If you take the Tube to Colindale on the Northern Line and then hop on a 303 bus or walk for ten minutes, you arrive at the Royal Air Force Museum, open daily from 10 a.m. until 6 p.m., admission free. The place is full of planes, as might be expected, and has a wonderfully relaxed atmosphere (not nearly as frenetic as the Imperial War Museum) and a feeling of spaciousness. The Museum also mounts temporary exhibitions, and the one that drew my attention is of the pastel portraits of Eric Kennington (1888–1960), a war artist in both world wars, and an incomparable draughtsman, interesting painter and tough, inventive sculptor. The exhibition has been curated by the Kennington expert, Dr Jonathan Black, who has written a substantial and densely informative catalogue (£19.99 in paperback), with detailed entries for more than 100 individual pictures, to accompany and commemorate this display.

The Art Gallery is on the first floor, most easily accessed via the Conference Reception entrance, and is a large, dimly lit room with a couple of standing display cases containing uniforms, model aeroplanes and medals, and an array of Kennington’s pastel portraits around the walls. They’re all framed behind glass (which is essential to protect them) but the visitor is prevented from approaching them too closely by a safety barrier. The reflections on the glass (evidently non-reflective museum glass is too expensive an option) make them difficult to see from a distance, and the experience of viewing them would be greatly eased if the unnecessary ‘safety’ barrier were removed.

Kennington is rightly regarded as a supreme draughtsman, but are these works drawings or paintings? The colour and modelling has all the authority of painting, and though the pastel medium is essentially a linear one, Kennington’s approach is almost sculptural in its convincing three-dimensionality. The artist himself acknowledged this, explaining how he worked all over the surface of the paper at once and drew the head ‘as if it were a piece of sculpture in semi-darkness lit from a single source’. Many of the portraits loom powerfully out of the dark in this fashion, but others are placed against lighter grounds, a very few suggesting a specific setting. As John Brophy wrote in his book Britain’s Home Guard (1945), illustrated by Kennington: ‘He composes colour and shape into designs which satisfy the eye, and more than the eye. The effect is sharp, vivid, immediate, but it is an effect which reverberates in the mind, extends and subtilises itself, so that a picture which, at first sight, delivers a simple and direct message, later reveals, as it grows familiar, many auxiliary intimations of its purpose — and yet without losing its first unity and force.’

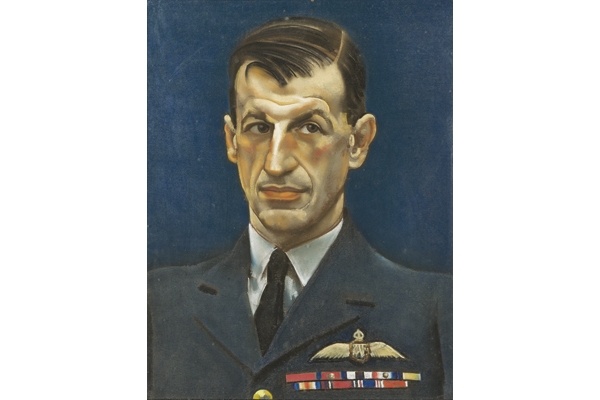

The drawings are hung all round the room in a single line, their visionary realism making an extraordinary impact on the unprepared eye. These are powerful images, from the lantern-jawed Flight Lieutenant John Colin Mungo-Park DFC, to the more homely portrait of Sergeant Hampshire, 6th Battalion, Middlesex Home Guard, depicted in his front room wearing full uniform. Notice the heavy but effective dusting of light (yellow pastel) on the uniform of the first soldier in ‘Home Guard Anti-Aircraft Gunners’. A comparable image is ‘Coastal Defence Searchlight’, lent by the family of the artist. A particularly striking portrait is the carved-looking likeness of Air Chief Marshal Sir Charles Portal, which involves a certain amount of heroic idealisation, but is none the less effective for it. In quite a different mood is the remarkable allegorical pastel of the severely burned pilot Richard Hillary. Entitled ‘The Heart of England’, this depicts the figure of the young airman in the sky over England, reaching out a bandaged hand holding a red rose towards our green and pleasant land.

The carefully judged emotion of this image is exceptionally potent, and I know of nothing like it in Kennington’s work, except an equally unusual pastel called ‘Resurgence’ (not in this show), depicting three medieval knights going to war in the flooding, multicoloured luminescence of a dawn sky. And there are other pictures here, besides the portraits, which pack a punch. For instance, the woodland setting of ‘Nissenland’, the intriguing snow-draped shapes of ‘Tanktown’, the electric jellyfish of ‘Parachutes’ and the large red exploding cauliflower of ‘Stevens’ Rocket’. But it is the succession of portraits that really carry the exhibition.

Examine the unflinchingly square jaw of Wing Commander Beamish, a famous boxer and footballer. Kennington commented of this sitter: ‘First, last and all the time a fighter. He stopped sitting for me at 11 a.m. to lead a squadron on a daylight raid: destroyed two Messerschmitts, machine-gunned four flak-ships and harried troops on the ground, then continued the sitting at 3 p.m.’ As Kennington later observed, ‘I’ve come to the conclusion that the great dignity these chaps have comes from their continual living on the edge of death. They never mention it, but it is an obvious fact. What we have to do now over Germany in daylight means that if they come back some of their friends won’t.’

M

eanwhile, at the other end of the country is a very promising-sounding exhibition devoted to John Cecil Stephenson (1889–1965), an almost exact contemporary of Kennington, but an artist of quite a different kidney. Entitled Pioneer of Modernism, the show is at the DLI Museum and Durham Art Gallery until 29 April, and I hope to get up there to see it before it closes. I have in front of me the excellent catalogue, modestly priced at £5 and compiled by the exhibition’s curator, Conor Mullan, which has rekindled my enthusiasm for this little-known artist. Those readers who admired the Mondrian/Nicholson show at the Courtauld will be interested to learn that Stephenson was a neighbour of Mondrian when he lived briefly in Hampstead in 1939–40. When Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth evacuated themselves and their young family to Cornwall (and thus effectively founded the St Ives School), Mondrian stayed behind in Parkhill Road and saw quite a bit of Stephenson.

In those days Stephenson was painting rather beautiful geometric outline forms, superimposed and diagrammatic, in egg tempera on canvas. Many of his forms were upright with sloping tops, like the profiles of tall sails or pitched roofs. They have an optimism and even a serenity to them, helped by the choice of palette: predominantly greens and blues, with brighter accents. The work is planar and architectonic in feel, but strangely beautiful in its formality. Later Stephenson became more gestural and painterly in his abstraction, turning to oil paint as his favoured medium, but his tempera works of the 1930s have a greater lucidity and forcefulness. He remains one of the least-known English modernists, though this exhibition may help to change that.

Comments