No need to explain why we’ve disinterred this piece by Peter Ackroyd, on the last

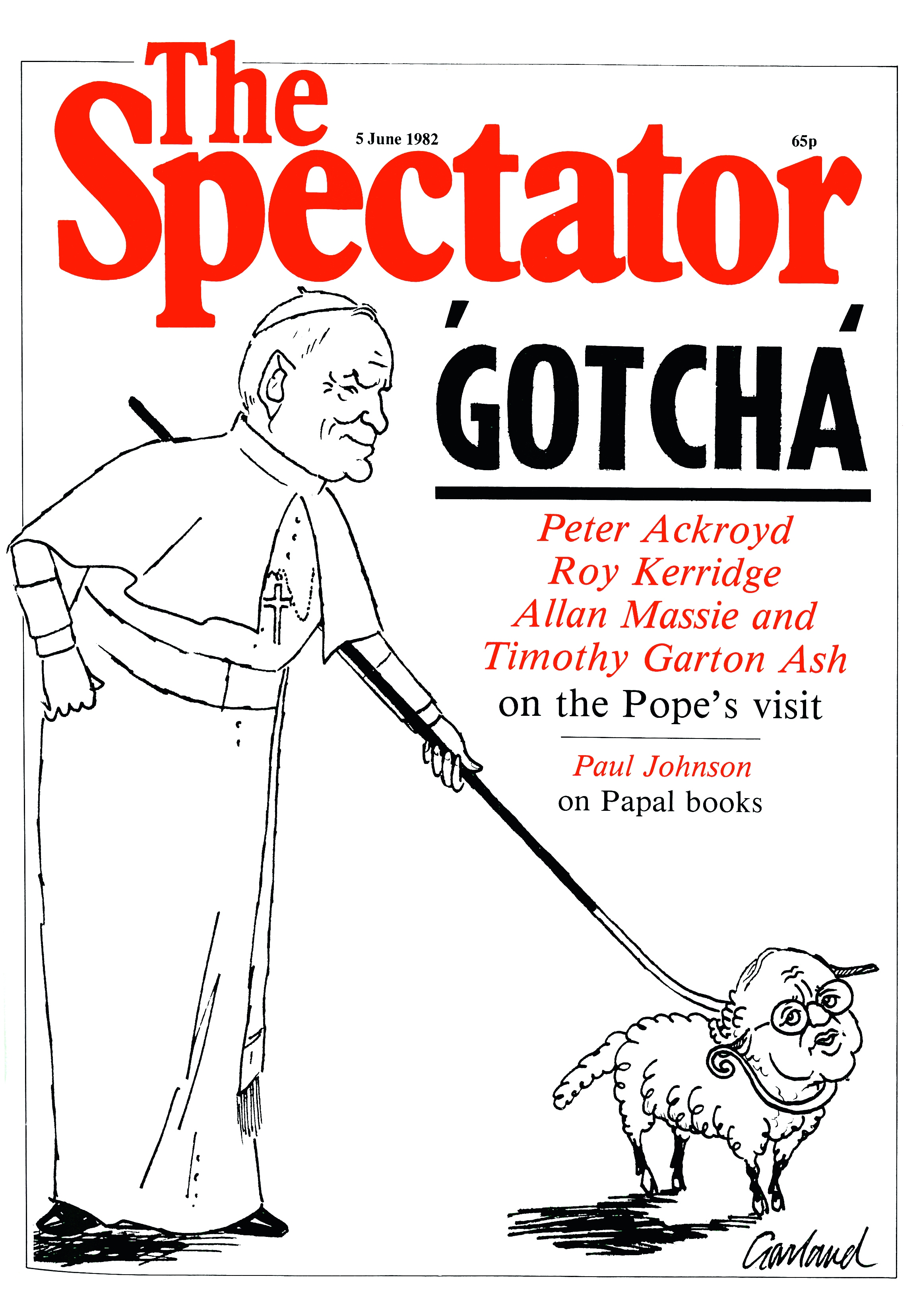

papal visit to Britain, from the Spectator archives. And, to the left, the cover image by Garland from that week’s issue. As news emerges that five people have been arrested in connection with a terror plot against Benedict XVI, a reminder that papal visits are always replete with global-political

significance:

No need to explain why we’ve disinterred this piece by Peter Ackroyd, on the last

papal visit to Britain, from the Spectator archives. And, to the left, the cover image by Garland from that week’s issue. As news emerges that five people have been arrested in connection with a terror plot against Benedict XVI, a reminder that papal visits are always replete with global-political

significance:

The Pope and his princeling, by Peter Ackroyd, The Spectator, 5 June 1982

The pilgrims arrived in Canterbury, carrying their fold-up chairs in plastic Sainsbury bags; strange rumours on the train from London: ‘You can’t get into town without a permit. They say they’ve stopped all the cars for three miles … They’ve taken the door off the cathedral’. ‘They’ hadn’t, in fact, but it was encased in scaffolding as if in danger of crumbling. Inside, the primarily Anglican congregation settle down in anticipation: lots of waves and smiles, clergymen clutching their tickets with that benign, slightly silly, expression which clergymen always seem to have.

When I was a boy, we entered the church with a certain atavistic awe as if we were going into an echo chamber of strange rituals and sorrowful renunciations. I can still recall the silence when the monstrance was shown to the people, and we were forbidden to look at it. We would sing hymns like ‘Faith of our father, holy faith, we will be true to thee till death’ – and then there was something about ‘prisons dark’ and flames. But that is the faith the Pope leads – here, in Canterbury Cathedral, the atmosphere was mild and comfortable, exuding the sort of muted satisfaction which one might find at a flower show.

But then the Pope arrived. They greeted him, with fanfares of trumpets and loud applause, like a returning king. It was described in the newspapers as ‘moving’ but it was more odd than anything else; the enthusiasm seemed out of place and somewhat extravagant – like the sound of applause in an English cathedral, like the scarlet of the cardinal’s robes and the Pope’s cape which seemed almost pagan beside the sombre greets and blacks of the Anglican clergymen. (There is a passage in Nathaniel Hawthorne about scarlet as the colour of blood and desire.) It was a highly theatrical occasion.

The papacy itself is the supreme emblem of religion as theatre, and there is no doubt that the present Pope fills his role to great effect – the impassive countenance, the deliberate economy of his gestures, the way his voice rises in blessing or in denunciation; when the Archbishop of Canterbury mentioned Poland, he tilted his chin upwards and gazed sombrely at the vaulted roof. Beside him Archbishop Runcie seemed a plaintive and whimsical figure, with a tremulous voice – the voice of the mad aunt who is allowed downstairs at tea-time.

One had only to witness the scenes at Southwark Cathedral to recognise the extraordinary power of the Pope. The sick and the dying stretched out their arms to clutch at him, and they wept when he anointed them with holy oil. It is a primitive faith, perhaps – the ‘laying on of hands’ is an archaic ritual quite un-Christian in origin – but it is a mark of the significance of this man that he can still embody such faith. It is a matter of semantics only whether you describe his power a ‘spiritual’ or ‘political’, since we are dealing here with responses which reach beyond that division; and, more importantly, it is not distinction which the Church, or the Pope, can in fact acknowledge. When the crowds wave their banners and shout ‘We Love You’, they are paying homage to a man who enunciates principles which must have a marked effect in the temporal sphere and whose purpose is to affect the disputes and procedures of the political world. When he travels to Argentina, he will no doubt speak of the dangers of communism and the perils of too close a relationship with the Soviet Union – is that a political, or a spiritual, stance? The question is meaningless.

When Pope John Paul describes his journey to England as a ‘pastoral visit’, he means quite simply a visit to the people. His is an unashamedly populist stance – he is addressing the people over the heads of their ruler, and reminding them of the principles and perceptions which may be at direct variance to the professed aims of those rulers. In his first minutes in England he called for ‘peace’ in the South Atlantic and , in Coventry on Sunday, he castigated those who use war as a method of resolving international disputes. It may be couched in the language of eternity but the message is a quite specific one – that the British Government has erred in a fundamental way, that it has abrogated those values which people come to in their thousands to head him confirm. It might be called an ‘interference’ in the affairs of government expect that the Pope feels himself obliged to interfere in such a manner:

‘To condemn kings, not serve among their servants,

Is my open office.’

These are the words of Thomas Becket, from Murder in the Cathedral, a man of authority who stood out against the State and who sought a martyr’s death: perhaps it was fitting that it should be at Becket’s shrine that the Pope prayed on Saturday.

Just as it is misleading to separate the ‘political’ from the ‘spiritual’ role of the Pope, so it is wrong to divorce the ‘pastoral’ and the ‘ecumenical’ aspects of his visit. They are part of the same mission. The Pope is claimed to be, after all, Christ’s Vicar on earth,’ and so by definition he is the pastor of all peoples, whether they choose to recognise the fact or not. His ‘flock’ cannot be limited to the Catholic community – he is God’s representative and God has no constituency. So it was that, in his Canterbury sermon, he declared that he brought to the Anglican community ‘the good will of all who are united with the Church of Rome, which from earliest times was said to “preside in love”‘. He could not have made it plainer: he had come to reclaim his own.

It was deeply unfortunate, then, that the present Archbishop of Canterbury should seem so palpably the smaller figure, a princeling who has erred but who may by a mixture of toughness and, for him, face-saving diplomacy be allowed to return to the fold and bring England, ‘the dowry of Mary’ back with him. If the Anglican church decides to move towards ‘unity’, the tenets of its faith are not so strongly held or clearly defined that they can withstand the moral authority of such a man as the Pope or the faith which he has used both as a shield and a weapon against those who doubt the Catholic Church’s role.

But there is something else to be said. Although the Pope and his Church deny any real separation between spiritual and political affairs, there is no doubt that we all live as though one existed. It was perhaps fortunate that the Pope arrived during the was in the Falklands; that crisis, and the attendant emotions which it has elicited in the country, have demonstrated as nothing else could, the limits of the Pope’s actual authority – the boundaries, if you like, of his spiritual appeal. In confrontation with the undoubted nationalistic convictions and fervour which this dispute had evoked, his power fades – and it fades in precisely that area where, by contrast, the Anglican faith grows stronger. Archbishop Runcie, after all, supported the sending of the task force, and in doing so he confirmed the role of the Anglican church as the spiritual arm of the State. A vulgar but not inapposite analogy might be made between the Pope and the EEC. The Anglican Church’s identity is essentially the identity of the nation – the country’s interests are also its interest. Only if we were to lose, or neglect, that identity and those interests would the Pope’s compelling message also seem to be a compulsory one.

Comments