No British soldiers will go to fight in Ukraine. The UK’s military involvement will be limited to weapons shipments and more forces to Nato’s eastern flank to try to deter further Russian revanchism. Despite this, domestic opinion in Britain — and other western countries — will be hugely significant in this conflict.

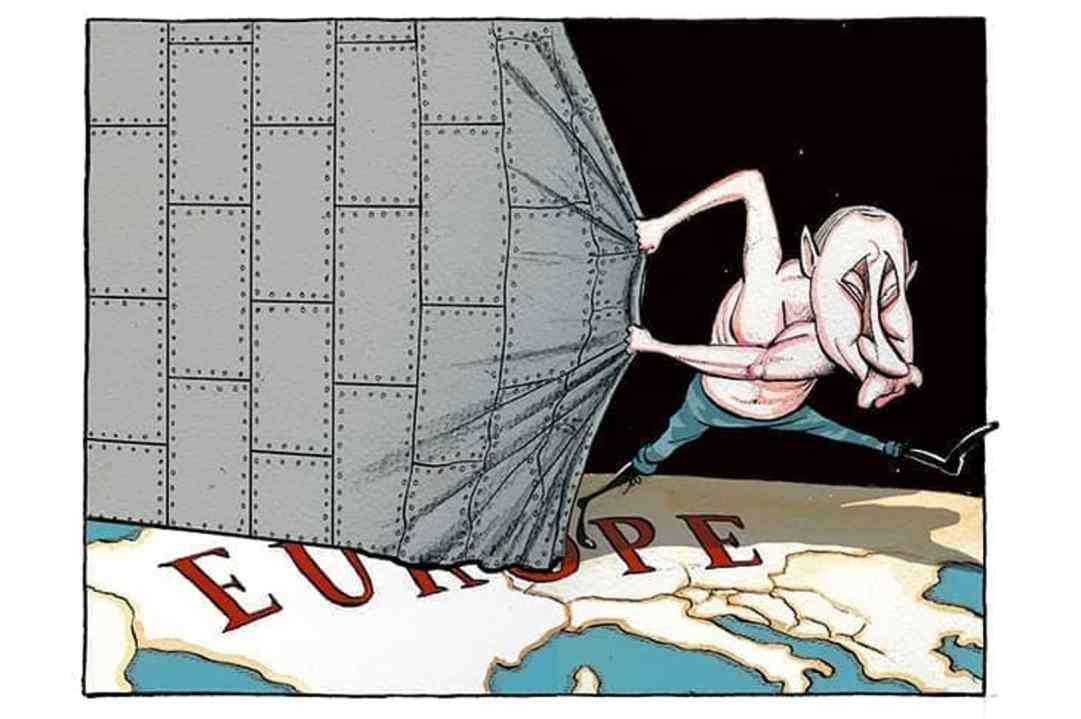

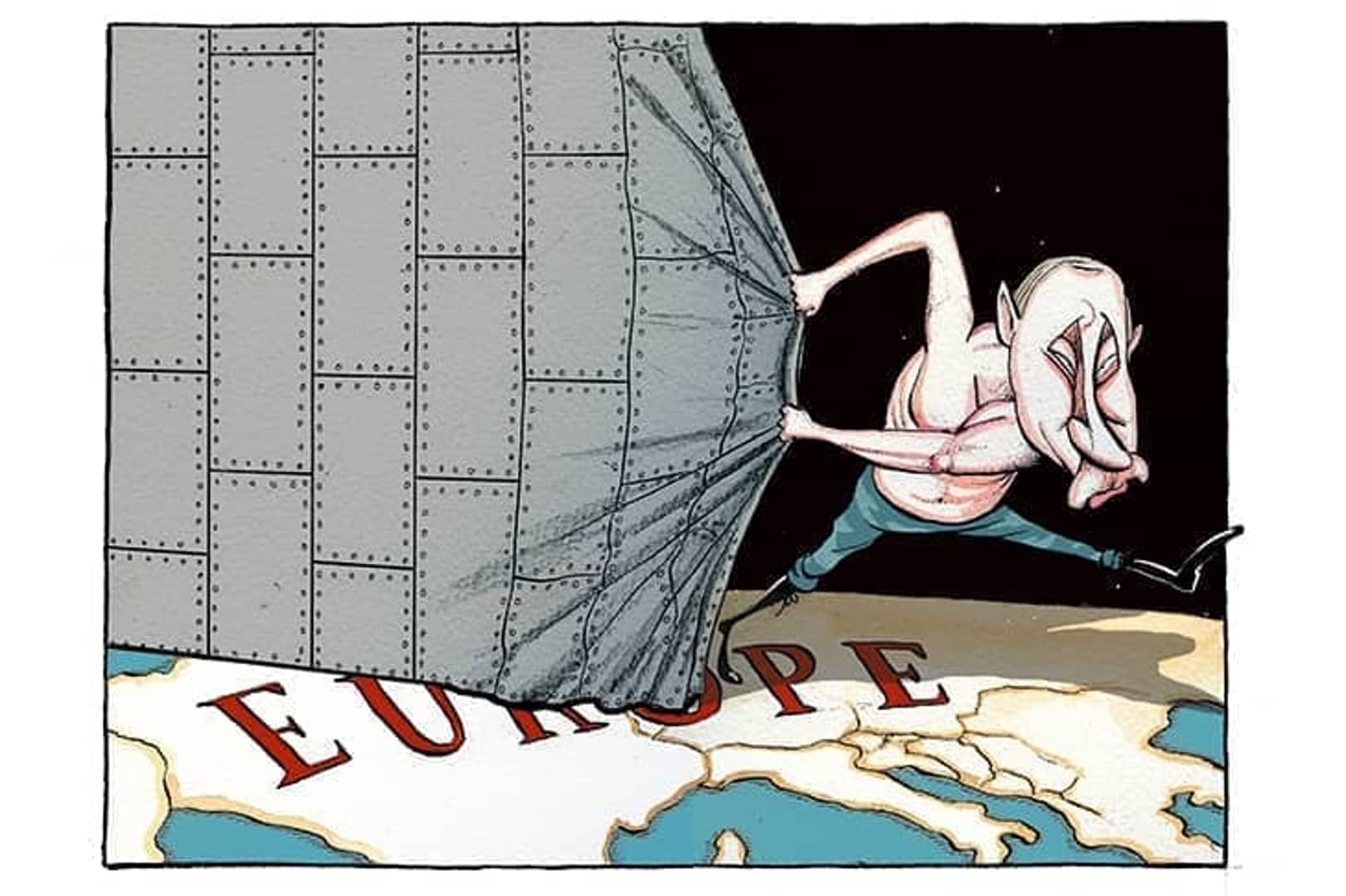

The West is trying to use sanctions to influence Vladimir Putin’s behaviour. However, there are clear limits to deterrence through economic measures, as Niall Ferguson writes in his article. The threat of sanctions was not enough to stop Putin unilaterally recognising the two breakaway republics in the Donbas, Donetsk and Luhansk, and agreeing to send troops there.

At the moment, Putin is convinced that he can weather whatever sanctions the West imposes. The British government’s initial measures will not have alarmed the Kremlin. Boris Johnson stresses that these are just the first tranche of the UK’s sanctions response. But it would have been better to start off with a much clearer statement of intent. With the exception of Germany’s welcome, if overdue, decision not to certify Nord Stream 2, the first set of transatlantic sanctions on Russia have been underwhelming.

Russia has been preparing to face expanded sanctions since the annexation of Crimea in 2014. It has built up foreign currency reserves of $630 billion, an increase of 75 per cent since 2015. It now has the fourth largest currency reserves in the world, despite being only the 11th largest economy. The reserves are akin to a third of the Russian economy. In a further attempt to bolster Moscow’s resilience against a western economic squeeze, Putin has kept state spending under control. The economic historian Adam Tooze calculates that Russia only needs oil to sell at $44 a barrel to balance its budget; Brent crude has spiked to $99 a barrel at the time of writing, in part because of the Ukraine crisis.

If the West is going to shake Putin’s confidence that he can ride out an economic response — something which might be difficult given how isolated he has become — the sanctions imposed will have to be sweeping. There is no way to do this without the West taking economic pain itself; it won’t just be the reputation launderers in the City of London who bear the brunt.

Politicians must be honest with the public about how sanctions will raise energy prices

Joe Biden has already started to prepare the American public for the fact that imposing sanctions on Russia will cost the US. In an address from the White House last week, he said he wouldn’t ‘pretend this will be painless’ and that energy prices could well rise. When Biden announced America’s first set of sanctions, he repeated his message that ‘defending freedom will have costs for us as well, here at home’. There are suggestions that the sanctions that are likely to come could increase the price of petrol at the pump in the States by as much as a sixth.

European leaders, including Johnson, have not sufficiently prepared their own electorates for the pain that sanctions could cause at home. In the Commons on Tuesday the Prime Minister did mention that the situation could push up energy prices, but he needs to speak to the public directly if support for these measures is going to be maintained in the long term.

Putin has picked his moment carefully: he is always more assertive when energy prices are high. Elevated energy prices not only boost the Russian economy but also make the West more vulnerable to spiralling costs and therefore less inclined to take measures that will exacerbate that problem. This is not an easy moment for democratic leaders to prepare their voters for bigger bills. Inflation in the UK is the highest it has been in 30 years; in the US it’s reached a 39-year high, and in the Eurozone it is at its worst since the creation of the currency bloc. This is already taking a toll on living standards. The biggest driver of inflation is energy prices. In the UK, petrol prices are 22 per cent higher than they were this time last year, and between December 2020 and December 2021 domestic gas prices went up 28 per cent and electricity prices 19 per cent. It won’t stop there, either, since the energy price cap will increase by 54 per cent in April.

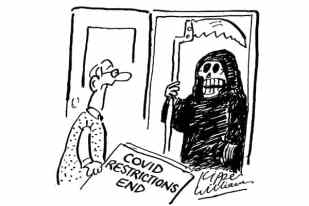

In these circumstances, it’s easy to see why politicians shy away from being explicit about how sanctions will raise energy prices. But they must be honest with the public about this. If they aren’t, Putin will calculate that the West doesn’t have the willpower to maintain strict sanctions for long and so the measures will be even less likely to deter him.

Another challenge Britain will face on the home front will be cyberattacks, which will be one of the ways that Moscow responds to sanctions. The National Cyber Security Centre has already warned British organisations to boost their defences. Moscow uses cyberattacks because they are deniable and exist in the grey zone of warfare which Putin’s Russia has made its speciality.

The view in Whitehall is that Russia will opt for actions that would fall short of the bar for a British counterstrike. Moscow will also be aware that ‘serious cyberattacks’ are one of the reasons for Nato to invoke Article 5, the alliance’s collective security guarantee. Critical national infrastructure, therefore, won’t be targeted. Russia and its criminal proxies will instead look for softer targets to cause disruption through hacking.

Ultimately, western leaders and their electorates need to accept that the Cold War peace dividend is over, and that defence spending will have to rise considerably. Putin simply does not accept the current balance of power on the continent and his regime will continue to be a security threat to the West for a long time. Europe’s holiday from history has come to an end.

Comments