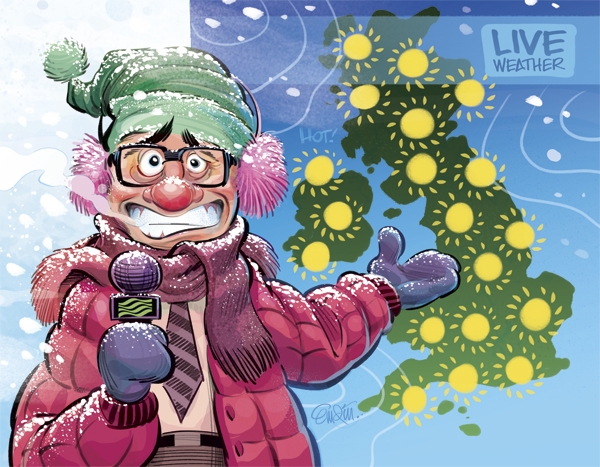

It has been a glorious sunny week in Britain — it feels as if summer is finally here. As Andy Murray was winning Wimbledon, temperatures on Centre Court exceeded 40˚C in the sun. Northern Ireland has been hotter than Cancun. The papers have begun their annual drip-feed of stories about ‘tombstoning’ — young people throwing themselves from cliffs and bridges into water. It is hard to believe that it was just a few weeks ago that the Met Office braced us for a ‘colder-than-average’ July and a decade of soggy summers. Not so hard to believe that they held a crisis meeting recently, to discuss why they have got the weather so wrong for so long.

Only this week has Britain had a small taste of the kind of temperatures the Met Office has been promising for over a decade. In September 2008, it forecast a trend of mild winters: the following winter turned out to be the coldest for a decade. Then its notorious promise of a ‘barbecue summer’ was followed by unrelenting rain. Last year, it forecast a ‘drier than average’ spring — before another historic deluge that was accompanied by the coldest temperatures for 50 years. Never has the Met Office had more scientists and computing power at its disposal — yet never has it seemed so baffled by the British weather.

But there is no paradox. It is precisely the power of this technology in harnessing climate scientists’ assumptions about global warming that has scuppered the Met Office’s predictions — and made it a propagandist for global warming alarmism. It has become an accomplice to a climate change agenda that now affects where and how we travel, the way houses are built, the lights we read by. And its errors are no laughing matter to tourism industry chiefs in Cornwall and the north-west, who say the Met Office’s false warnings of dire summers cost hundreds of millions of pounds in cancelled bookings.

For some time, the Met Office’s longer range forecasts have served a political purpose. They tend to be issued just before the United Nations annual end-is-nigh summit in November, so they can have a powerful impact if they are sufficiently scary. But for 12 of the last 13 years, the Met’s temperature forecast has been too high. As Warren Buffett likes to say, forecasts tell you little about the future and a lot about the forecaster. Recently, the Met Office has decided that global warming means colder summers in Britain (due to North Atlantic sea temperatures pushing the jet stream south). But they may have to readjust their forecasts again.

With this record, if the Met Office were a secondary school, it would be subject to special measures and intensive monitoring. Instead its directors shower praise on themselves. ‘Our successes during the past year form a strong base from which we can go forward,’ they write in their annual report. Say it often enough, and people will believe you. In the recent spending announcement, the Treasury rewarded the Met Office with a new supercomputer so it can develop ‘its world-class research base’. Being so wrong so often is a costly business.

The Met Office doesn’t need a new computer. It needs a new computer model and updated assumptions to replace its HadCM3 model, which builds in an average warming of 0.2˚C a decade in response to rising greenhouse gases. Although emissions have been higher than expected, global temperatures have been flat for 15 years. The Met Office’s own temperature series even shows a small decline since 2006.

In an interview last month in Der Spiegel, the German climate scientist Hans von Storch — a rare exception to climate science’s cult of omertà — admitted that in model simulations, a 15-year pause occurred less than 2 per cent of the time and a 20-year pause not at all. If the current standstill continues for another five years, he said, ‘We will need to acknowledge that something is fundamentally wrong with our climate models.’ Perhaps that is why, at a February conference on avoiding dangerous climate change, Dr Julia Slingo, the evangelical chief scientist of the Met Office, warned of the ‘urgent need’ to shift discussion away from the average global temperature and instead focus on changes in rainfall and weather patterns.

The Met Office has a lot to lose in terms of its reputation. Britain is something of a global leader, second only to America in providing the most authors and review editors to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), whose periodic reports are seen as the bible of global climate change. Of those from Britain, nearly a quarter work for the Met Office. ‘I have Julia Slingo on speed dial,’ Sir John Beddington quipped towards the end of his tenure as the government’s chief scientific adviser.

When making their case, climate experts indulge in the widely shared misapprehension that scientists are much more intelligent than non-scientists. So when in 2010 Dr Slingo appeared before the House of Commons Science and Technology committee to talk about the Met Office’s take on the Climategate emails, she treated MPs like patsies.

At issue was the discredited ‘Hockey Stick’, a temperature series that purportedly showed static temperatures for 900 years and a sharp increase in the 20th century. Dr Slingo told MPs that the relevant chapter in the IPCC report had been subject to the ‘most robust peer review process’ seen in any area of science.

Had the Met Office been worried that the peer review had failed? ‘Not at all, no,’ Dr Slingo replied. Anyone with the briefest acquaintance with the facts would know that this was a fairytale — yet the only MP to vote against the committee’s rubber stamping of the science was Labour’s Graham Stringer, an analytical chemist by training.

Thanks to the Climategate emails, we know that in private, climate scientists saw things very differently. At the very least, one of them wrote, the Hockey Stick was ‘a very sloppy piece of work’. In this respect, there is more integrity in the NHS than in British climate science. Bound and gagged though they may be, at least there are whistleblowers in the NHS.

Worse was to come. Last November, the Labour peer Lord Donoughue tabled a written question asking whether the government considered the 0.8˚C rise in the average global temperature since 1880 to be ‘statistically significant’. Yes, came the reply. Douglas J. Keenan, a mathematician and former quant trader for Morgan Stanley, knew the answer was false. With Keenan’s help, Donoughue tabled a follow-up question. The Met Office refused to answer it, not once, but five times. Its refusal to clarify its stance left the energy minister, Baroness Verma, in an awkward position. Only then did it confirm that it had no basis for the claim.

The Met Office’s record of obstruction and denial should give pause to even the firmest believer in global warming and illustrates the profound incompatibility of state science (which climate science has become) and the real thing. ‘We should listen to the scientists — and we should believe them,’ said Ed Davey, the Climate Secretary, earlier this year. Yet his department has officially sanctioned the anti-scientific practice of withholding data. The climate secretary has denounced sceptics and other non-believers as ‘crackpots’ — an attack conforming to a key feature of what the philosopher Karl Popper defined as pseudoscience. Genuine science invites refutation; pseudoscience tries to silence dissent.

Scepticism in science should always be welcomed. With climate science, it is necessary. As Davey remarked in his speech, ‘the science drives the policy’, but last month might well mark the moment when the government’s energy policy lost all contact with reason. It doesn’t take much to imagine how Mrs Thatcher would have galvanised her government if she had been told Britain was sitting on the richest shale gas deposits in the world. Yet the Cameron government pushes on with the Energy Bill to implement the 2008 Climate Change Act and its colossal £404 billion price tag.

Last month saw Ofgem warn of power rationing; the government agree a price guarantee for nuclear power; and in effect a £10 billion transfer from British to French taxpayers via state-owned EDF. In Brussels, Ed Davey told the EU to adopt unilateral emissions cuts, despite the fact that even Germany is having second thoughts about this strange form of economic suicide.

None of this would be happening without climate scientists — led by those at the top of the Met Office — raising the alarm and behaving like propagandists. ‘We seem to be losing the communications battle,’ Dr Slingo told the conference on dangerous climate change in February. Winning the battle meant personalising the narrative about what climate change might mean in the future, she said. This is not science. It is political spin from the same playbook that brought us Tony Blair’s ‘dodgy dossier’ on Iraq. It comes as no surprise that the Met Office retains PR consultants to help with its climate change message.

At the very least, the Met Office has a duty of care to the rest of us: to be balanced and objective, to admit when they’ve got it wrong, not to indulge in speculation and to tell us what they don’t know. The Met Office has not discharged that duty. Politicians, in the grip of a mania, have told us we must defer to scientists.

But Britain is in this mess because scientists became political cheerleaders. In doing so, they abandoned science as the disinterested pursuit of knowledge. Failure to predict the weather is, in the scale of things, the least of it. With the cost of climate change policies approaching half a trillion pounds, the Met Office is setting itself up for the largest case of public misfeasance in British history.

Comments