. The MP represents the interests of his constituents, not their opinions. And he represents those interests through a process designed to issue in laws that contribute to the wise government of us all. The representative does not sit on the benches of Parliament in order to jump up at every opportunity and repeat what the voters told him to say. He might well decide that the voters are ill-informed or moved by some passion that should, in their own interests, be overruled or discounted.

We can all see that this is so just as soon as we imagine mass campaigns being mounted for causes repugnant to us. Do we think that our representatives should be influenced by a Twitter storm advocating the expulsion of the Jews? Do we think that issues like the death penalty, the treatment of refugees, or the decision to send troops to Syria should be decided by a mass vote of internet addicts? We vote people into office because we feel confident in entrusting them with decisions that we have neither the expertise nor the capacity to make for ourselves, but which are nevertheless fundamental to our collective wellbeing.

The effort to understand what this involves, and what institutions would best serve the cause of representative government, occupied John Stuart Mill and Alexis de Tocqueville. Both of them sounded warnings against the ‘tyranny of the majority’, pointing out that minorities must be protected by a wall of rights if they are not to be persecuted in the name of democracy. Both believed that bills before the legislature must pass through a ‘committee stage’, as in the Westminster parliament and the Washington congress. When sitting in committee, members should be encouraged to consider the issue for its own sake, and with a view to reconciling the many interests that have a stake in the legislation. Members have a duty to ignore pressures from outside, and to consult those with the relevant expertise.

It would be a foolish MP who decided to ignore public opinion. But public opinion is not a monopoly of those who strive their utmost to mobilise it. The silent, the hesitant and the deferential have opinions too, and, as the last election showed, there may be a lot more of them than there are of the vociferous crowds who capture the attention of the media. Moreover, public opinion in a democracy is not a matter of the preparedness to say yes or no to some simplified question posed on a website. It is the result of a process.

What the people think is not necessarily given on the spur of the moment, or prior to deliberation. Public opinion emerges from the broad currents of argument and reflection among people who are ready at any moment to defer to the facts and to acknowledge the right of others to disagree with them. It is precisely through such institutions as Parliament that public opinion finds its voice, and to think that petitions on the internet are a reliable guide to what the people think is to make a profound mistake about human nature. We are not creatures of the moment; we do not necessarily know what our own interests are, but depend upon advice and discussion.

It is, of course, hard for the Conservative party to insist that its new intake pass a philosophical literacy test before joining the list of candidates. Nevertheless it ought not to be too much to ask that every aspiring MP read what Burke had to say about the office of a legislator. And it is surely right for every parliamentarian to know why Mill thought that the protection of minorities is more important for the proper functioning of democracy than the ability to transcribe vociferous opinions into law.

Comments