We know of the Durrells mainly through their own writings, outstandingly My Family and Other Animals, about their years in Corfu in the 1930s, and from the image of them created by TV and film adaptations of this work. Gerald and Lawrence were the best known members of the family, the first as a zoologist and conservationist, the second as an experimental writer. Their siblings, Margaret (Margo) and Leslie, will always be perceived through the lens Gerald turned on them in My Family – the former as a flighty eccentric, something like an extra from a Carry On film, the latter as a pantomime villain. Their mother, Louisa, was loved unreservedly by her children and comes across in My Family as a kindly eccentric. In truth, she hovered over them for much of their lives, adored but not properly understood, mainly because she was a lifelong alcoholic.

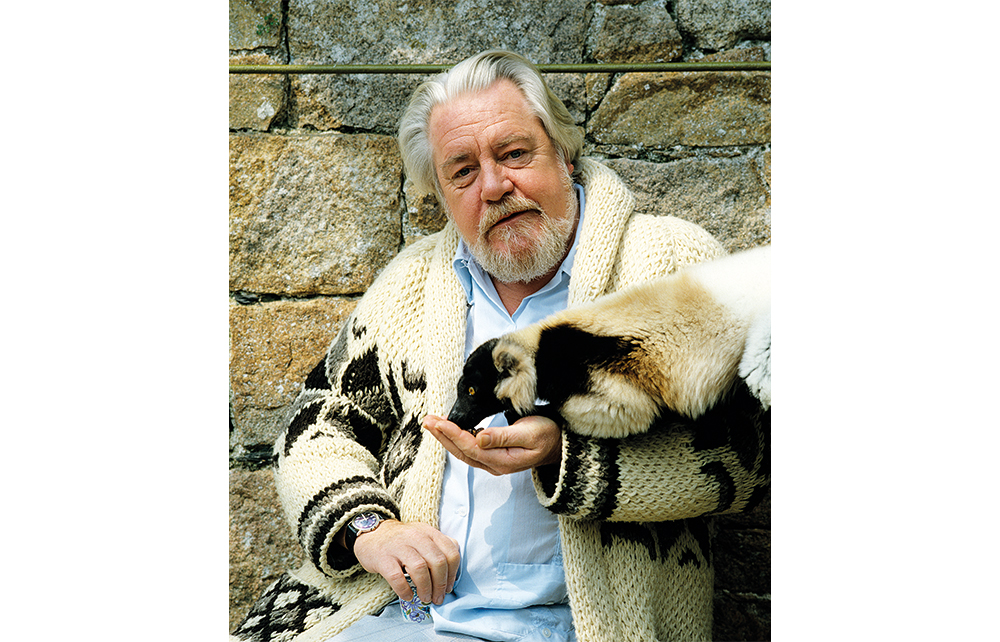

Obsessed with animals, Durrell became in middle age someone who loathed his own species

After Corfu, Gerald began keeping stray animals in the family house and garden in Bournemouth. He worked for a while at Whipsnade Zoo and at the end of the 1940s, making use of a generous legacy from his father, started bringing creatures in danger of extinction to England, initially from Africa. After failing to gain permission from various councils in southern England to found a zoo, he leased Les Augrès Manor and its grounds on Jersey, which endures as a monument to his ideals. For one thing, he revolutionised the notion of the zoo, transforming it from a source of prurient entertainment to a means of preserving threatened species.

Myself and Other Animals comes out under Gerald’s name but is edited by his widow Lee, his second wife; and while it is presented as his unpublished autobiography, albeit mainly by implication, it is anything but. It includes some passages from the material archived in Jersey that amount to notes for his memoir; but most of it is made up of extracts from published work, distributed chronologically. It is a strange case of hide and seek. Jacquie, his first wife, crops up only briefly. Without her, My Family would not have been written; but here she is something of a ghost, present but almost immaterial, which – no doubt involuntarily – reflects what happened when they split up. Gerald tried to erase her from all records of their shared achievements as environmentalists, rather like Stalin’s policy of removing unsuitable figures from photographs of the Soviet hierarchy.

The Princess Royal writes a foreword, and obviously she admired Gerald because she allows the inclusion of the story of her visit to Les Augrès when he introduced her to Frisky, a mandrill, and asked if she would like to ‘have a behind like that.’ ‘No,’ she replied decisively, ‘I don’t think I would.’ Apparently the flicker of a smile crossed her face and two weeks later she became patron of the Trust.

The parts left out from the Jersey archive are not scandalous, in that they do not contain confessions of sexual activity or anything otherwise shameful. What they show is the real Gerald. My Family and Other Animals (1956) sold more than 300,000 copies in its first year and has never been out of print. It is supposed to be a documentary account of the Durrells in Corfu but is largely lies and fantasies.

Why did Gerald do this? The answer might be found in the unpublished notes for his memoir where he expresses unreserved contempt for writing – an activity he is obliged to undertake to pay for his animal-focused mission. Most of all, he does not like writing about people; compared to animals, he felt they did not deserve the effort. Consequently, he transformed the thwarted expectations of Corfu into a carefree pantomime. In their light-hearted spontaneity, the characters of the book do indeed resemble ‘other animals’.

This book is a moving tribute to Gerald’s endeavours and achievements as a conservationist; but what is evident in the notes largely omitted is what motivated his concern for, indeed obsession with, animals. From a young man determined to protect vulnerable species, he became in middle age someone who loathed the species of which he was a member. In the draft memoir, the natural world is his most comfortable environment, and it is clear he preferred the company of those who are part of it – insects, birds or fish – to the company of those he contended had intruded upon it.

The notes reveal a depressive whose affection for animals and the natural world reflected his unease with the human condition, and this eventually ruined his first marriage. Jacquie was just a little too human. In his sixties, Gerald treated the universe of non-humans with what amounted to envy: he wished he were more like them than the way he was.

Comments