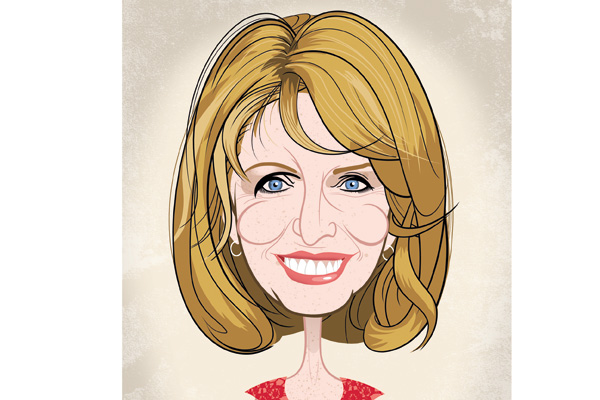

Here comes Jane Asher. She swings through the doors of a small Chelsea hotel, chucks her bag on the floor, and sits down with an expectant look. Her voluminous red hair has attractive hints of something blonder on top. Her eyes are pale blue, and extraordinarily intense, and she has a fulsome rack of plump white teeth that hint at large appetites. But her figure is as trim as a teenager’s.

We meet a few weeks before she begins rehearsing Charley’s Aunt, the classic Victorian farce in which she plays a Brazilian dowager, Donna Lucia d’Alvadorez.

Does she think it’ll be more fun because the script is a bundle of laughs?

‘No, there are always those technical things that are just as tricky to do. And if it’s not funny, it’d be a disaster. Whether it’s comedy or tragedy, the fear is the same.’ She seems fascinated by the subject of backstage nerves. ‘First nights are terrifying,’ she says. ‘Agony. Awful, and the fear never really gets any better. The first preview has a sort of terror of its own. It’s very, very scary because there are people watching for the first time. And then press night inevitably is bad as well. You shouldn’t mind, but you can’t help it.’

All actors claim not to read reviews but Asher is the first I’ve believed. ‘I genuinely don’t read them,’ she says, ‘for two or three years.’ Her priority is to protect her performance from external influences. ‘If a critic says, “She delivers this line and it’s just fantastic,” then you come to that line and you think, “Huhhhhh, this is where I’m just fantastic.” But I don’t know how I did it. What did I do? And anyway, one critic can think that something’s great and another thinks it’s crap, so you know…’

Sam Mendes once said that there’s no such thing as the history of British theatre, only the history of British press nights.

‘Oh, exactly. That’s true. I often think critics must see these strange productions where everybody’s slightly hyper. They never see a normal show where people are relaxed and enjoying it.’

And what does she do after the critics have gone? ‘Get drunk!’ she says, and then performs a swift U-turn. ‘That’s putting it crudely. You have a few drinks and tell everyone how wonderful they were. It’s the relief of it.’

She was talent-spotted as a child while trotting through Fitzrovia hand-in-hand with her mum. Her red hair caught the eye of a passing producer. When he asked her to take a role in a film, her parents agreed, ‘because it might be fun’. More child parts followed. And the offers kept coming in as she moved into adulthood so she never needed to train.

Has she thought about directing? ‘It’d be nice to be the manipulator instead of the plasticine,’ she says bluntly. But her creative urges have taken her elsewhere. Into the patisserie. She’s written several bestsellers about decorative cake-making and she runs an internet business supplying materials for the domestic market. ‘We sell all the sugar craft stuff that you need to make the cakes at home. There’s a huge catalogue of online stuff. I mean serious cake decorators, you’d be amazed at the equipment and the supplies that you need if you’re seriously into it.’

Since we’re having afternoon tea, I ask her to assess the sugar-dusted swirls of suntanned dough sitting before us on a tissued saucer. She picks one up and has a taste. ‘All right, not great, hurh, hurh,’ she says with a nervous laugh.

If acting hadn’t beckoned, she says she might have pursued a career in science. Her father, Richard Asher, was a renowned endocrinologist. ‘His biggest claim to fame was that he named Münchausen syndrome.’ Why didn’t he enter medicine’s pantheon of immortals and christen it after himself? ‘Well, exactly. Typical of him. Very self-effacing. And very witty, too. He named it after Baron von Münchausen because he told all those fantastic stories.’

When not working, she describes herself as ‘butt-lazy’. And she can’t find an answer to the question, ‘What do you do in your spare time?’ ‘I’m always sort of busy. But if you pin me down, what do I do?’ she says with her eyes wandering. ‘I mean, I write as well, so, yeah. I’ve written three novels. And I suppose about 16 other books, more or less, something like that. But I’m not doing one at the moment. I should but I’m not. I write when I’ve got time.’ Nineteen books. Clearly, a busy person’s idea of butt-lazy.

We turn to politics and she enthuses about exercising her democratic rights. ‘Particularly as a woman. The fact that those poor ladies chained themselves to railings and ran under horses’ hooves. I get very upset if people don’t bother to vote. If you read about other countries where you have no power, no voice, it’s so easy to take it for granted. And nasty things can come out of the woodwork so quickly.’

Is she following the Euro crisis? ‘I can’t begin to understand what’s going on. It just seems bizarre, the amount of money involved. If you look at the American debt, the sums are unimaginable.’ She then refers rather vaguely to an economics piece she heard that morning on the radio. ‘I gather they’re going to do anything to save the euro. And the European Stability Fund, which I hadn’t heard about before, is going to buy up the Greek, Spanish and Italian debt, and they’ll be able to use that debt as collateral to get money from the Central European Bank. So it makes this nice little virtuous circle. And it sounds like, “Oh, you know that’s magic. Let’s do it.” But I mean the collateral on those debts, you wouldn’t think, would be worth anything at all. So there’s all this weird financial stuff that goes on in the banking sector. It’s completely out of our hands. Out of our control. And I know no more than any other normal person.’

Perhaps a bit more than ‘any other normal person’. The one subject she won’t be drawn on is the 1960s. She was Paul McCartney’s girlfriend and they were engaged briefly. ‘I made a decision many, many years ago that if you’re going to have any vaguely happy relationships, you don’t talk about it. And I never have.’

She then drops a broad hint that her lifetime’s silence might be broken easily enough.

‘When we’re sitting with a glass of wine, not doing an interview, we’ll discuss all that. In depth!’

Comments