David Mitchell’s fifth novel, an exotically situated romance of astounding vulgarity, has some things to be said for it.

David Mitchell’s fifth novel, an exotically situated romance of astounding vulgarity, has some things to be said for it. It will certainly entertain the simpler reader that lurks within all of us, the one that hungers for the chase and the mysterious Oriental maiden with a fascinating physical flaw, that enjoys the spurt of blood, thrills to the race against time and positively hankers after bald, inscrutable, mind-reading villains in blue silk robes; and to the reader who hardly cares how these things are put into prose.

It is undoubtedly an exciting book, but in any number of ways an unsophisticated one, with a technique that in some aspects borders on the rudimentary. In the past, I’ve greatly enjoyed and admired Mitchell’s books. This one seems exactly calculated to demonstrate his weaknesses as a writer, and the writerly temptations he too easily yields to.

His brilliant debut, Ghostwritten, and his third, justly admired, novel, Cloud Atlas, were both structurally innovative works about the end of the world. The characters, in sequences of shorter narratives, were linked together by remote and impressively random means, building to massive, somewhat inexplicable climaxes. In between came an ingenious thriller with a contemporary, Japanese setting, number9dream, almost universally regarded as a detailed homage to the great Japanese novelist, Haruki Murakami, behind which any idiosyncratic style of Mitchell’s own could hardly be discerned. In Cloud Atlas, each chapter was a pastiche of a different novelistic manner, some obviously and enjoyably tawdry, one an evident and abject imitation of Russell Hoban’s famous created language in that great classic, Riddley Walker.

Doubts surfaced about his subsequent novel, Black Swan Green, a first- person account of teenage life owing less to the way teenagers speak than to Sue Townsend’s Adrian Mole books. Despite his evident inventiveness in creating a novel’s structure, I wonder about his attachment to anything but the conventions of literary storytelling. Some of those conventions, as served up in The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet, are threadbare indeed.

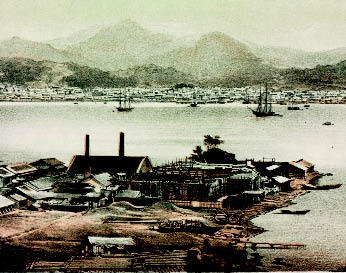

We are in 1799, in Japan. The nation, under the Shogun, is closed to the rest of the world. Some interest exists between the great, cryptic empire and the great European trading nations which are merrily carving up that half of the globe. Dutch traders are permitted to cast anchor at the port of Nagasaki, and to settle there. Not actually in Nagasaki itself: they dwell in the man-made island of Dejima. The ideas, cultures and science of the Dutch penetrate Japan, despite all precautions — including Christianity, against which strong measures are supposedly in place.

Jacob de Zoet is an immensely upright, somewhat priggish young man who has come to make his fortune and to learn the ways of the world. He has left a fiancée behind, and has brought eight boxes of mercury to sell at a profit. His fellow Dutchmen, he finds, are prone to corruption on a gigantic scale, and when he tries to act against one important figure he had previously regarded as honest, it brings about his downfall. He is also terribly in love with a Japanese woman with a damaged face, Orito Aibagawa. She has learnt midwifery from a Dutch doctor, Marinus; in a series of catastrophes, before she can reciprocate Jacob’s instant passion, she is spirited away to an abusive nunnery by a decidedly Fu Manchu-ish villain, Abbot Enomoto. Will she ever be rescued by Jacob from sex slavery and enforced opium addiction? Or will Uzaemon, the man forbidden to marry her, break from his constraining family and get there first?

You will, of course, have guessed by now that this tale is told in the present tense. All historical novels nowadays seem to be so written. There is probably an EU directive about it. Some novelist once told another novelist that they could make their writing more vivid that way, and everyone fell for it. The result is this sort of thing:

Dinner is a festive occasion compared to breakfast. After a brief blessing, housekeeper Satsuki and the sisters eat tofu in tempura batter, fried with garlic and rolled in sesame; pickled eggplant; pilchards and white rice. Even the haughtiest sisters remember their commoners’ origins when such a fine daily diet could only be dreamt of, and they relish each morsel.

I’m afraid that any author prepared to write, without irony, ‘relish each morsel’ is not going to be turned into a vivid one by a shift of tense alone. Where did this widespread habit come from? I’m guessing, in part, from the conventional narrative style of screenplays. Perhaps there are other signs here of a longing for the big Hollywood movie, and the novel is prepared to meet the agents halfway.

In the same category falls Mitchell’s atrociously Dan-Brownish habit of rendering style indirect libre and characters’ thoughts in italics. Certainly Mitchell’s narrative resources here are dismayingly thin, and overwhelmingly limited to the two things that film does naturally — dialogue and an observation of something moving. The full range of novelistic possibilities is hardly even envisaged, and what Mitchell is prepared to do is often placed in awkward juxtaposition. Obsessively, and with unnaturally mannered effect, a line of dialogue is interrupted with small-scale, trivial action, or stage directions:

‘I’ll keep yer breakfast’, Grote chops off the pheasant’s feet, ‘good an’ proper.’

‘Here boy!’ whispers Oost to an invisible dog. ‘Sit, boy! Up, boy!’

‘Just a slip o’coffee,’ Baert proffers the bowl, ‘to fortify yer, like?’

‘I don’t think I’d care,’ Jacob stands to go, ‘for its adulterants.’

What, really, does Mitchell’s technique allow him to do? In recent days, he has spoken in an interview of his invention, in this novel, of a ‘thought-spike helmet’:

I imagined there was a helmet mounted on the head of one character per chapter. The helmet has a spike in it that can go into that person’s head and read that one person’s thoughts, but nobody else’s.

Is it not rather alarming to find a novelist of Mitchell’s experience describing, as if it were his own personal discovery, an utterly conventional treatment of point-of-view that has been around for at least a century?

Actually, although the texture of the writing is exhaustingly thin, I must admit to quite enjoying the incredibly corny aspects of the traditional historical novel, as served up here, with the central-casting yokels talking historical-novel filth like nothing on earth:

This princeling’s gherkin was so rotted it glowed green; one course o’ Dutch pox-powder an’ Praise the Lord, he’s cured!

And I rather liked the traditional periodic recourse to some really repulsively over-researched bit of bloodletting to keep the local colour up — a difficult birth, a double beheading, a gallstone removal without anaesthetic:

[Marinus] takes out the stone, retrieves his finger from Gerritszoon’s anus and wipes both on his apron.

I even quite liked the hilariously inscrutable Orient scenes: De Zoet falling in love with Orito at once in a garden (‘For a priceless coin of time, their hands are linked’); characters saying, in all seriousness, ‘Japanese custom is different to Dutch’; even a kindly old crone, wise in the ways of herbs, living alone on a mountainside in the usual mountain hut.

But there seems not much doubt that Mitchell, always a playful author, has become in some respects an unserious one, no longer trying to observe freshly before he writes. Those habits of observation are the novelist’s fundamental duty.

Comments